It is a problem dominant football teams are experiencing across the world: with so many opposing sides deploying a low block, meaning they sit deep on their 18-yard line for the majority of the game, how do you find a way to goal?

With space behind the defence strangled and the centre of the pitch condensed, plotting a course requires precise combination play. Most teams have to go around the block but that usually means crossing the ball, and statistically those do not translate into goals very often.

In light of those convoluted routes, Arsenal captain Martin Odegaard has made the executive decision that going over all those bodies is the best policy.

It has been part of his playmaking repertoire for years but, lately, the Norway midfielder has been attempting his trademark ‘scoop pass’ several times a game.

It tends to be played from the outskirts of the penalty area. When Odegaard finds himself with time and space, he waits for a gap to appear. If one is not forthcoming, the next-best option is dinking the ball into the space between the opponents’ back line and the goalkeeper.

And it is usually performed from a stationary position. The scooping motion requires stability to slide the toe of your boot underneath the ball and then lift to create a looping trajectory.

Whole games will pass without anyone attempting one even once, but the 26-year-old seems determined to make it a key part of Arsenal’s attacking playbook.

In the 1-1 draw with Manchester United at Old Trafford last weekend, he tried it twice. One found Declan Rice, whose chest-down and volley was blocked.

But in the 14th minute, he created arguably the best chance of the game.

Receiving the ball 25 yards out, Odegaard initially saw Leandro Trossard outnumbered four to one with no room to slide the ball through a gap. However, the picture changed when the Belgium international made an arcing run behind United’s static back three.

Odegaard lifted a pass over their heads and into his path. Unfortunately for Arsenal, Trossard lost track of the flight of the ball and was unable to get a clean strike in.

The scoop pass is a piece of skill former Denmark midfielder Michael Laudrup mastered in the 1980s and 1990s.

His most beautiful execution of it came for Barcelona against Osasuna in the 1993-94 season, when he played a variation using the outside of his boot, creating a chance which Romario converted. It placed 51st on the list of the club’s greatest goals, and his team-mate Albert Ferrer said it exemplified why Laudrup was the “master of the blind pass”.

Advertisement

It is a pass that has been favoured by players schooled at Barcelona. The Catalan club’s famed midfield duo of Andreas Iniesta and Xavi used it frequently as their telepathic relationship with the forwards in that side meant they got the timing of the scoop and corresponding runs down to an art.

Ronaldinho also set up Lionel Messi’s first-ever Barcelona goal using this method. He laid on an earlier ‘goal’ for the Argentinian in identical fashion that night but it was ruled out for offside.

Chelsea’s Gianfranco Zola delivered a sublime scooped pass for Gustavo Poyet to scissor-volley home against Sunderland on the opening day of the 1999-2000 Premier League season, while Paul Pogba delivered a longer-range version for Juventus to tee up Stephan Lichtsteiner in 2015.

[embedded content]

The most recent example of it in the Premier League came two seasons ago, when Chelsea midfielder Enzo Fernandez scooped a ball into the path of Kai Havertz, who then lobbed onrushing Leicester goalkeeper Danny Ward.

Other proponents of the scoop pass include Johan Cruyff, Eric Cantona, Paul Scholes, Dimitar Berbatov, David Silva, Cesc Fabregas, Thiago and Pedri. It is a cluster of footballing names that define both poise and grace.

Yet, it has not become a common sight in football. Compared to the rapid uptake of the ‘Dilscoop’ in cricket, which was popularised by Sri Lankan batter Tillakaratne Dilshan in 2009 when he crouched below the flight of the approaching ball and hit it backwards over the wicketkeeper standing behind him, the scoop pass has not been widely adopted by clubs as a solution to the problem of low blocks.

Is there a reason for that?

Odegaard is bringing it to the forefront having attempted it seven times in the past four league games but none of the seven resulted in a shot at goal.

With questions mounting over Arsenal’s capacity to create high-quality chances, the ‘Odescoop’ has become a source of both wonderment and frustration. Some see it as an inspired piece of ingenuity that should be exploited but others view it as a trick that is aesthetically pleasing but inefficient.

Advertisement

He has shown the scoop can be successful, serving as an overpass taking a team straight to the opposition goal.

Against West Ham in November, he played a return pass to Bukayo Saka by lofting the ball over a sea of claret-and-blue jerseys who did not track the England forward’s run. Saka was able to volley across the six-yard line for Trossard to tap in.

While most short passes are delivered with the inside of the foot to ensure accuracy, and most longer ones are struck with the laces of the boot to ensure the ball travels quickly, the striking action of both still requires a backswing of that leg and a follow-through.

The scoop pass is different. It requires no back lift, so it a) can be delivered in an instant and b) provides no visual cue for the defenders to read.

Similar to a bunker shot in golf, contacting the ball from underneath means it pitches higher. But unlike a chipping action in football, where the player will strike the bottom of the ball without following through to produce elevation, the foot stays attached to the ball for longer to guide its path.

This is a pass all about feel. Once the foot is under the ball and has left the ground, a subtle flick of the ankle sends it forward to create the dipping motion that will bring it back down quickly.

With little space between defence and goalkeeper, there is a small target area to find. But with opposing teams holding an offside line and often preoccupied by the ball-carrier at the edge of their penalty box, a player making a short burst beyond a static line of defenders is very hard to stop.

Do they drop deeper and risk playing everyone onside, or step out to try to block the pass but in doing so risk opening up a passing lane along the ground?

This is the trap Chelsea fell into last season when Arsenal’s Ben White ghosted behind five of their players and volleyed a shot into the far corner.

Brighton, too, were caught out by Saka playing inside and then continuing his run.

They may have thought they had blocked the pass but, no matter how narrowly a team stick together in their low block, it does not prevent Odegaard from scooping the ball over them.

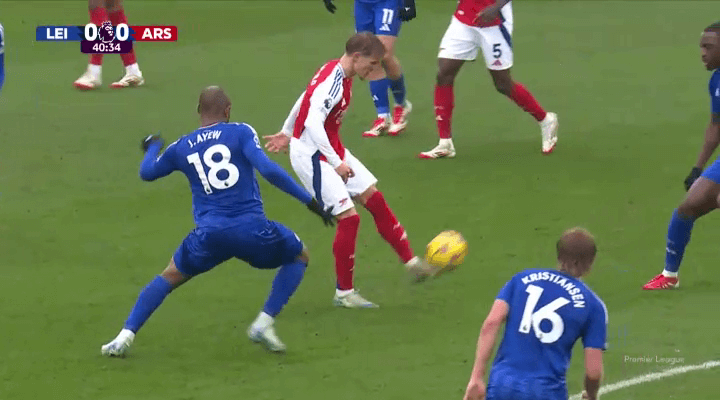

The difficulty of converting such a pass is that it hangs in the air and so does not usually present the easiest of finishes. Even though Trossard was twice picked out close to goal in this manner against Leicester last month, he was unable to get a shot off on either occasion.

The GIF below shows the problem with playing a straight scoop pass — the ball comes directly over the intended finisher’s head, which in this case meant Trossard had to try to time a volley as it dropped over his shoulder.

The second occasion was a much more realistic chance of scoring a goal. Odegaard was central and Trossard had a great angle to attack the ball.

Raheem Sterling was free in the middle and waiting for a square pass similar to the example above against West Ham but Trossard tried to go with his stronger right foot when he should have played it with his left.

Odegaard cannot eliminate players on his own. He requires team-mates to be on the same wavelength as him. He is currently missing two of his most trusted conspirators, Saka and Havertz, through injury, which is possibly why the scoop pass become a more regular weapon.

As an attacking force, Arsenal are a team designed around their captain’s specific, small-space skill set. Perhaps the scoop pass is an expression of how they have become too particular as a result of the requirement for intricacy.

Arsenal will be hoping that if the pass is unleashed against Chelsea at the Emirates Stadium on Sunday, the end-result will be Robert Sanchez scooping the ball out of his net.

(Photo: Glyn Kirk/AFP via Getty Images)