You could argue that Emile Smith Rowe’s goal did not stand out in last weekend’s wider collection of finishes.

Fulham ran out 2-1 winners against Nottingham Forest, with their opener coming from a well-worked sequence that saw Adama Traore cut inside onto his left foot before delivering a delightful ball for the onrushing Smith Rowe to head home.

What did stand out was that a very similar opening goal was scored by Arsenal just a few hours earlier on that Saturday afternoon.

Mikel Merino found space between two Leicester defenders and rose to nod in Ethan Nwaneri’s inswinging cross to the far post. Against a stubborn defensive block, it was the perfect method to break the deadlock with just 10 minutes to go.

What stood out even more was how this type of goal was rather typical of the past couple of seasons. As rudimentary evidence of this, there were 143 open-play headed goals in the Premier League in 2023-24 — comfortably the highest of the previous five full campaigns. This season is on the path to matching that figure.

Advertisement

Tactically, teams have become increasingly protective of the central channel of the pitch — often condensing the space in this area and forcing their opponent to go around them during build-up and attacking phases.

Naturally, this means teams are asked to create from wider areas before funnelling the ball back towards the goal when they enter the attacking third.

The consequence? That’s right, it looks like crossing is back on the menu in the Premier League.

First, a quick history lesson.

It is worth highlighting just how much open-play crossing has fallen when tracing back to 2006-07 — an era of “peak Barclays” where the order of the day for any wide player was to get the ball out of your feet and stick it in the mixer.

For context, last season’s average of 12 open-play crosses per team, per game was a 26 per cent decrease in the average tally accrued per game nearly 20 years earlier. Statistically, this makes sense given that crossing is regarded as a low-probability — even counter-productive — way to score a goal compared with other methods of attack.

Football evolves, but it can also go in cycles. Looking at the graphic below, the slide in open-play crossing is clear — but this season’s figures suggest that the slide is not just slowing, but starting to trend in the other direction.

Of course, there is nuance when considering the different types of crosses made in open play.

The Athletic previously provided an analysis to separate the half-space dinks from the whipped touchline deliveries. But, for this exercise, we can bucket cross types into broader themes.

Using Fulham and Arsenal’s examples above, the back-post cross appears to be back in fashion this season as teams look to overload a specific area in a repeatable manner.

The cross itself can come in different forms — be it a driven, low ball to the opposite winger or a lofted ball for a centre-forward to attack — but the rate of chances created via such means is higher than ever this season.

Advertisement

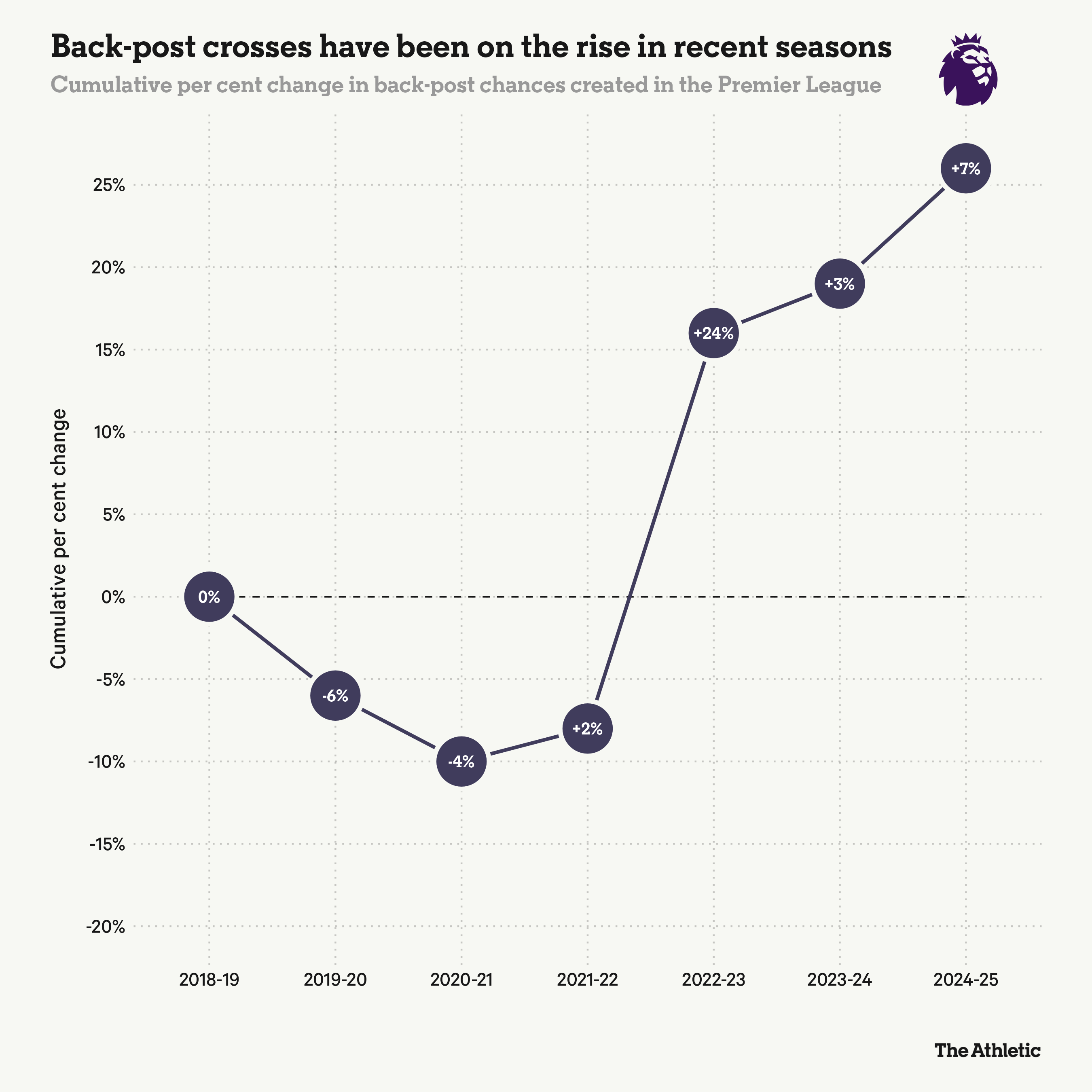

This is best shown by looking at the cumulative per cent change in back-post chances per game since 2018-19 — allowing us to better understand the rate of increase and decrease of such cross types season-on-season.

What is notable in the graphic below is the spiked 24 per cent increase in 2022-23 — a year when a certain Erling Haaland arrived in the Premier League. There has been a steady rise since then, but the cumulative rise of 26 per cent more back-post chances created per game this season compared with 2018-19 certainly passes the eye test.

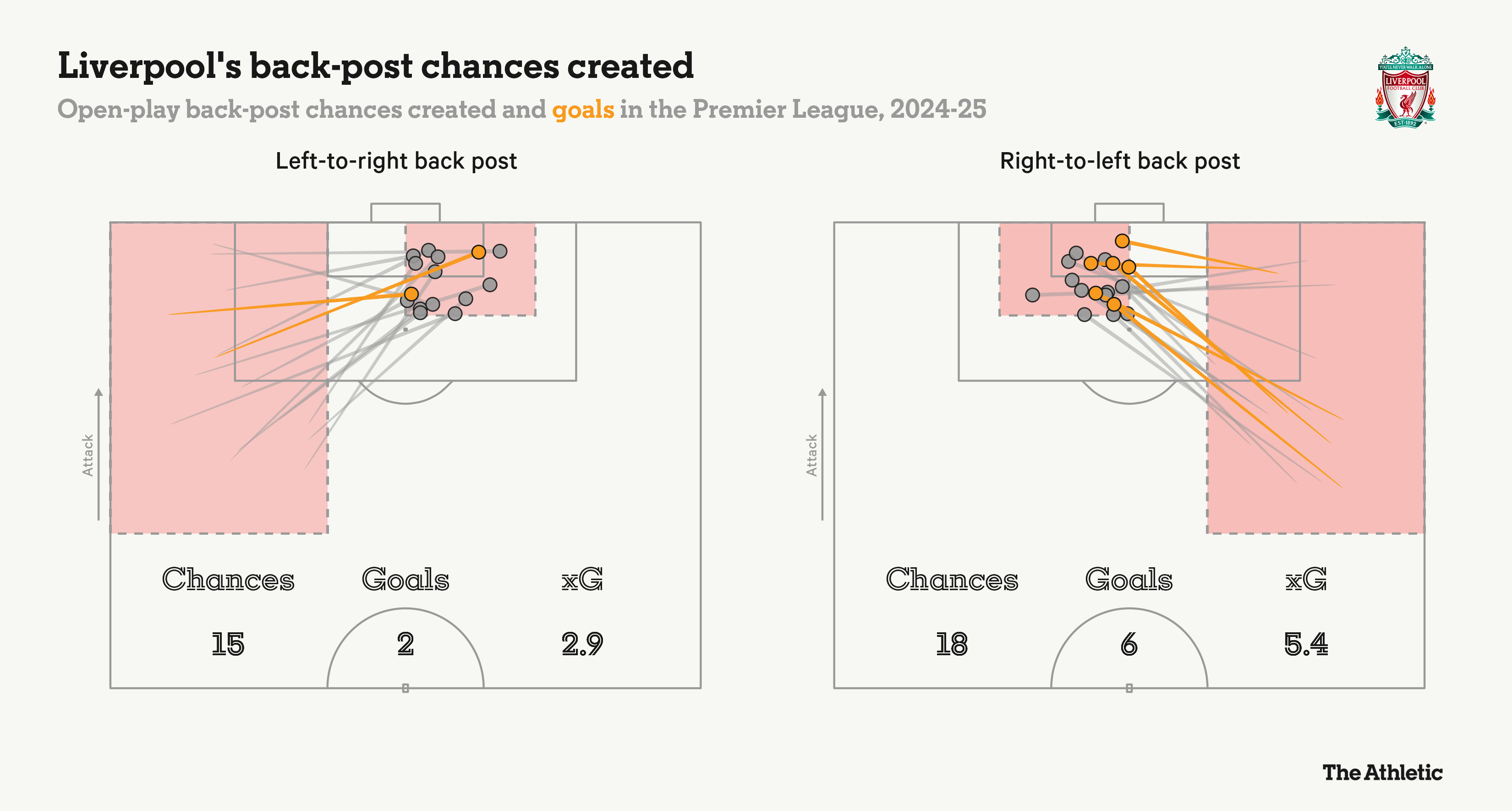

Alongside Fulham and Arsenal, Arne Slot’s Liverpool are among the most prolific teams to score via this method this season (eight goals) — with underlapping runs from a full-back or midfielder allowing Mohamed Salah or Cody Gakpo to drift inside onto their stronger foot to cross, often to each other with the opposite-side winger tasked with locking off the back post.

As the graphic below shows, Salah has built a near-trademarked cross to the left far post, consequently generating 5.4 expected goals (xG) — the most from the right flank in the Premier League.

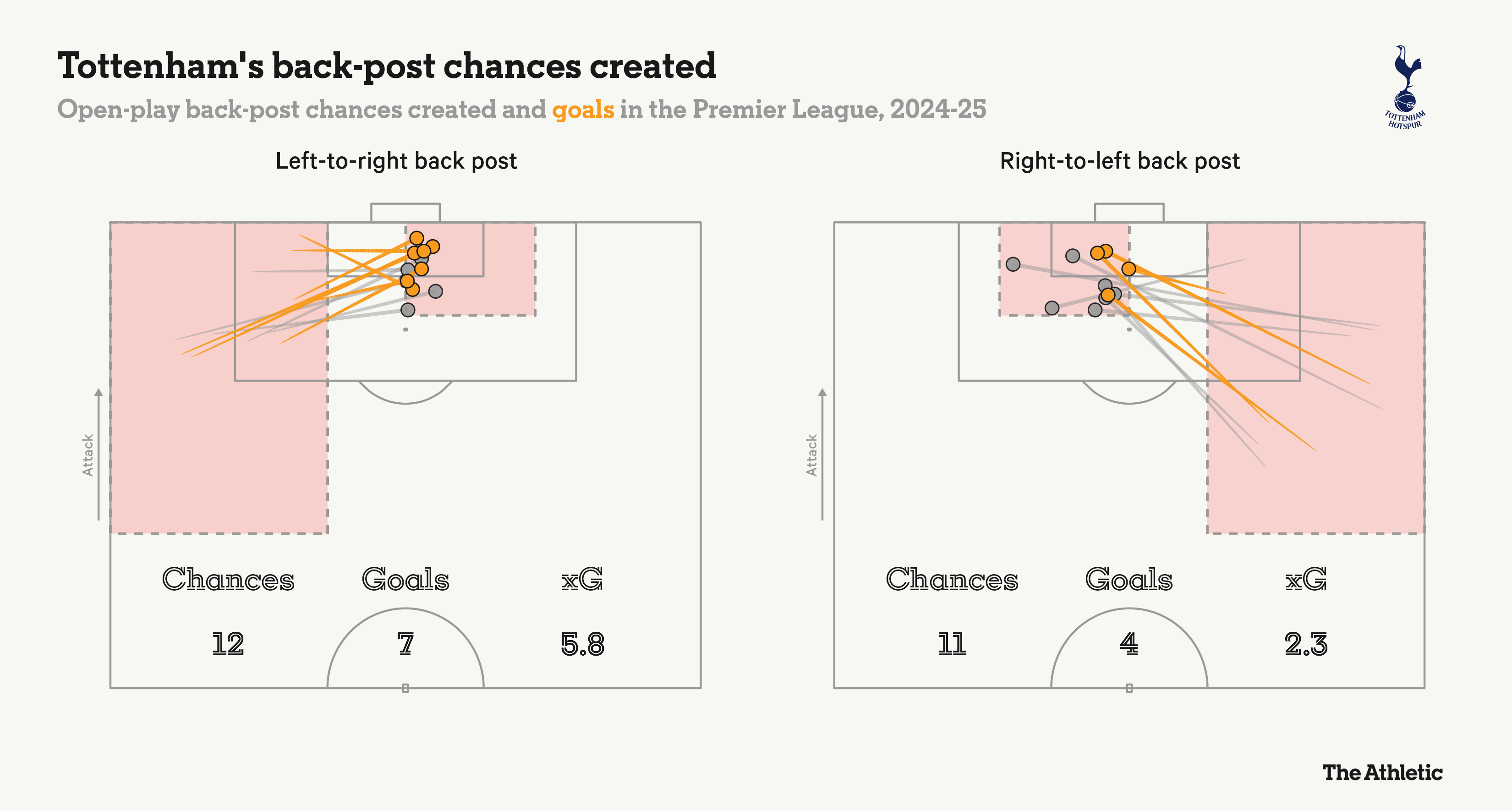

Liverpool’s eight goals are bettered only by Tottenham Hotspur, with Brennan Johnson in particular crafting an archetypal goal for himself — scoring eight goals from back-post crosses alone since he joined the club at the start of last season. His latest came against Ipswich Town yesterday.

Back-post goals have been a theme of Ange Postecoglou’s methods long before he joined Spurs. With the focus on his striker occupying central areas between the width of the goalposts, it is the job of his wingers to ensure they are occupying the opposite side when a team-mate is crossing.

Some teams do this better than others, but back-post chances have been part of a stable diet among the most creative managers in the division in recent seasons. The numbers simply back this up.

Knowing that the opposition will often attack in a front five, teams are increasingly aware of the gaps they might leave in their back line when defending in structured mid-to-low block situations.

Brentford, Newcastle United, and Chelsea are just three examples below where teams have dropped a winger or midfielder into the defensive line to add extra coverage — forming a situational back five to cover the space across the width of the pitch.

Defending in this way is often designed to stave off any runs through the defensive line, particularly the threatening half-space runs that can lead to one of the most dangerous crosses in the game: the cutback.

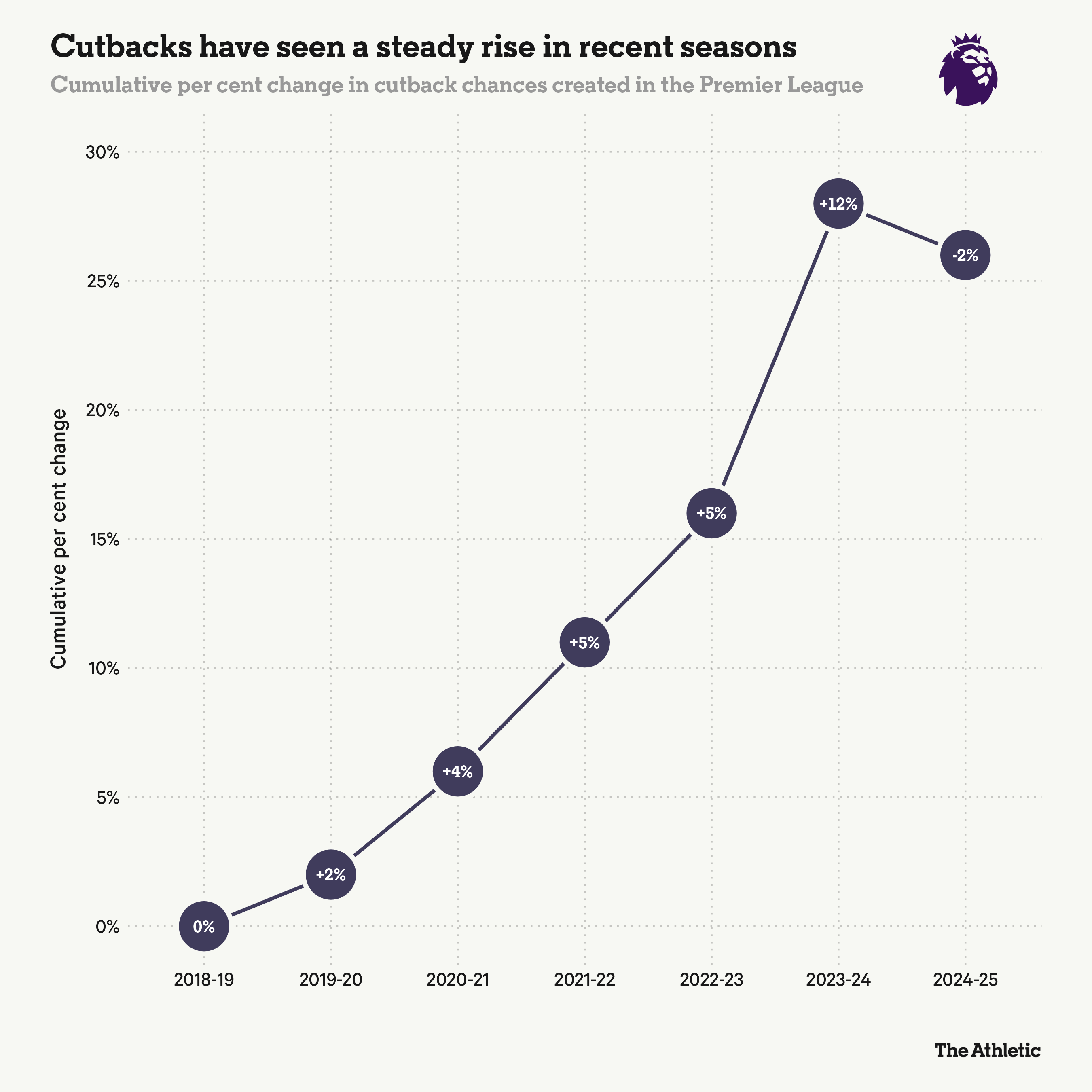

When executed properly, a cutback cross can be almost impossible to defend as the opposition retreats towards their goal line to leave space for an onrushing team-mate to attack. Returning to our cumulative per cent change of cutback chances created per game since 2018-19, there has been a steady increase in this method of attack — with a 26 per cent rise compared with six seasons ago.

Manchester City have been the kings of the cutback for most of Pep Guardiola’s time in the Premier League, and this is a clear approach that has been instilled in their players.

“I used to say in Manchester that the last player to arrive in the box is the first one to be able to shoot,” said City’s assistant manager Juanma Lillo in 2022. “I tell that to my strikers all the time: the closer you get to the goal, the further you are from scoring.

Advertisement

Despite their struggles this season, their 69 chances created via such means are head and shoulders ahead of any team — and it was on display as recently as last weekend.

As Savinho received the ball on the right wing, it was a simple drive to the byline that saw each of Newcastle’s back line retreat as one. Omar Marmoush held his run and did not have to work hard to find oceans of space to finish first time from Savinho’s cutback.

City have been the flagbearers for this type of cross for a long time, but the numbers suggest that this delivery is being used more widely across the league as a more repeatable method of attack.

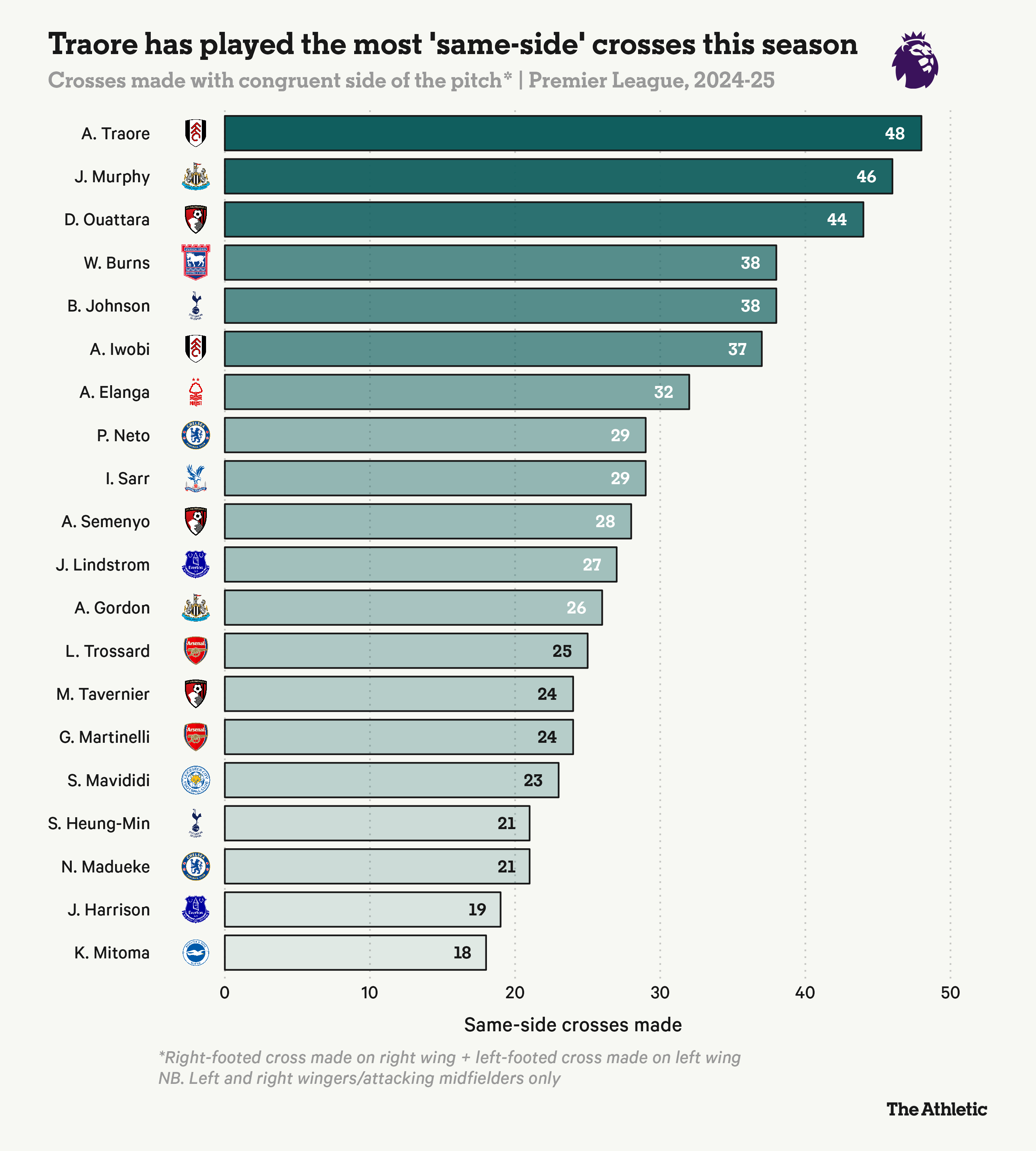

Finally, it is trickier to quantify this trend at the season level, but the past six months appear to have seen a return of a particular type of cross — wingers crossing from the flank that matches their stronger foot (ie, ‘same side’ crossing). With inverted wingers being commonplace in modern football, a return to ‘traditional’ wing play has become notable by its presence.

One example is taken from the versatile Savinho, who has shown some of his best form on the left flank when crossing from his stronger left foot. Assists against West Ham United and Leicester City were near-carbon copies of each other after a looping ball was put on a plate for Haaland to finish — for yet more back-post goals.

Another notable example is Newcastle’s Jacob Murphy, who has found some of his best form this season with driven crosses played to Alexander Isak to finish first time.

In this case, having a right-footed right-winger can be beneficial not only for passing angles but often provides a higher probability of an early pass being played — helping the striker to make his movement and time his run.

“He (Isak) just knows where I want to put the ball. When I get into certain situations, I’m looking to hit certain areas. He’s just living in that area,” Murphy told CBS Sports Golazo YouTube channel this month.

“We can already do half the job by being in the correct situations. Then it’s down to the execution of the final ball and the finish. We have struck up a great partnership and we need to keep doing that.”

Murphy has been rampant in making those crosses from the right flank. Only Fulham’s Traore has attempted more crosses as a ‘same-side’ attacking midfielder or winger in the Premier League this season.

This is all without considering the greater focus on crossing from set pieces, which has seen a well-documented surge in focus in recent seasons — with sharpened delivery and choreographed routines used to maximise dead-ball situations.

This all speaks to a growing trend in the Premier League, largely borne out of necessity as opposition teams find better ways to condense the space in dangerous central areas.

To find a solution to such tactical issues, the message is simple. If you can’t go through it, and you can’t go over it — go around it.

(Top photo: Jay Barratt/Getty Images)