Many footballers like to market themselves as one-offs; few truly are.

Craig Johnston, however, is the exception. The Australian won five English league titles and a European Cup at Liverpool in the 1980s but his football achievements are perhaps the least remarkable thing about him.

He is an engineer and a businessman; a chart-topping musician; the creator of a television gameshow and the inventor of a hotel mini bar security system. He retired at the peak of his sporting powers, went bankrupt after investing millions in a football skills test for children in schools and is now a passionate photographer.

Advertisement

Yet ask the man himself what he makes of his extraordinary life — one that has spanned 64 years and three continents, and which surely makes him one of the most remarkable footballers who has ever lived — and he is almost blase.

“I’m interested, who knows if you’re interesting?” he tells The Athletic, via a Zoom call from Newcastle, Australia where he now lives. “Some of the most boring people in the world think they’re interesting.”

The Craig Johnston story is astonishing, and yet it almost never happened — or at least not in the way it has panned out.

The son of Australian parents — Colin, an aspiring footballer himself, and Dorothy, a teacher, who had met on a ship coming over to the UK — Johnston quickly fell in love with football, which his mother deemed a safer bet than rugby union, rugby league or Australian Rules Football.

Johnston, who was born in South Africa before moving to Australia, was a skinny child but enthusiastic and clearly blessed with a natural talent but his hopes of forging a career in the sport were almost snuffed out when he developed a serious leg condition aged six.

Initially, doctors told the family the young Johnston had contracted polio and that they would probably have to amputate his leg. It was only the intervention of a specialist doctor from the United States which prevented it: he, correctly, diagnosed osteomyelitis, a bone infection which can cause permanent damage if left untreated. Johnston had an operation and the leg was saved.

The young boy was still left bedridden as he recovered, but his time in hospital did have one positive legacy.

“It was 1966 and England were hosting the World Cup, so when I was in the hospital with my leg, that’s when I fell in love with British football,” he recalls. “I told one of the nurses, ‘I’m going to go to England and be a soccer player and I’m going to score at Wembley one day.’ She patted me on the head, laughed and said, ‘Yes, of course you are’.”

Advertisement

Johnston spent weeks on crutches but his dream to become a footballer was undimmed. Eventually, he struck a deal with his parents: if he studied hard at school in science, maths and English, then he could travel to England on his own to try and make it a reality.

Aged 14, Johnston wrote to several clubs, asking if they might consider taking him on trial. The only one to respond were Middlesbrough, who agreed to his request, so long as he covered the cost of his own flight, food and accommodation.

It was a huge undertaking for the family — Johnston says his parents sold their house and moved to a smaller one to help finance it — but, a year later, he had arrived in England’s north east with nothing to his name other than small amount of cash, a bag of clothes and a pair of second-hand football boots.

It has the feel of a fairy tale and yet there was nothing romantic about his first interaction with Middlesbrough manager Jack Charlton, who had been part of that England 1966 World Cup-winning squad and was now establishing himself as a brusque, no-nonsense manager in the Football League.

Jack Charlton (smoking) was not impressed by Craig Johnston (PA Images via Getty Images)

Johnston had started in a trial game but, after a dismal 45 minutes, found himself hauled off at half-time and publicly humiliated by Charlton.

“He said, ‘You’re the worst f***ing football player I’ve seen in my life, now hop it’,” Johnston remembers. “I said, ‘What, now?’ and he just said, ‘Yeah!’ So I picked my little bag up. I remember it was freezing cold.”

It was a bruising setback, yet Johnston said it was also the making of him. Hiding from Charlton, who Johnston admitted was “100 per cent right” in his assessment of his abilities at the time, he then spent “six or seven hours a day” practising and honing his technique in the Middlesbrough car park, while also “cleaning cars and boots for all the players”.

Advertisement

That ritual went on for the next 18 months, by which time Charlton had been replaced as manager by John Neal.

“He saw me cleaning cars and said, ‘I’m the new manager, where are you from?’ I said, ‘I’m from Australia, I’m Craig Johnston’. He said, ‘Are you an apprentice?’ I said, ‘No I’m a trialist that didn’t quite work out so I clean the cars and the boots and then I practise as much as I can’.

“One day, there was a virus at the club and they didn’t have enough players to fill the reserve team so he asked, ‘What about the kangaroo in the car park?’ And the lads said, ‘No, he’s s***’. He said, ‘Well, he doesn’t have to play, he just needs to be on the team sheet’.

“Anyway, we were getting beat so I came on and scored a couple of goals and that was my reserve-team debut. From there, things happened very fast. At 17 years old, I made my debut for Boro.”

Johnston was a hit with Middlesbrough once he broke into the first team (Mark Leech / Getty Images)

By 1981, Johnston’s progress had drawn the attention of some of England’s biggest clubs. Nottingham Forest, European champions in the two previous campaigns under the management of the irascible but brilliant Brian Clough, wanted to sign him — as did Liverpool.

“I didn’t know what to do, I was still only 20, so I phoned my dad back in Australia,” Johnston explains. “He said, ‘Forest is about a man, Clough, and he’s a very powerful man, but Liverpool is an institution’. So I signed for Liverpool, so I had to say no to Brian Clough and he went ballistic. He said, ‘Don’t you dare sign for Liverpool, you’re signing for me’. He did this amazing sell but once I’d spoken to my dad, I’d made my decision.”

It was at Liverpool — who paid a then club-record £650,000 for his services — that Johnston’s career took off. This was Anfield’s halcyon era, which saw them win 11 league titles between 1973 and 1990, together with four European Cups and a stack of domestic silverware.

Advertisement

Johnston was at the heart of it, scoring 40 goals in 271 games across seven seasons on Merseyside. With his shoulder-length curly hair and chunky jewellery, he cut a distinctive figure in midfield and became a cult hero for supporters, as well as a popular figure in the dressing room.

“It had the lovely feel of a family club when I got there but it was the Scots, and the heavy influence of Bill Shankly, that were responsible for the discipline, the behaviour, the start of professionalism,” he says. “Their insistence that training had to be so rigid and correct, it was quite amazing, and it made me grow up very quickly. I loved the craic, but it was also brutal. If you tried to be a smart arse, you were slaughtered, it was very intimidating.”

Johnston (right) with player-manager Kenny Dalglish (left) and Steve Nicol on the parade for Liverpool’s league-cup double in 1986 (Simon Miles / Allsport / Getty Images / Hulton Archive)

His favourite memories included the 1986 league and FA Cup double under player-manager Kenny Dalglish, who made him an ever-present in the starting line up after Joe Fagan’s departure.

“I scored against Everton (in the 1986 FA Cup final) and we’d beaten Chelsea the week before to win the league,” he says. “I could have died on the spot a happy man, because that was my dream as the kid in the hospital bed. It was so incredible.”

Two years later, Liverpool were back at Wembley for the 1988 FA Cup final against Wimbledon.

In the lead up to that match, Johnston co-wrote Liverpool’s official song for the game — the Anfield Rap, along with rapper Derek B and Gaye Bykers on Acid. It was designed to be a light-hearted celebration of the diversity of the Liverpool squad but proved an unlikely mainstream hit, reaching No 3 in the UK singles’ charts.

“It was a take on the dressing room and the culture of the dressing room,” Johnston explained. “Basically you’ve got two Scousers walking down the street, Steve McMahon and John Aldridge, and McMahon says, ‘Alright Aldo, sound as a pound’ and Aldo says, ‘I’m cushty, la, but there’s nothing down, the rest of the lads ain’t got it sussed, we’ll have to learn ’em to talk like us’.

“So that then goes into the Scottish accent, Zimbabwean accent, the Aussie accent, the Danish accent, the Cockney (London) accent. So the whole thing was how it was a mix of people from all over the world, all getting on with each other in what was the most successful team in the world.”

It wasn’t Johnston’s first dabbling in the music industry. A year earlier he also mixed his two favourite Liverpool chants — ‘The Pride of Merseyside’ and ‘A Liverbird Upon My Chest’ — to create a record, that was performed by singer-songwriter Joe Fagin. That only reached 81 in the charts, although the Liverbird chant has had a renaissance this season, becoming the unofficial anthem to Liverpool’s pursuit of the Premier League title.

Advertisement

After the success of the Anfield Rap, Johnston said he was asked by John Barnes, his Liverpool team-mate, to help with England’s 1990 World Cup song World in Motion, with the electronic band New Order. Johnston told how he came up with the idea to have a rap section in the song, which Barnes ended up performing. The song was a No 1 hit and is still regularly cited as one of the greatest football songs ever written.

That 1988 FA Cup final should have been one of the high points of Johnston’s career, with Liverpool dominant in domestic football and the player himself entering the peak years of his career. Instead, that game against Wimbledon at Wembley — which ended in a shock 1-0 defeat for Dalglish’s team — proved his final game as a professional player.

Johnston’s playing career ended abruptly in 1988 (Mike King / Allsport / Getty Images)

For a year, Johnston had been dealing with a family tragedy: his younger sister, Faye, had suffered major brain damage in Morocco caused by inhaling gas from a faulty heater in her hotel room.

“No one at the club knew about Faye, other than the club secretary, Peter Robinson, and Kenny Dalglish,” Johnston says. “She was having operations. I had to go to Morocco and hire a plane to bring her back to a hospital in London, and then get my Mum and Dad over (from Australia).

“So I sometimes had to miss training to go to the hospital. Faye was very similar to me, she could have been my twin, we had the same mannerisms, the same attitude in life. We all thought she’d come out of the coma and unconsciousness, that was my dream.”

Eventually the Johnston family had to get Faye back home to Australia, with Craig’s parents also needing to return to work. He went with them, which meant leaving Liverpool and quitting the sport, although it still did not ensure a happy ending.

“Unfortunately, Faye never recovered, she’s still in the same semi-conscious state,” Johnston says. “I see her a couple of times a week.”

The abrupt end of a stellar playing career would have crushed many footballers, but for Johnston it was simply the prelude to the most prolific period of his career.

As he says, “I was an inventor that became a soccer player” — specifically, of football boots, a passion project ever since those days cleaning the boots of his senior colleagues in that freezing car park in Middlesbrough.

Advertisement

“For those hours and hours in the car park, I was thinking, ‘What part of the boot, on what part of the ball, to what effect?’,” he says. “A lot of players do it instinctively and naturally because they’ve got a gift from God. I never had that, but I had the gift of problem-solving and inquisition and enthusiasm, so I figured out how to pass a ball, dribble, shoot, all that stuff.”

It was while Johnston was coaching children back in Australia that he had the idea for what became the Predator boot, one of the most iconic in the sport’s modern history.

Johnston recalls telling the kids to use their foot like a table tennis bat to get spin on the ball. They responded by saying the ball was spinning off their boots, as it was starting to rain and they were made of leather, not rubber.

“I went home and I took the cover off a table tennis bat,” he recalls. “I stuck it on my boot, wrapped it with elastic band, went in the rain and the ball squealed like a pig when the rubber engaged with the polyurethane of the ball. You could see the ball gripping and it was squealing.”

Paul Gascoigne with his Predators in 1995, complete with their rubberised grip (Gary M. Prior / Allsport)

For the next four years, Johnston spent around £250,000 of his own money developing patents and trying out different designs, before taking his prototypes to boot manufacturers Nike, Puma, Reebok and Adidas.

“They all knocked them back and said, ‘That will never work’,” he recalled. “But I knew it worked.”

Hell-bent on proving them wrong, he travelled to Munich and got German footballers Franz Beckenbauer, Karl-Heinz Rummenigge and Hans Muller to put the boots on and kick it to each other, in the snow.

He videotaped the session and took it back to Adidas, who were in financial difficulties at the time.

“I showed them the film and they went, ‘Don’t leave the room, we have to do a deal’.”

The boot wasn’t an instant hit and made little money when it launched in 1994. It only took off years later, when it was endorsed by superstars such as David Beckham and Zinedine Zidane.

David Beckham unveils his new Predator Adidas boots in 2005 (Evan Agostini / Getty Images)

By that time, though, Johnston had been bought out by Adidas. In previous interviews, including with the Daily Telegraph, he admitted this proved a costly decision as he had originally been guaranteed a two per cent share of all sales. Now, he says he would be fortunate to have even broken even from the Predator.

Johnston’s creative juices did not run dry at the Predator. He designed a second boot, The Pig, designed to give greater grip and control because of the rubber spikes running over it (‘Pig’ stood for ‘patented interactive grip’).

Its design was a hit, earning Johnston a nomination for the UK Designer of the Year award in 2004, but The Pig never made it to market.

Advertisement

“It was much more effective than the Predator in terms of getting a ball from A to B,” Johnston says. “In terms of a velocity, a sweet spot area and a swerve, it probably had twice as much control over the ball as the Predator. But it never got out into the shops. It was quite an aggressive design and Reebok (who Johnston says had agreed to take it on) didn’t fully commit to it.”

There were other ventures which had varying degrees of success. He devised a TV family game show called The Main Event, which ran for two years in Australia between 1991 and 1992, and came up with the idea for a hotel mini bar (‘The Butler’) which automatically logged what had been removed from it.

He also created a skills assessment test for children called SupaSkills, endorsed by FIFA, that he took to inner-city schools. The premise was for kids to be able to rate their abilities in various criteria — including shooting, dribbling and heading — with established players, in an attempt to keep them focused on the sport and not fall victim to crime.

Johnston ploughed millions into the project, with investors including Blur’s Damon Albarn, but despite gaining support from FIFA, it failed to secure the necessary financial funding. The setback led to him being declared bankrupt at the UK’s High Court in 2004, as well as leaving him temporarily homeless. It also led to the break-up of his marriage.

It was his nadir, but Johnston says any money he had ever earned had always been spent on his next project. His life, he admits, had been lived “on the brink”, with his passion for ideas always trumping his financial acumen.

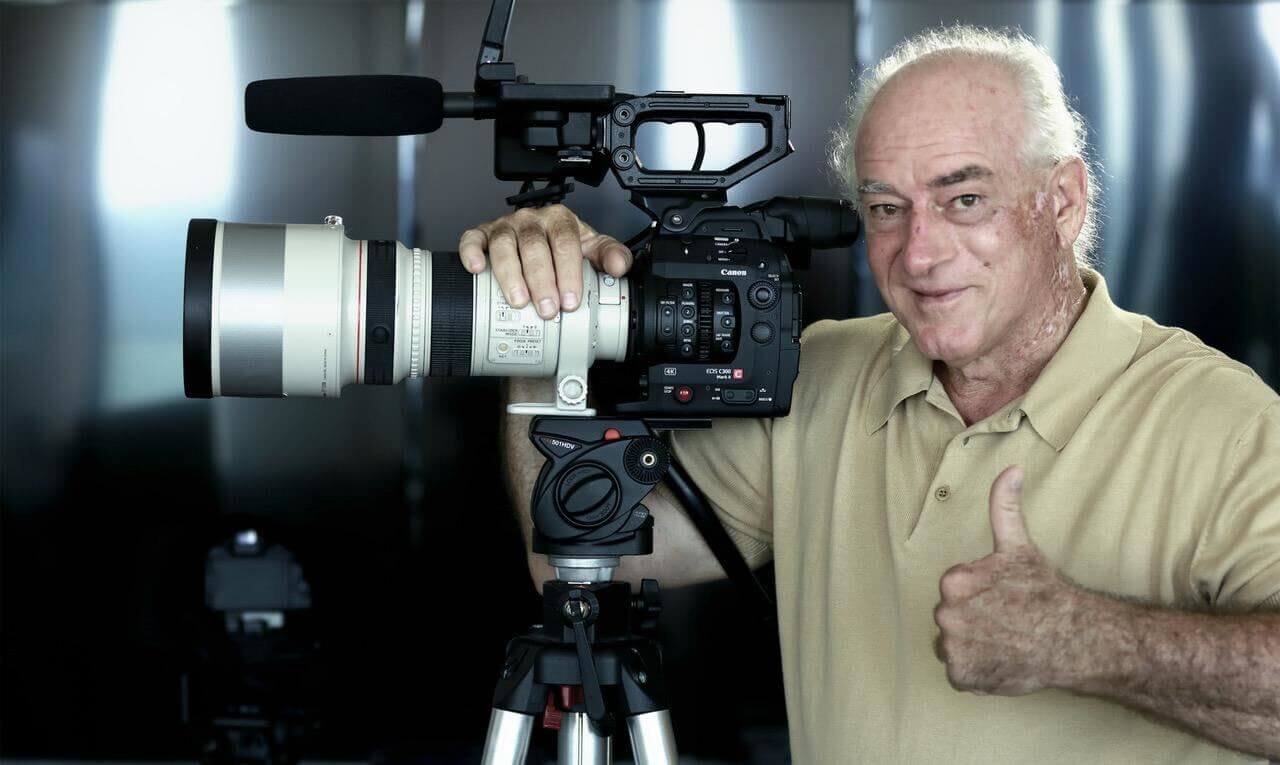

Things are more settled now. Johnston, a father to four girls, devotes much of his time to photography, another lifelong hobby, although he hasn’t left his inventing days behind him entirely: he tells The Athletic he is working on another new football boot design.

Johnston is a keen photographer (Photo courtesy of Craig Johnston)

He is not a regular visitor back to the UK but, just before Christmas, he did make an emotional return to Liverpool for the first time in 20 years, taking in the 2-2 draw with Fulham.

“It really was powerful, because when you live 12,000 miles away, you forget where you were and what you were doing,” he says. “Because where I am now and what I am doing now is so very different.

“I’m 64 years old, I’m tough, I come from a tough school. I’ll never, ever be a victim because there’s always a solution. I’ve far from given up — I’m just beginning.”

(Top photo: Courtesy of Craig Johnston)