In the kitchen of Joachim Zadow’s Wirral home, the retired architect is reminding himself of the features in the “dual stadium” that may have been hosting Wednesday’s Merseyside derby had Everton and Liverpool embraced his ideas in the summer of 2010.

“The concept works,” insists Zadow, 15 years after playing a key role in a plan that culminated with 27 pages of his design being presented to Everton before they were shipped to the United States for the consideration of Tom Werner, recently installed as Liverpool’s chairman following Fenway Sports Group’s takeover.

Advertisement

Liverpool ended up remaining at Anfield by rebuilding two stands, while Everton’s future has dragged on, with a move to a new dockside venue scheduled for the start of the 2025-26 season.

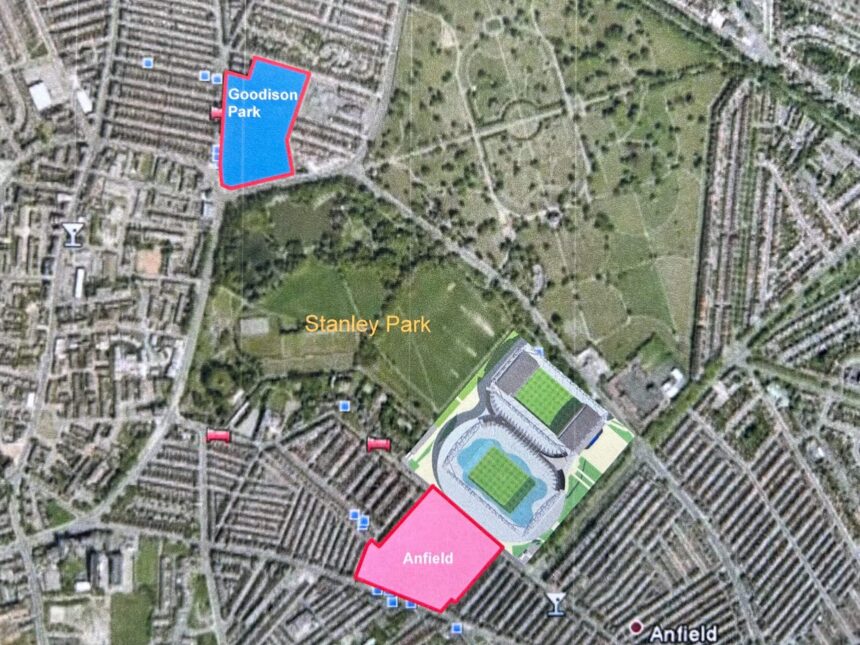

Zadow’s vision placed both clubs on the same Stanley Park site, with two stadiums joined by a 10-level central hub with space for a hotel overlooking each of the pitches.

The proposed location of the joint stadium in relation to Goodison Park and Anfield (Joachim Zadow)

The project was very much of its time. Zadow and the other members of the “Mersey Stadia-Connex” group believed they had come up with a cost-saving solution to Everton and Liverpool’s problems because the clubs were looking for exit routes out of Goodison Park and Anfield, and both were struggling financially.

During the 2009-10 season, Everton’s move to a new site in Kirkby was halted by the British government following a public enquiry amid fierce opposition. Meanwhile, Liverpool lurched towards economic catastrophe, with Royal Bank of Scotland raising doubts on two occasions within the space of a year about the club’s ability to continue.

Liverpool’s immediate problems had been caused by feuding owners Tom Hicks and George Gillett, whose leveraged buyout in 2007 was followed by a global financial crisis. Beneath that broken relationship was the stadium issue: like Goodison, Anfield was hemmed in on all sides by terraced housing.

Manchester United were the club to beat and their matchday revenues from Old Trafford were more than double that of Liverpool’s. Hicks and Gillett had made their own plans for a venue at Stanley Park to try to bridge this gap, but Hicks’ promise for a “spade in the ground” inside 60 days was never kept.

Three years later, Liverpool’s position worsened by the team’s failure to qualify for the Champions League for the first time since 2003. In the same month, Rafa Benitez was sacked as manager just one season into a five-year contract.

Advertisement

Under such uncertainty, Zadow and the other members of the consortium shared their proposal with the local Liverpool Echo newspaper, albeit without any of them going public about their own identities. The decision led to the plan being described in a headline as a “Siamese stadium” as well as online speculation about whether the shadowy group was linked to a takeover of Liverpool, with one of the rumours stretching as far as interest from the Chinese state.

It is only now that Zadow feels comfortable revealing his part.

“It felt like both clubs were trembling,” he recalls. “They were at a funny stage of their histories. What we did was totally speculative but we felt like we delivered a compelling plan. If the clubs embraced it, then we’d have probably come forward — but it never reached that stage.”

Joachim Zadow with his design (Simon Hughes/The Athletic)

The Athletic was able to establish Zadow’s involvement by following an online trail. He agreed to speak after consulting Andy Heron, the group’s leader, who also lives on the Wirral.

“It was an independent project,” Heron says. “There was no connection to any interested buyer of Liverpool, despite the rumours. Everyone involved had professional connections to Merseyside and that brought a certain spirit. There was a mix of Liverpudlians and Evertonians. We were interested in the prosperity of both clubs and by extension, the city. Admittedly, if the project moved forward, we’d all get paid but, unfortunately, that never happened.”

Heron had grown up a Liverpudlian, living near Calderstones Park in Allerton, before becoming a roofing contractor and a small property investor. “I hadn’t worked on anything like this before,” he admits, though he knew how to tend for contracts. “I estimated that we had a five per cent chance of it leading somewhere.”

Heron says he was brought up on a spirit of cooperation existing between the clubs and their fanbases. He cites ‘Merseypride’ banners at cup finals between the teams in the 1980s as evidence of this. “It stayed with me. I hoped it might still exist.”

His family were also rugby league supporters and his connections with Widnes helped open a door at Everton. Heron says that during a telephone conversation with a high-ranking official, it became clear to him there might be an opportunity because “everything was on the table” following the collapse of the Kirkby plan.

Heron was thinking of a “mega stadium” that would save Everton and Liverpool hundreds of millions of pounds. “In my mind, it was a colossal thing, but it was also an enterprising solution for each club,” he says. “As far as I was concerned, it wasn’t just a pipe dream.”

Everton will play in their new home at Bramley-Moore Dock next season (Christopher Furlong/Getty Images)

Heron knew a consultant structural engineer with contacts that could help him. One of them was Zadow, who had settled in the area after moving to Liverpool from Stockport in 1960 to complete a degree in architectural studies. Locally, Zadow had worked on small projects but abroad, there were bigger ones, including the design of a suburb on the outskirts of Jeddah where 3,377 houses were built. He later designed a hotel in the Saudi Arabian port city.

Advertisement

By 2010, Zadow was in semi-retirement. He confesses that he is not really a football fan but if he supported one team, it would be Liverpool. “I had no work at the time and thought, ‘What the hell, I might as well do something…’.” His email chain with Heron began in March of that year and following a meeting at Heron’s house, they agreed to try to come up with something. This involved Zadow getting his hands on the planning documents for the stadium that Hicks and Gillett failed to build.

After looking at several potential sites, including the north Liverpool docks where Everton will move into later this year, Zadow realised that the only viable option for something of this scale was Stanley Park, given it already had planning permission. “As long as I stayed within the red lines, I thought it gave us a chance,” Zadow reflects. “Once you go back to planning, it slows everything down.”

Using modelling software and a rendering programme, Zadow came up with a 60,000-seater stadium for Liverpool and 50,000 for Everton. The latter would be multi-functional, with a closable roof and a pitch that rolled away.

Zadow’s vision for the Everton area of the dual-stadium design (Photo: Joachim Zadow)

They would be located in what was the car park of the green space, with entrances for both venues facing Arkles Lane. Everton would be to the north, flanked by Priory Road, making them closer to Goodison, while the new Anfield would be over the road from the old stadium, albeit with a pitch rotated by 180 degrees.

How the Liverpool pitch may have looked (Photo: Joachim Zadow)

Zadow regrets never visiting Anfield or Goodison, but reasons there was no budget to play with. Initially, he had designed a two-tiered Kop grandstand before he was encouraged by another member of the group to make it a continuous one.

There was room for independent changing rooms and underground museums. Yet the “clever bit”, according to Zadow, was the shared facility in the middle, which not only saved money but, in theory, could stimulate additional revenues through 300 hotel rooms, some of which had windows facing each of the pitches.

“It seemed logical: Everton here, Liverpool there,” Zadow says. “Fans get into the habit of going to the same place. This would have kept both clubs close to its roots and the fans, their routines.”

Advertisement

Heron says that a meeting with Everton went well but he was struggling to get in front of people at Liverpool after copies were sent to the club’s offices. On reflection, he thinks maybe the timing was wrong because both owners wanted to sell up and nobody involved at Liverpool was really in a position to commit to anything.

This led to him floating the idea in the Liverpool Echo, without giving away too much because Heron was concerned someone might steal the idea. “The ‘Siamese stadium’ was a media tag. It certainly wasn’t a term that we used,” Zadow says.

The report that followed was published just three days after it was revealed for a second time in 12 months that the Royal Bank of Scotland was concerned about Liverpool’s future. While a Liverpool spokesman told the Echo: “We remain committed to building our new stadium in Stanley Park,” an anonymous source at Everton suggested the scheme was “unworkable, unaffordable and undeliverable”.

Liverpool have expanded Anfield’s capacity past the 60,000 mark by redeveloping the Anfield Road Stand (Robbie Jay Barratt – AMA/Getty Images)

The Echo’s reporting led to a significant public response. In the same month, Well Red, a Liverpool fanzine, led with the headline: “Could we twin and bear it?”. For some Evertonians, the answer was no because the size of the stadiums, despite room for an increase in capacities, put Everton at a disadvantage straight away.

Ultimately, for both clubs, the same problem remained: who would finance all of this? Peter McGurk, another local architect who had come up with plans to redevelop Anfield, suggested any new stadium would cost just as much in debt or return to investors as it would add to existing revenues. “Fans would be pouring more money into the pockets of banks or owners with no additional help for the team,” he told Well Red.

Heron knew that even if he got both clubs to agree to the move, the next step would be convincing Liverpool City Council and passing a feasibility study. Meanwhile, Zadow can laugh about it now, but he remembers some of the online comments about his design being particularly cutting. “They were saying it looked ugly and it made me feel bloody awful, but I just didn’t agree! I still don’t think it looks ugly!”

Heron was almost at the point of giving up but when Liverpool were taken over by FSG five months later, he had one last go at engagement. This involved him finding the address of Liverpool’s new chairman, Tom Werner. “I sent him the proposal by recorded delivery. It was signed for but we never heard back.”

Advertisement

Zadow knew that the odds were always against him but he wishes they at least came closer to fruition. “I relished being a part of something that had never been attempted before but I thought it was a winner. Of course I was disappointed that it didn’t end that way. I might have been a millionaire!”

(Top photo: Joachim Zadow)