This is the first in a new series on The Athletic looking back at the winners of each World Cup, from Uruguay in 1930 through to Argentina in 2022.

Introduction

When Uruguay won the right to host the inaugural World Cup — partly based around the fact they were celebrating their centenary as a nation, and partly because they were considered the strongest side around after winning the 1924 and 1928 Olympic football tournaments — it was both a blessing and a curse.

Advertisement

The curse was that they were handed only a year to put together a tournament of unprecedented size for a single sport. The inevitably-named Estadio Centenario, where Uruguay would play all their matches, was only declared ready five days into the tournament after three teams of workers constantly rotated around the clock on eight-hour shifts, so the hosts started later than everyone else.

The 100,000-capacity arena was temporarily capped at 80,000, with scaffolding around the outside showing how recently the project had been finished. Even Uruguay’s first opponents, Peru, had already begun their tournament, as Group 3 featured just three teams in an awkward, 13-team competition.

That was another part of the ‘cursed’ element; Uruguay were faced with the tricky task of convincing the great European nations to attend. Some, including the Home Nations, were not part of FIFA at this stage, and were never going to participate. Italy, who had been the popular European choice for host country, stayed away in protest, and many other European sides followed suit.

Of the four European nations who did travel, Belgium and Yugoslavia were not amongst the elite, Romania only entered once their King insisted on their participation (and on picking the squad himself) and France sent a (below-strength) squad primarily as they’d played such a major role in the creation of the World Cup. At this point, a trip to South America took three weeks by ship — and the European nations travelled together on the Conte Verde steamboat, keeping up their fitness by running laps of the ship. Oh, and Egypt had to withdraw after missing their connection due to a storm in the Mediterranean.

The French team pictured on their way to the tournament in Uruguay (STAFF/AFP via Getty Images)

Uruguay’s blessing, of course, was home advantage. This has traditionally been very strong throughout World Cup history, although less so in recent years, with better preparation for travelling nations and more tournaments hosted by nations with weaker football sides. But in 1930, while others faced long journeys getting to Uruguay, then encountered logistical problems and cultural differences in the country, the hosts enjoyed a productive training camp, home comforts and a noisy, partisan and sometimes violent support.

So, by winning the right to host the first World Cup, Uruguay immediately made themselves strong favourites to win it.

The manager

In 1930, the precise role of a football manager was not universally agreed upon. At this stage England, for example, simply didn’t have one — they merely had a selection committee. Uruguay’s opponents in the final, Argentina, had something approaching a modern double-act of ‘technical director’ and ‘coach’, but Uruguay’s Alberto Suppici was probably more of a ‘trainer’ in British parlance, who focused primarily on physical conditioning, to the extent that in Ian Morrison’s comprehensive history of the World Cup, he suggests that “Uruguay did not have a team manager for the tournament”.

Advertisement

A former left-half for Montevideo-based Nacional, Suppici was considered a gifted all-round athlete, excelling at rowing, swimming, boxing and athletics as well as football. Suppici’s month-long training camp focused on very long runs (at a constant speed), elements of strength conditioning, a major focus on reaction times, and also some seemingly forward-thinking breathing exercises.

Suppici was also a big disciplinarian, imposing a strict curfew on his players. When goalkeeper Andres Mazali was caught sneaking back from a night out midway through the training camp, he was omitted from the squad entirely, having previously been considered undroppable. After that bombshell, the curfew was respected, and in that light it seems harsh to suggest that Uruguay didn’t have a team manager — Suppici was clearly in charge of more than just fitness.

Still, there are few signs Suppici was a tactical genius, or even concerned with tactics at all. It seems likely one of his assistants, former national team captain Pedro Arispe, who had won the 1924 and 1928 Olympics, was more focused on the strategic side of the game and worked with the players to talk tactics. In fact, some reports suggest the players essentially picked the starting XI amongst themselves.

The victorious Uruguay side at the 1924 Olympic Games (Archives CNOSF/AFP via Getty Images)

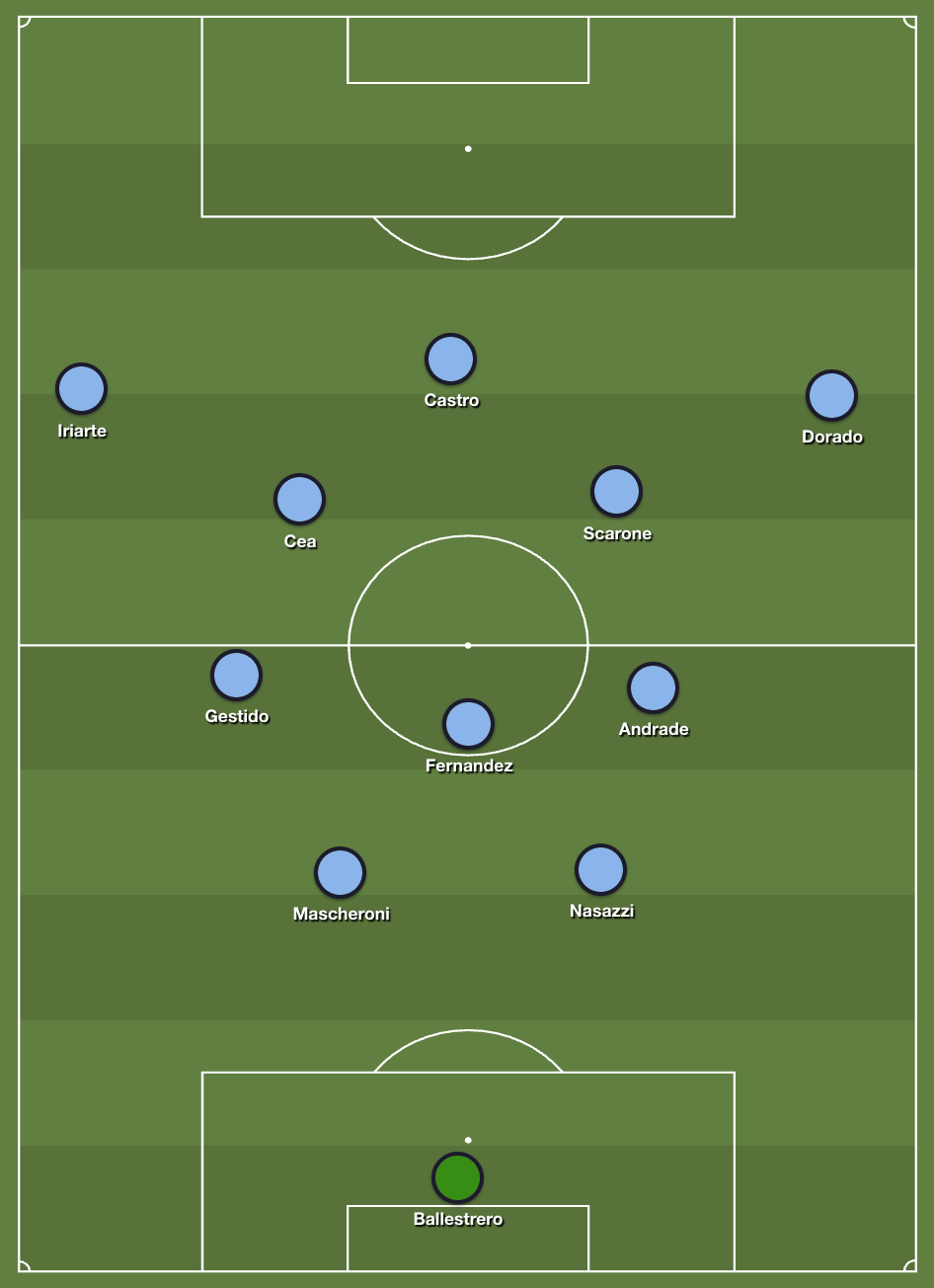

Tactics

In 1930 there was little tactical variety on show — the majority of sides, including Uruguay, played a 2-3-5 formation. Although the transformative 1925 offside change would eventually result in the centre-half (the central of the midfield three) dropping to become a centre-back, that wasn’t in evidence here. Uruguay’s centre-half Lorenzo Fernandez was a creative player, who sometimes deputised in attack.

Uruguay were particularly strong down their right flank, where their best players were positioned.

The right-half, Jose Andrade, was a fast and technical player who lacked in physique, but was renowned for his close control. He was probably the game’s first world-renowned Black footballer. Having previously retired from international football after the Olympics, he returned after Uruguay won the right to host this competition. Ahead of him was inside-right Hector Scarone, a genuine superstar whose reputation was good enough for him to be signed by Barcelona in 1926. A small and slight player, he was probably ahead of his time, and nicknamed ‘The Magician’ because of his ball skills.

Advertisement

On the left, Uruguay started with Domingo Tejera in defence, but after a nervy opening performance against the speed of Peru, he was replaced by the more solid Ernesto Mascheroni.

Uruguay were initially credited for their short passing game, and the interplay between their five attackers drew praise. It was “a unique playing style, a home-grown amalgamation of combination play and joy,” writes Martin da Cruz in his history of Uruguayan football.

However, in the final, they changed approach and played more long passes, particularly after the break. These are likely to have been diagonal balls rather than what we consider ‘long balls’; the pitch at the new Estadio Centenario was the maximum allowable width, 100 yards (the current Premier League standard is 74 yards, for reference) and provided plenty of space to exploit out wide.

Key player

In attack, Uruguay were more harmonious and collectivist than most World Cup sides of the first few decades.

At various points, either of the two inside-forwards could be considered their best player — there was a reason for Scarone’s magical nickname, while Pedro Cea bagged a hat-trick in the semi-final, a 6-1 win over Yugoslavia.

Peregrino Anselmo started three matches as the centre-forward, while the powerful Hector Castro — notable because he was missing a forearm after a childhood accident with an electric saw — played instead of him in the first and last games. Both wingers contributed impressively too, providing a goalscoring threat, while centre-half Fernandez was considered man of the match in the final.

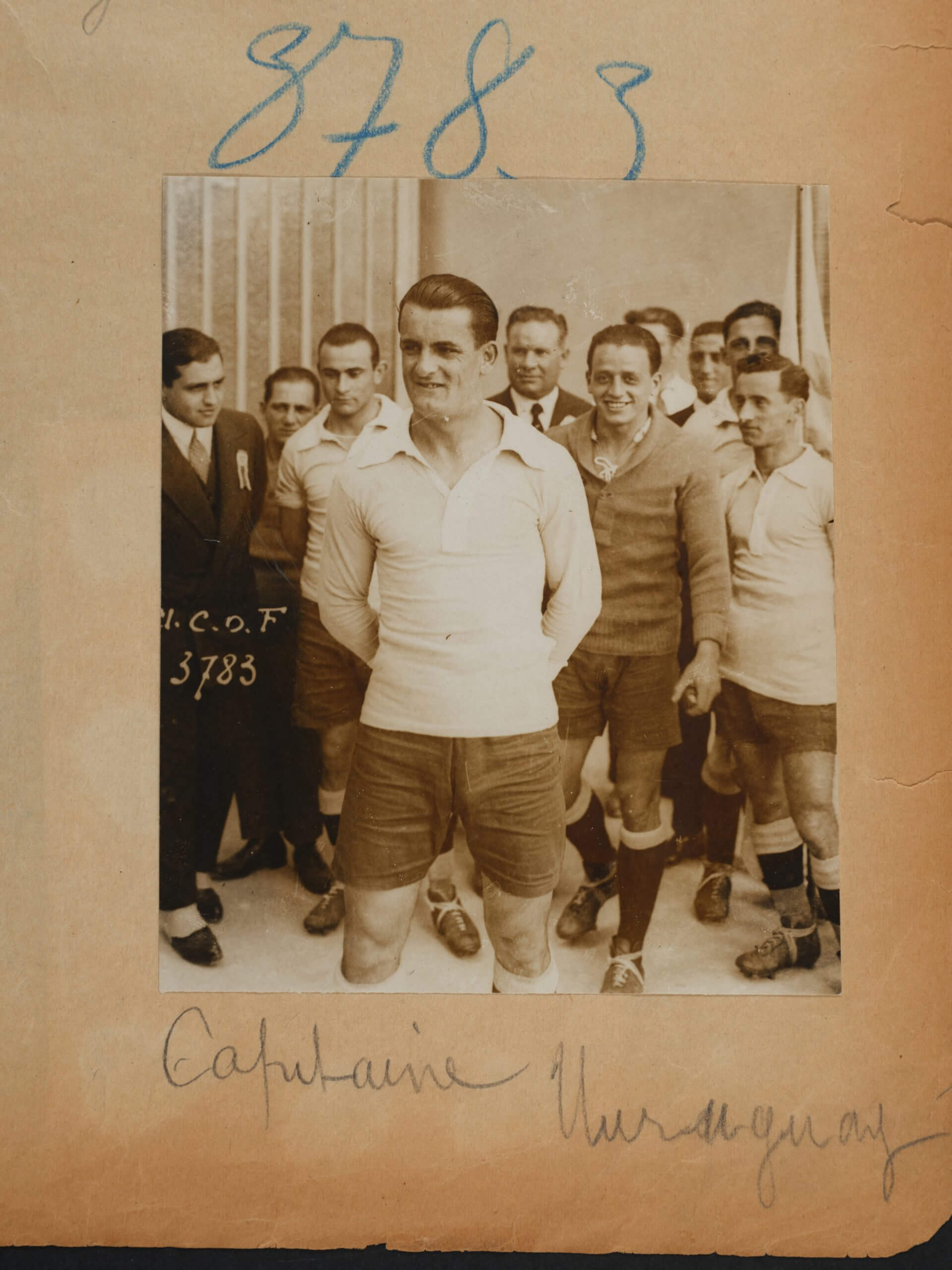

But the key player was probably captain Jose Nasazzi, nicknamed ‘The Grand Marshal’. At this stage, defenders just defended. Nasazzi, the right-sided of the two defenders, was strong, physical and intimidating, and there are no signs he was particularly gifted in possession. But he was regarded as the best defender in an attack-minded tournament, and started a legacy of rugged, no-nonsense Uruguayan centre-backs that lives on until this day.

Uruguay captain Jose Nasazzi: ‘The Grand Marshal’ (Archives CNOSF/AFP via Getty Images)

The final

Uruguay versus Argentina was the expected final. Two years beforehand, they’d contested the Olympic final in Amsterdam, with Uruguay running out 2-1 winners in a replay after a 1-1 draw. They weren’t simply neighbours; they were serious rivals, whose recent meetings had been extremely aggressive.

In this tournament, Uruguay and Argentina had reached the final with 6-1 wins over the winners of the other two groups, Yugoslavia and USA, respectively. A local derby meant a decent travelling contingent from Argentina, and a fearsome atmosphere around Montevideo beforehand. The Argentine players were under police guard amongst reports of death threats. The travelling fans were delayed because of extensive checks for guns by customs officers. The referee for the final, Belgium’s John Langenus, insisted upon life insurance for himself and the two linesman before agreeing to proceed. This was an extremely hostile game.

Advertisement

Uruguay raced into the lead when Dorado, the right-winger, smashed home from a tight angle with a shot that went through Argentine goalkeeper Juan Botasso’s legs. Argentina’s right-winger Carlos Peucelle then equalised, before the true superstar of the tournament, Argentine centre-forward Guillermo Stabile, put his side ahead, possibly from an offside position.

Uruguay, 2-1 down at half-time, rallied with a more direct approach after the break, and emerged victorious. Cea equalised after a direct dribble, left-winger Santos Iriarte belted one in from long range, and then centre-forward Castro nodded home the clinching goal to make it 4-2.

Footage from the game — and from the tournament overall — is somewhat unclear. But we can be surer of what happened after the final whistle, which is rather different from what we expect today.

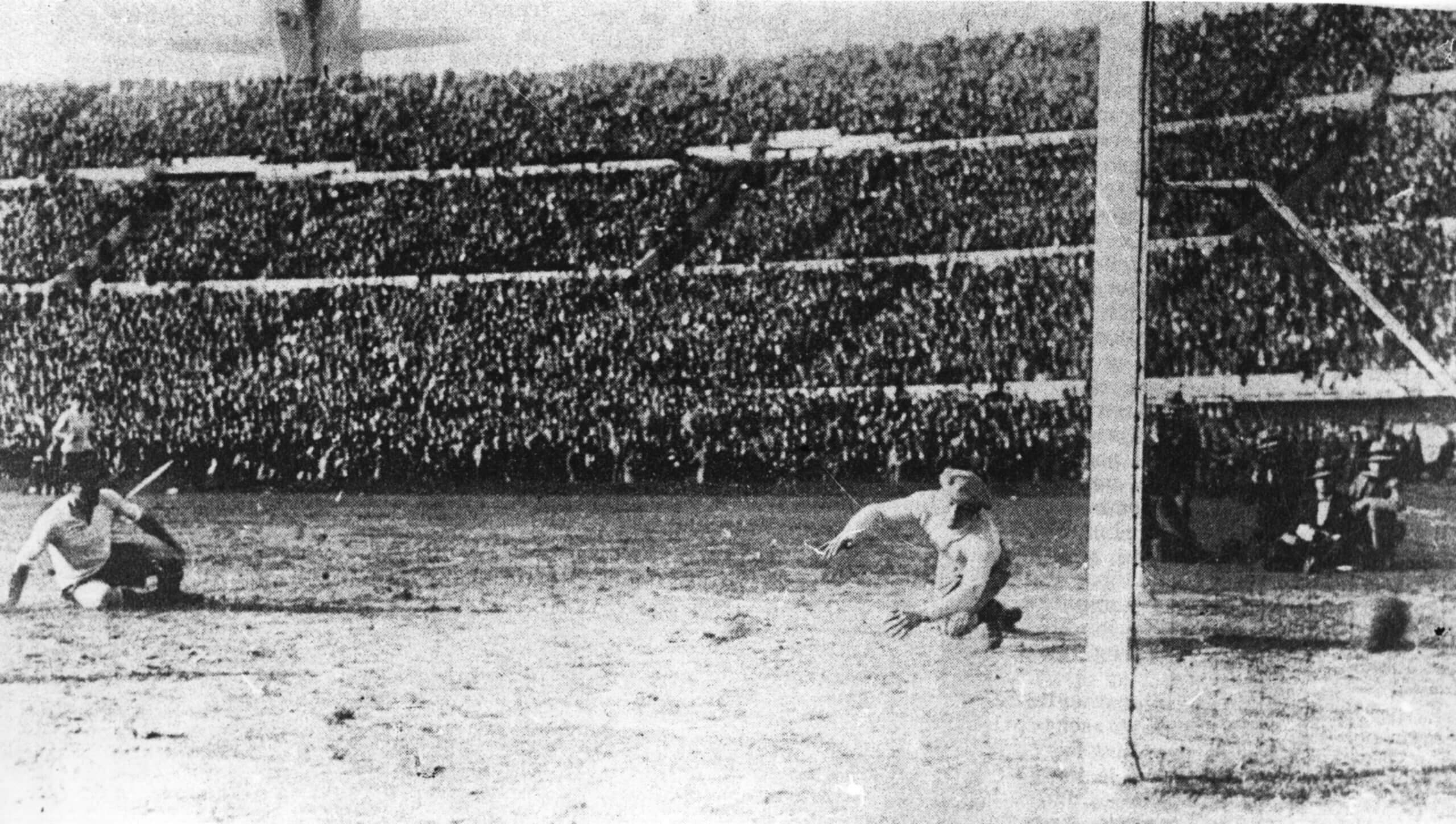

Officially 68,346 spectators attended the first-ever World Cup final (Keystone/Getty Images)

First, there is no record of Nasazzi being handed the World Cup trophy on the day. In fact, while the trophy seemingly stayed in Uruguay for the majority of their four-year spell as world champions, there was barely any sighting of it — it was seemingly stored in a vault in a bank somewhere in Montevideo. Confusingly, there are photos of right-winger Dorado holding a large silver trophy, but even FIFA are unsure of what this trophy was, and where it ended up. There was also a delay in the players being awarded medals — this presentation only happened four months afterwards.

Uruguay conducted what would today be considered a lap of honour, and some suggested this was an impromptu move and effectively started the tradition. The following day was declared a national holiday in Uruguay, while across the water in Buenos Aires, the Uruguayan embassy was trashed by Argentina supporters.

While the tournament had some teething problems, and one group game drew an attendance of just 300 spectators, there was little doubt that the World Cup final had attracted serious interest from the two countries who contested the final. Back in Europe, the tournament was almost ignored by the countries who didn’t participate.

The defining moment

Iriarte’s goal to make it 3-2 in the final was the crucial goal in terms of deciding the outcome, and also the best of the game.

Collecting the ball on the left, with Argentina’s defenders seemingly guarding against a dribble or a pass into the box and therefore backing off, Iriarte unleashed a shot from 25 yards out that surprised everyone — including the cameraman, as the grainy video footage from the final doesn’t quite capture the moment the shot was taken, and is instead focused on what is happening inside the box. The ball flew into the top corner at the goalkeeper’s near post.

You might be surprised to learn…

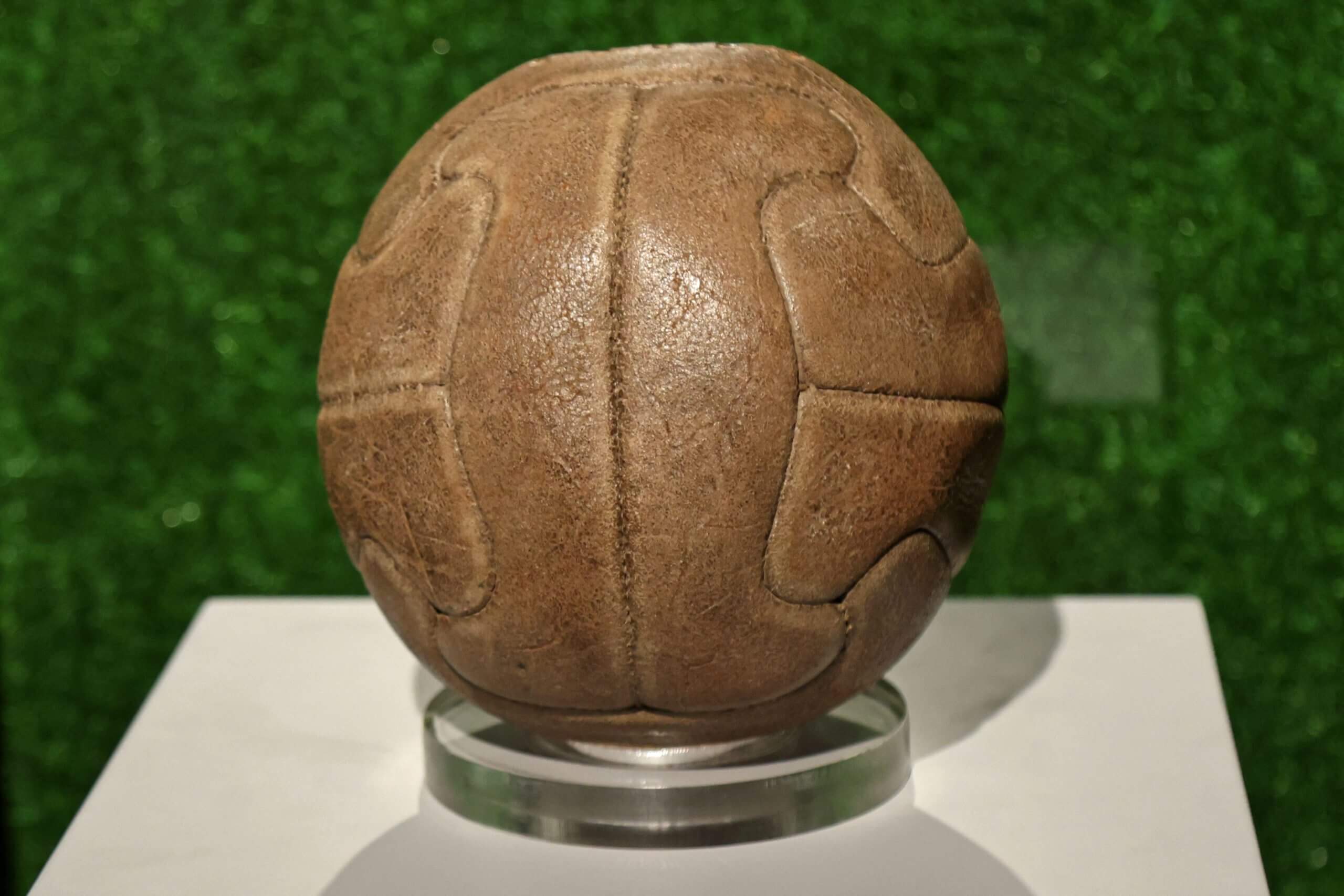

There was an almighty dispute before the final over the nature of the football. Both Uruguay and Argentina had been allowed to use their own ball throughout the tournament, and therefore ahead of the final there was a stand-off. Oddly, it was effectively a battle of Britain: Uruguay favoured a ball imported from England, Argentina’s was made by a Scottish company.

Advertisement

Legend has it that the match was played with the Argentines’ favoured ball before the break, and the Uruguayans’ favoured ball in the second. Neatly, Argentina were 2-1 up at half-time, and Uruguay won the second half 3-0.

Granted, this is probably the only famous tale from the first World Cup final — so you might not be surprised to learn it. But you might be surprised to learn that it’s probably not true.

There’s little record of the half-time switch in reports from the time, and there’s no photographic evidence to support the idea the ball was switched. As Paul Brown pointed out in a 2018 issue of When Saturday Comes magazine, referee Langenus declared in his memoir that the Argentine ball was chosen after a pre-match coin toss. Langenus doesn’t mention any subsequent switch, and it seems unlikely he would neglect to mention such a fundamental part of proceedings.

The (Argentine) ball is currently on display in Manchester at the National Football Museum. No one knows where the Uruguayan ball is, probably because it didn’t actually play any part in the match.

The (only?) ball used in the final is on display in Manchester at the National Football Museum (Karim Jaafar/AFP via Getty Images)

Were they clearly the best team?

With the significant caveat that many teams who might have stood a chance of winning the tournament didn’t compete — Italy and England, for example — it’s difficult to argue against Uruguay. After all, they had already established something of an aura following their successes in the Olympics in 1924 and 1928, and won all four matches here.

The first champions of the world (Hulton Picture Library/ALLSPORT)

That said, Argentina won five from five — their group had four teams — and reports from the final suggest it could have gone either way. Argentina led for 20 minutes, and even when Uruguay led 3-2, Argentina twice hit the woodwork. Might things have been the other way around had the tournament been played in Argentina rather than Uruguay? Perhaps. But then home advantage didn’t detract from Uruguay’s success. Indeed, there was rightful pride in Montevideo that they hadn’t simply performed well on the pitch, but successfully pulled off the hosting of the tournament, which took place entirely in one city — for the last time until Doha did so (more or less) in 2022.

Still, it was notable that the winners were the hosts, and the runners-up were their closest neighbours. Home advantage was an extremely strong factor at this stage — as was to be proven four years later in Italy.

(Header design: Eamonn Dalton; photo: Getty Images)