West Ham co-owner Daniel Kretinsky is exploring the possibility of selling his stake in the Irons and reinvesting in another club, TBR Football can exclusively reveal.

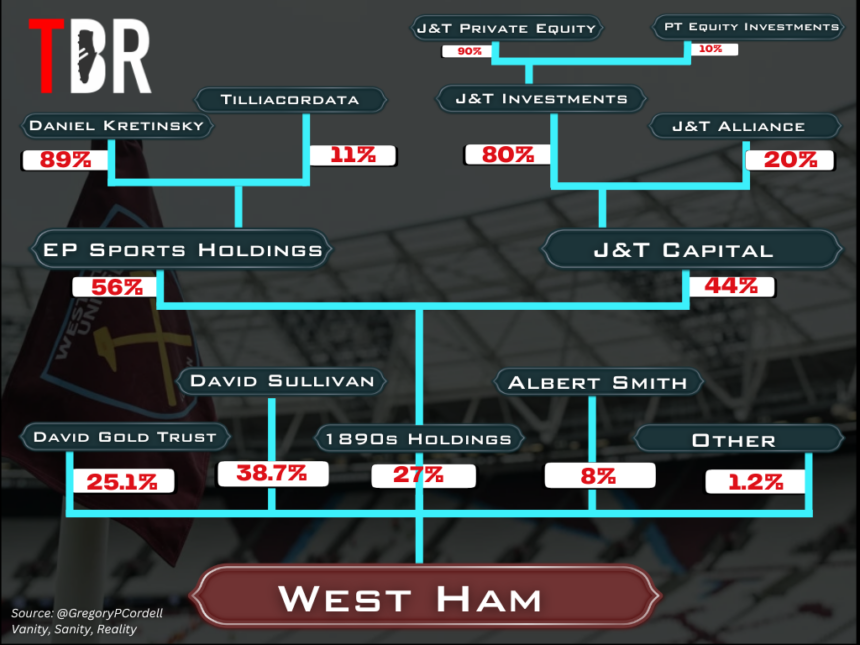

Kretinsky, the sundry tycoon from the Czech Republic, bought 27 per cent of West Ham’s equity in November 2021 and was at one point presumed to be nailed on for a full takeover.

The deal worth approximately £200m included an option for David Sullivan, the Hammers’ largest individual shareholder, to sell his shares to Kretinsky at a set price.

Photo by Vince Mignott/MB Media/Getty Images

Other shareholders could also theoretically be looped into the would-be deal, providing a possible exit route for Vanessa Gold – the daughter of the late David Gold, who is looking to sell a chunk of her shares.

However, Sullivan has not exercised that option. Meanwhile, Kretinsky has said he is not actively pursuing a full takeover.

Significantly, he has been more than a little preoccupied with a nebulous, historic and controversial buyout of Royal Mail, which will be the first time the British institution passes into foreign ownership.

That deal, which at £3.6bn will be worth significantly more than any takeover in football history, was approved by the UK government in December but has been delayed by geopolitical issues.

West Ham meanwhile have endured a topsy-turvy season, but there have been green shoots since the exits of Jolen Lopetegui and sporting director Tim Steidten and the appointment of Graham Potter.

They are 16th in the Premier League table, though with twice as many points as Ipswich Town, the team currently occupying the final relegation place. Attentions have already turned to preparations for 2025-26.

| Position | Team | Played MP |

Won W |

Drawn D |

Lost L |

For GF |

Against GA |

Diff GD |

Points Pts |

| 13 | 29 | 10 | 7 | 12 | 37 | 40 | -3 | 37 | |

| 14 | 29 | 10 | 4 | 15 | 55 | 43 | 12 | 34 | |

| 15 | 29 | 7 | 13 | 9 | 32 | 36 | -4 | 34 | |

| 16 | 29 | 9 | 7 | 13 | 33 | 49 | -16 | 34 | |

| 17 | 29 | 7 | 5 | 17 | 40 | 58 | -18 | 26 | |

| 18 | 29 | 3 | 8 | 18 | 28 | 62 | -34 | 17 |

What’s more, two years have now passed since a cut-off after which Sullivan is free to sell to Kretinsky or a third party without financial penalties under a clause in the rental agreement for the London Stadium.

On paper, then, there are very few barriers to a shakeup of the corporate structure and a situation wherein Kretinsky could become the controlling stakeholder at West Ham.

However, the dynamic behind the scenes is more complex – and the politics between the different ownership factions suggests that is vanishingly unlikely at present.

Daniel Kretinsky approached by other clubs as frustration with David Sullivan at West Ham builds

TBR Football Chief Correspondent Graeme Bailey has been told that Kretinsky is becoming somewhat frustrated with how West Ham is being run.

The 49-year-old diversified billionaire is unwilling to wait much longer to increase his stake and is not confident that Sullivan, 76, will walk away any time soon.

Kretinsky – who also co-owns 16-time Czech first division champions Sparta Prague – is understood to be looking at the feasibility of cashing in on his 27 per cent stake and reinvesting in another club.

Significantly, he has also fielded approaches from other teams, though it is not known how serious those advances have been at this stage.

Sources have said that Kretinsky’s profile in football finance circles has benefited from his imminent takeover of the Royal Mail.

Potential West Ham takeover bidders: Does Kretinsky have an ‘exit’ problem?

— Analysis from TBR Football Head of Football Finance Content Adam Williams.

Some critics refer to minority ownership of a club as the ‘most expensive season ticket in football.’

At West Ham, it’s a bit more complicated. Alongside Crystal Palace, they are the only Premier League side without a shareholder who controls more than 50 per cent of their club’s equity.

But there is no doubt that it is Sullivan and his chief enforcer, Karren Brady, who are pulling the strings in terms of the day-to-day operations at the London Stadium.

It’s a similar situation in some ways to what we’ve witnessed at Palace, where chairman Steve Parish is the ultimate power despite owning 10 per cent compared to John Textor’s 40 per cent.

So what is the point in owning a minority stake for Kretinsky? And, perhaps more importantly, who would want to buy his minority stake if they too are going to have little material influence at West Ham?

Ultimately, there needs to be a business plan, a pathway for that investment to be worthwhile.

After all, you need to be on the Bloomberg Billionaires Index to invest in a Premier League club these days. Those people don’t tend to invest in sport out of altruism – they want to make money.

No Premier League owners besides Man United’s Glazer family take dividends from their clubs – and even they have been forced to abandon this mechanism as the club has continued to generate losses.

Generally speaking, therefore, there are only two other ways that an owner in the current Premier League landscape can earn real cash:

- Charging interest on loans to the club or taking management fees

- Capital appreciation – increasing the club’s value and selling at a big markup further down the line

Sullivan has previously charged interest on loans to West Ham. But the figures he has earned are paltry in the context of his £1.2bn fortune. In any case, the Kretinsky money in 2021 went towards paying off those loans.

For Sullivan or Kretinsky then, the capital appreciation model is surely their M.O.

But in the latter’s case, where is the value when there are no dividends and he has limited control – relative to Sullivan, at least – of the club itself?

One view is that minority investment in a Premier League club can be a loss leader, effectively a beachhead for further investment adjacent to or outside of football in more profitable ventures.

We’ve seen this in macrocosm with Kretinsky, whose investment in West Ham has had a validating effect and has probably smoothed his route to becoming the controlling owner of Royal Mail.

But the market for minority investments in the Premier League is extremely saturated at present – Tottenham, Crystal Palace, Wolves, Brentford and Bournemouth are all seeking similar equity deals.

Macroeconomic conditions meanwhile are poor. Interest rates remain high and the markets are volatile, which will limit the pool of investors willing to enter a high-tariff industry like football.

So does the Premier League have an ‘exit’ problem? I.e. is it possible for owners or co-owners of clubs to realise the value of their investments when, broadly, speaking the clubs themselves are loss-making.

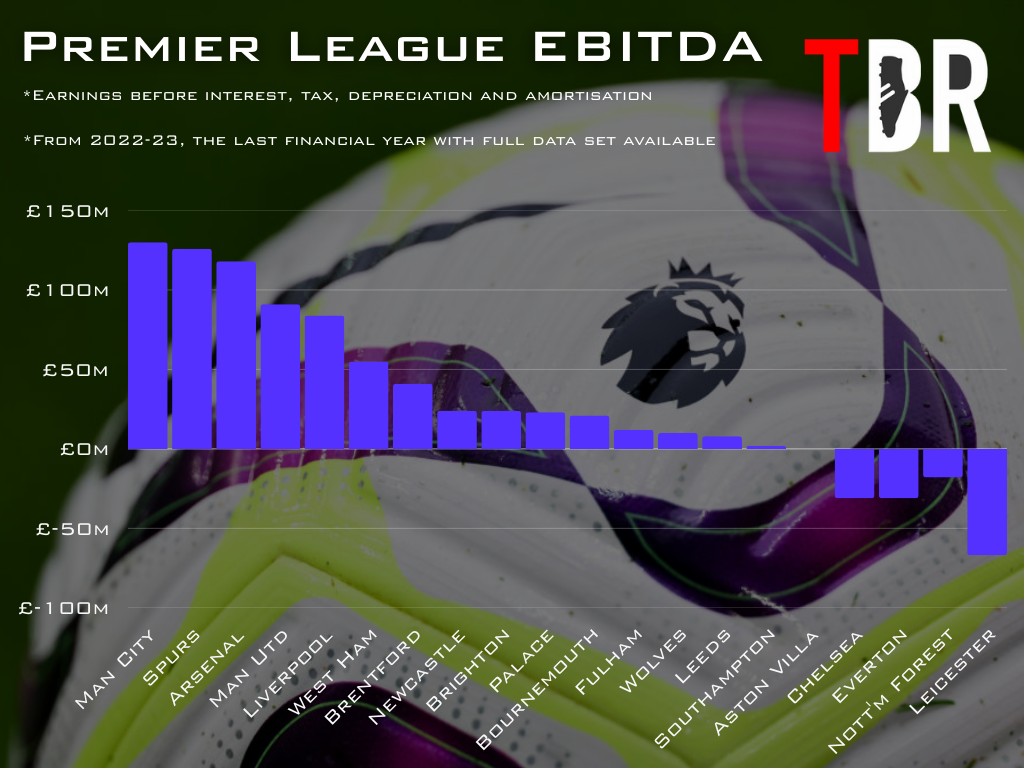

West Ham have bucked the trend in terms of generating surpluses in recent years. They posted a profit of £57m for 2023-24 and have strong EBITDA, a finance metric used to judge core business performance.

Photo credit: Robbie Jay Barratt/Getty Images

But the smart money for an investor looking to buy into sport is still in US franchise sport, where costs are are capped, revenues are stable, and profits are guaranteed.

For that to change, there would have to be a shake-up in the game’s fundamental financial structures, or an extreme cultural shift towards far, far more modest spending on wages, transfers and agent fees.

Both are unlikely, flirting with impossible.

That’s why sovereign wealth funds – QIA, who’ve been linked with West Ham in the past, or Newcastle’s PIF, for example – are one of the only options in town. They aren’t fussed about a financial return.

Until clubs are consistently and significantly profitable therefore, the Premier League M&A market is going to be relying sovereign wealth, vanity or abstruse strategic investment, or the ‘Greater Fool’ theory.

Under that model, assets are sold for bigger and bigger prices until the buyer left holding the bag at the end of the chain realises there is no real value to be had.

Karren Brady thinks West Ham are worth £800m. Others think these kind of valuations are a bubble. And what happens to bubbles when the price of a good surpasses its inherent value? They burst.