Matt Slater joined Ayo Akinwolere on The Athletic FC Podcast’s series on multi-club ownership this week to give his expert views on a hugely important, and divisive, part of the modern game.

In the third and final episode, which was released on Wednesday, Matt answered questions concerning the topic from our listeners and readers, going into detail on the positives and negatives of multi-club networks, the financial situations at these groups and the implications for the clubs purchased as part of these schemes.

This is a partial transcript that has been edited for clarity and length. The full episode can be listened to by clicking on the link below.

And to listen to the previous two episodes, please click here.

Adam M: Leicester fan here. I can’t see any positives from our multi-club model. Our youth players go to Belgian club Leuven and never get played (Leuven don’t appreciate being Leicester’s feeder side and rightly so).

Equally, Leuven have some talented players who are coveted by Premier League teams yet Leicester haven’t leveraged the relationship to sign them. So what’s the point?

Advertisement

Matt Slater: A few years ago lots of clubs were buying a Belgian team, or a Dutch team or a French second-division team and saying they have ticked the multi-club box.

If you look for hotbeds of football talent some of the places that come up, along with Brazil, are London, Paris and Brussels. So to be in these places sort of made sense.

But when I look at that Leicester relationship, you are right. What have Leicester got out of it? I can see very little evidence of a coherent strategy or of any real attempt to maximise their footprint in the Belgian league.

There have been players that have gone there on loan, one was Kamal Sowah and I remember people had high hopes but it didn’t come to anything. He’s now playing in the Netherlands (at NAC Breda) and has got just one international cap (for Ghana).

Sowah playing for Leicester in pre-season in 2021 (Jacques Feeney/Getty Images)

He went to Club Brugge but didn’t score any (league) goals for them. So that wasn’t good enough. Now, look, that happens, recruitment is hard. But still, it’s almost like: “Is that it?”

Nathaniel F: When you factor in the initial purchase costs and the ongoing yearly profits or losses, do multi-club networks actually make money? Even if they don’t turn a profit in the short term, would their potential sale value end up being higher than those costs?

Matt Slater: The short answer is no. I think UEFA estimate that something like 350 clubs in Europe are part of networks. There may be one that I can’t think of that is turning an annual profit, but I’d be surprised. That shouldn’t shock people, though. Running football clubs is hard. Very few of them are profitable.

A good example here would be City Football Group. They’ve got 13 clubs and have been spending a fortune on them, but the total combined losses of the group is now basically £1billion ($1.28bn). And that doesn’t include the costs of acquiring some of these franchises.

Multi-club ownership has become the big idea in European football over the last five to 10 years, but it still feels unproven. I don’t think anyone has really proven it can work. The one exception, and there are caveats, is Red Bull. They could probably say it’s worked for them, but remember they are selling us drinks too. So part of their expense on the football teams is from their marketing budget.

Nathaniel F: City Football Group is led by some of the brightest minds in both football and business, so why is it that most of their teams aren’t as successful as Manchester City? You would think that teams in places like South America, New York or their various clubs in Asia would be winning more often.

Advertisement

Matt Slater: It’s about perception. Manchester City have been amazing for 10 years. Have the other clubs been as successful as them? No, but they have still been quite successful.

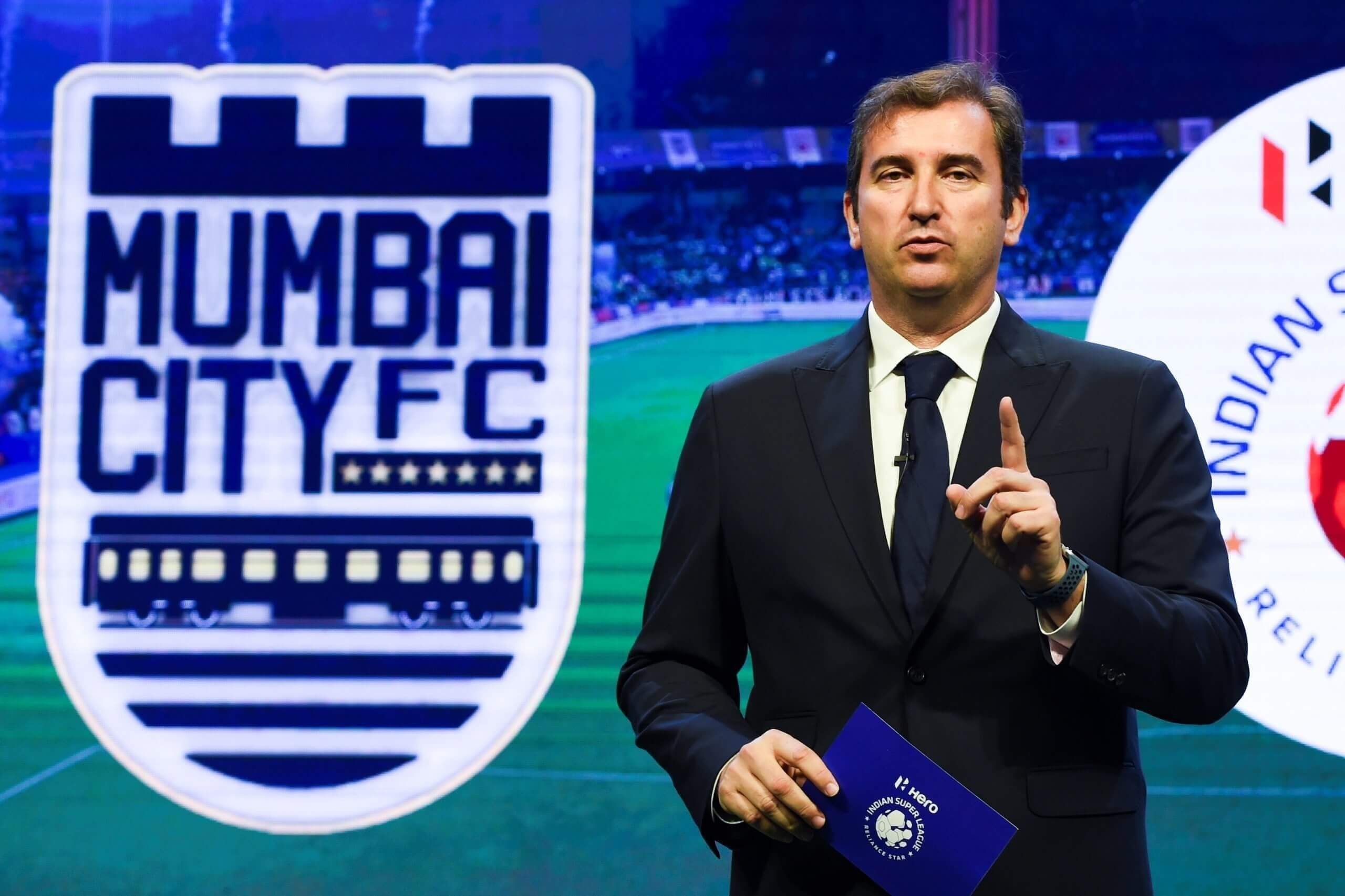

The year 2021 in particular was amazing. NYCFC won the MLS Cup, Mumbai City won two trophies and Montevideo got promoted that year.

City Football Group CEO Ferran Soriano speaks in Mumbai in 2019 (Indranil Mukherjee/AFP via Getty Images)

It hasn’t been as good for the other teams since, that’s true. But look at some of the investments they’ve made — Troyes and Lommel, for example. They were clearly bought as feeder teams. That is where they expect teenagers to get playing time in a European league and they will then see if they are good enough.

They probably aren’t trying to win everywhere, because they haven’t chosen clubs with the capability of winning as easily as Manchester City. The underlying inference is that the group is channelled to make Manchester City good. If you have a good enough player in the group, they will get funnelled to Manchester and the centre of the first team.

David S: The very concept of multi-club ownership is an abomination and the antithesis of what football should be about. We all reluctantly accept that the days of being owned by your local millionaire are done, but legislation should restrict owners or shareholders to a stake in a single football club. Multi-club ownership throws up potential for conflicts of interest and the prospect of sheer neglect towards the smaller clubs in a portfolio.

Matt Slater: It’s an unproven thesis. It feels like we are living through an experiment. How many times have I said running football clubs is hard? They are loss-making, so if you own several then you are making it even harder. That’s a concern for me.

So, 777 Partners is probably the poster boy for when it goes wrong — an American investment firm based in Miami that started accumulating football clubs for a bizarre reason. They were arrogant and they thought they could do it better. But the main guy there was called Josh Wander and he gave a notorious interview to the Financial Times where he talked about football fans being eager to be monetised.

Advertisement

And this network of clubs was a kind of great big shopping window for sponsors and credit card and insurance firms to sign up fans. It all fell apart and they have been accused of fraud. They owned Standard Liege and Hertha Berlin. They also nearly bought Everton.

We are not talking about brands of clothing or coffee, this is sport. We want our owner to really care about our club, so I totally understand where the question is coming from. But the reason multi-club ownership is happening is because the industry isn’t quite working.

Think about Trent Alexander-Arnold (at Liverpool). This is a classic case of a highly-paid, precious asset that may go for nothing due to the (club’s) own failures. If you could somehow keep that within a group, you can sort of mitigate some of that risk. So I understand.

Yet when people ask me if I would want it for my club, I usually say no. However, it wasn’t that long ago that my club very nearly shut. So if the choice is between nothing and carrying on, well then it’s like: “Yeah, okay.”

I’m afraid I am sitting on a fence here, because I can see where the multi-clubbers are coming from. I look at the industry and see failing businesses, distressed assets and jobs at risk. So I’m thinking: “Well, I’m not surprised that people are thinking ‘let’s consolidate and try and be sustainable’.”

Ayo Akinwolere: Fans are powerless to a certain degree about the people that take over their club. For instance, if you’ve got a club that was close to administration not too long ago then many fans are thinking: “OK, yes please.” But very few have looked down the line to see whether or not this is a legitimate group or whether they have the right ethos for the club.

Matt Slater: This is so big. As fans, you can get organised and you can make it uncomfortable (to try and get) someone to leave. What you can’t really do is do the vetting and do the choosing (of prospective owners).

It’s really still (down to) that owner to sort of choose their successor. This is the situation at Reading, Swindon and Morecambe. It’s really hard and you feel powerless.

Swindon Town’s stadium — The County Ground (MI News/NurPhoto via Getty Images)

Michael H: Previously when this topic has been spoken about on The Athletic FC Podcast, it has been negative and multi-club ownerships have been viewed as an existential threat to football. Has that view changed? Is there an acceptance that they are here to stay?

Matt Slater: Yes. It’s here and it’s not going away. The game has got to, I think, have a clearer idea around separation and how we police this, because it does seem a bit ad hoc at the moment.

Advertisement

Is anyone really making money yet? Not yet. Is anyone getting sustainable? Yes, I think some are probably close to sustainability. Are any starting to really kind of hit their goals? Black Knight appeared to be getting close to hitting their goals and there are a few others out there that would probably say their goals are about one or two of their teams being really successful.

You can listen to other episodes of The Athletic FC Podcast, which covers the biggest issues and talking points in the game, here.

(Top photo: Manchester City’s CEO Ferran Soriano (left), manager Pep Guardiola (middle) and chairman Khaldoon Al Mubarak (right) with the Champions League trophy in 2023; by Michael Steele/Getty Images)