There are 100 days until FIFA’s revamped Club World Cup begins with a match between Al Ahly and Inter Miami at Hard Rock Stadium in Miami Gardens.

The two teams kick off a month-long tournament on June 14, with the United States hosting some of the biggest clubs in world football, including Real Madrid, Manchester City, Bayern Munich and Juventus.

Advertisement

The U.S. only hosted a major men’s football competition nine months ago, but the lasting memory of 2024’s Copa America is arguably how bad the pitches were rather than how Lionel Messi’s Argentina defended their crown.

A mixture of NFL venues, MLS grounds and hybrid stadiums were used for the competition, which is run by South America’s soccer federation, CONMEBOL. Advance work was supposed to ensure the pitches were consistent across all 14 stadiums — however, players and managers lined up to criticise the playing surfaces, and it quickly became the tournament’s biggest talking point.

To prevent a similar problem at the Club World Cup and the men’s World Cup, which is being co-hosted by the U.S., Mexico and Canada in 2026, world football’s governing body, FIFA, which runs both competitions, has invested millions of dollars into research. Here is FIFA’s plan…

What were the pitch-related issues at Copa America?

“They knew seven months ago that we’d play here and they changed the field two days ago,” Lionel Scaloni, Argentina’s coach, told the assembled media after the Copa America’s opening game. “It’s not an excuse, but this isn’t a good field. The field is not apt for these kinds of players.”

Emiliano Martinez feels the grass at Copa America 2024 (Charly Triballeau/AFP/Getty Images)

Brazilian forward Vinicius Junior was also critical, saying to the press during the group stages that “Copa America is always difficult because of the pitches” before adding, “When we talk, CONMEBOL says we talk too much.”

On top of complaints about some pitches breaking up and being too dry, the dimensions at all the venues were also the smallest permitted for international games — 100 metres long and 64 metres wide.

For the Club World Cup and men’s World Cup, FIFA says the pitches will be their standard full regulation size (105m x 68m, an extra 740 square metres). They will also be natural grass, although the base will have synthetic stitching.

GO DEEPER

Why Copa America is being played on small pitches – and what it means

Is this why FIFA invested in research?

FIFA had an observation group at the CONMEBOL-run Copa America and was not oblivious to the concerns raised.

Even before the 2024 competition, they knew there would be several challenges to developing consistent pitches across three countries hosting the 2026 World Cup when you consider the different climates, altitudes and use of indoor and outdoor stadiums.

Advertisement

“It is always a sensitive subject around pitches and other tournaments,” Alan Ferguson, FIFA’s senior pitch manager, says of the Copa America. “It showed us how badly things can go wrong and be perceived by the players.

“It has also helped to steer us into a better place, and I’m quite comfortable with where we are going into the Club World Cup.”

Ferguson’s confidence comes from a significant investment — around $5.5million (around £4.4m) — in research. FIFA partnered with the University of Tennessee and Michigan State University in 2022 to launch a long-term research and development project. The goal was to produce faultless and consistent playing surfaces in time for next summer’s World Cup — and then the Club World Cup was added to the schedule.

“When you compare it to Qatar in 2022, the World Cup in 2026 is going to be hosted by three countries and in some stadiums that have never had natural grass,” Ferguson adds. “The challenges were fairly significant. I took a decision early on when we were in Qatar (which hosted the men’s World Cup in 2022) to replicate the small research station they had over there and upscale the whole thing.”

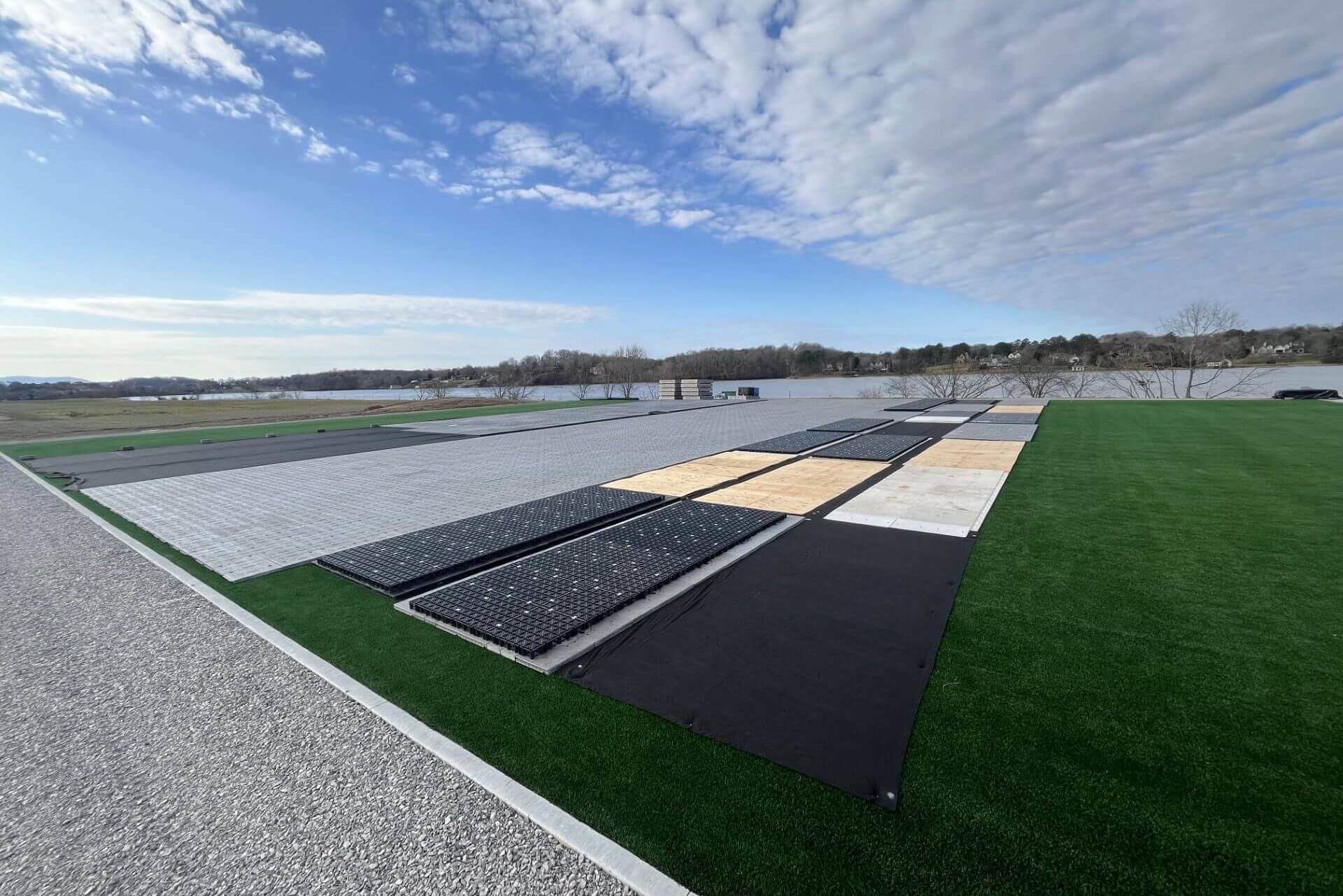

Some of the research being done for FIFA in Tennessee (FIFA/University of Tennessee)

What have they done?

“FIFA wanted evidence-based research and science to pull off the 2026 World Cup,” says Dr John Sorochan, a professor of turfgrass science and management at the University of Tennessee.

Sorochan has been heading up the investigation and estimates they have done “close to 70 different independent research projects” up to now.

“You need to know what is best for each stadium when it comes to simple management, so that is mowing, fertilisation, irrigation and cultivation,” Sorochan says. “You need to keep them so that the pitches don’t wear out too fast, but they can still have the ability to recover.

“We’ve done some ballistic high-speed ball impact tests to look at how the ball will bounce. So, if you think of playing a soccer match and you drop it back to the defender and he switches it to the other side, then you want the ball to come in and not bounce so they are trying to stop it with their chest to go out of bounds.

Advertisement

“You want it to be at their knees or lower, and that is the target we have been shooting for, for the ball-to-surface interactions as well as the speed of the ball or the roll on the surface from a pass.

“And then we want it to be similar for good footing and measuring it so a player can train and go from one stadium to the next and know that they won’t have to be thinking about their footing because they can run and play and know that they are going to have sound footing.”

GO DEEPER

‘It’s not normal grass’: Why field conditions at Copa America are causing concern

What challenges have they encountered?

The World Cup presents unique challenges because of those three host countries. The Azteca Stadium in Mexico City, for example, sits several thousand feet above sea level. While this may not sound too consequential, it certainly is from a pitch perspective due to FIFA requiring all surfaces to be consistent, whether in Vancouver, Canada, or Guadalajara, Mexico.

“We’ve got five indoor stadiums and eight stadiums that have artificial turf that have to be converted,” Sorochan explains. “You need the pitch, whether it is growing inside under artificial lights or at a normal field outside, like in Kansas City, or at several thousand feet altitude, like the Azteca Stadium in Mexico, to play the same.

“Those are the challenges that we look at, and knowing again that each stadium has its own unique environment, climate and condition. But we want to make sure that that pitch from game one through game four, game seven or game nine, however many they have in that stadium, is going to be the same.

“And then you want that stadium to be as close to the same as every other stadium, so that has been the challenge and what we work to strive for.”

Ferguson, left, FIFA president Gianni Infantino, centre, and Sorochan, right, at the University of Tennessee last month (FIFA/University of Tennessee)

What about the Club World Cup?

The revamped Club World Cup meant Ferguson and Sorochan had to expedite their research, but it also allowed them to gather invaluable insight into how the pitches perform. Any issues that may arise can be ironed out before the World Cup begins a year later.

“The Club World Cup got thrown into the mix a couple of years ago,” Ferguson notes. “Typically, FIFA would look at a test event going into a men’s World Cup. It used to be the Confederations Cup, for example.

Advertisement

“It is unfair to call the Club World Cup a test event because it is a major tournament in its own right, but we will face the same issues in 2025 as we will in 2026, so it will provide us an insight into what is ahead for the final 12 months.”

Will the research make a difference?

“Whether it’s an overlay system, a temporary system, or a more traditional type of pitch, they have to behave the same,” says Ferguson.

“And it’s been getting these temporary elements to give the same response to the foot and the ball that has probably been the biggest challenge, but we are quite comfortable that a ball will bounce the same in Dallas and Kansas City as it will in Washington and Mexico City.”

Who is paying?

FIFA has invested in the research, but the host venues need to pay for the changes and installation. These costs will stretch into seven figures.

“It is part of any host country taking on a World Cup, whether that’s a football pitch, fan access, or a whole multitude of other things that go across the contract,” Ferguson says. “It’s not cheap, but then you are talking about the biggest tournament in the world with the biggest players in the world.

“It’s always going to be a two-way discussion, but principally the host country and the host cities and the venues have to fulfil the requirements. It’s the same with any major sporting event — the Olympics, the World Cup, the women’s World Cup, the Rugby World Cup. They’re all principally the same in how they are rolled out in these countries.”

New Jersey’s MetLife Stadium will host the 2026 World Cup final (Al Bello/Getty Images)

Have they tested their research?

When Canada played Mexico in a friendly match in September at AT&T Stadium in Dallas, Ferguson and Sorochan tested their evidence-backed system.

“We tested what’s the best system and the players raved about the condition of the pitch,” Sorochan says. “We know it can even be better for a World Cup, but that was putting the research to action and it actually being deliverable.”

Advertisement

The feedback from players led Sorochan and Ferguson to believe they were “very, very close”, in Ferguson’s words, to where they wanted to be.

“A lot of very positive press came off of that game from the players and the coaches, not from us, which was great because ultimately these are the guys that use the fields,” Ferguson adds. “They have to be happy, and if they were reporting positively, it told us we are heading in the right direction.”

(Top photo: Lionel Messi on a Copa America pitch in 2024; by Sarah Stier via Getty Images)