Nicola Raccuglia does not need a second invitation to cycle through his memories. His voice is so soft now that it is little more than a whisper, but he tells each story with a practised air. He has repeated them so often, lived in them for so long, that he embarks on them almost instinctively; they are, he assumes, what everyone wants to hear.

Advertisement

They are, make no mistake, good stories. Really good stories. The cast list, in particular, is dazzling. There is one about Diego Maradona recovering from a training session at Napoli by opening, and quickly finishing, a bottle of champagne. There are others in which Maradona calls, late at night, urgently requesting Raccuglia’s help in sourcing dozens of shirts.

There is one about going into business with Johan Cruyff and his brother, Henny; one about the “exquisite” manners of Gigi Riva, the great idol of Italian football in the 1960s and ’70s; one about providing equipment to a football team comprised of Formula 1 drivers, led by the legendary Michael Schumacher.

Raccuglia still treats each of their names with reverence; even after all these years, the memories are still laced with wonder, as if he cannot quite believe that all these things happened to him, a journeyman player from Sicily who, somehow, ended up being treated by Diego Maradona, the player he regards as the finest of all time, as an equal.

Humility demands, of course, that when he tells the stories, he places the more famous names front and centre. But that framing is not quite accurate. Maradona invited him to training. Maradona offered him the bottle of champagne. Maradona called him late at night, asking for assistance. Like the others, Maradona treasured his relationship with Raccuglia just as much as Raccuglia treasured him.

“It was a special friendship because I never asked anything from him,” Raccuglia said. “Not even a photo. We never used his image for anything.” During Maradona’s troubled, triumphant years in Italy, he was one of just a handful of people who were not constantly trying to extract something from the most famous footballer on the planet.

(Getty Images)

If anything, in hindsight, it may have been the other way around. Maradona, like many other players of his generation, doubtless appreciated that Raccuglia was not primarily concerned with what they could do for him.

But they knew, too, that he could do plenty for them. For more than 20 years, after all, Nicola Raccuglia was the man who made all of them, and Serie A as a whole, look good.

The headquarters of NR, the brand Raccuglia established more than half a century ago, occupies a modest, two-storey building on the outskirts of Montesilvano, a sleepy town a few minutes north of the Italian city of Pescara. The setting is essentially suburban, unremarkable. There is a gas station across the road. There is a pharmacy next door.

Advertisement

Behind the tinted glass door, though, the scale of NR’s influence is clear. Although in theory this is the company’s office space, it feels like a showroom, more than anything; the aesthetic has more in common with a modish streetwear boutique, the sort of store that might use the term “pieces” instead of “t-shirts”, than it does with the world of printers and meeting rooms and accounting departments.

(Roberto Salomone for The Athletic)

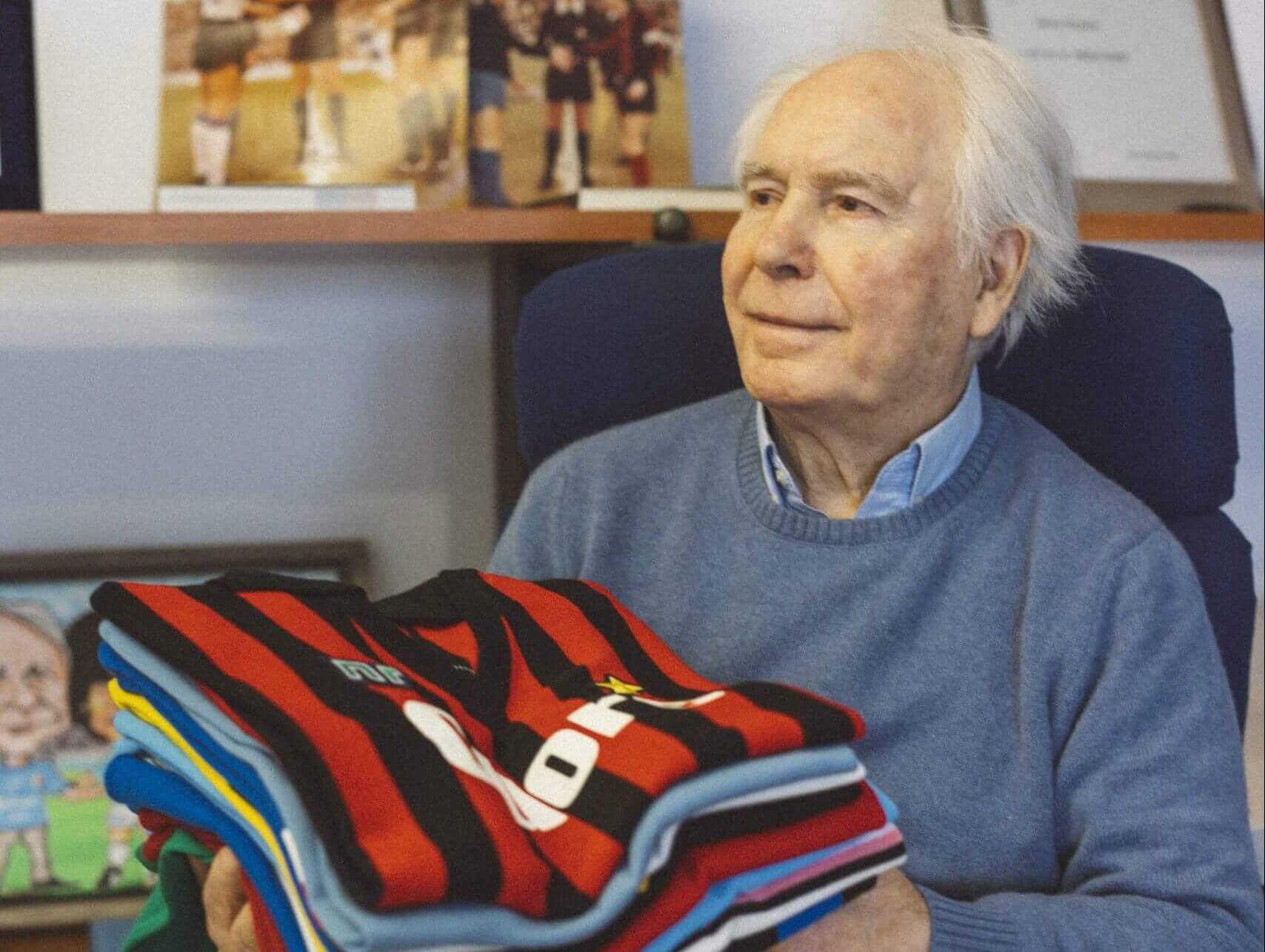

There are a handful of mannequins, each wearing a football shirt in a bold, primary colour; other jerseys have been artfully folded and displayed neatly on shelves, their crests and the sponsors visible; a dozen or so more have been carefully, lovingly draped on hangers, the rack sufficiently sparsely populated that each one has plenty of room to breathe.

Each one is instantly recognisable, not just to fans of a certain vintage but to anyone with even a passing interest in football history: the Napoli jerseys in which Maradona lifted the Serie A title, one bearing the logo of Mars and the other that of Buitoni; the sun-drenched red of Roma, embossed with the word Barilla; the deep blue of Sampdoria, tied in a bow of white and black and red. There are glimpses of the red-and-black stripes of AC Milan, and the blue-and-black of Atalanta; the brilliant yellow of Parma, the soft pink of Palermo, the senatorial purple of Fiorentina.

(Roberto Salomone for The Athletic)

These were the shirts of Serie A in its imperial phase of the 1980s and early 1990s, when it was the richest and most glamorous and most powerful league in the world. They were the shirts worn not just by Maradona but by Careca and Claudio Caniggia and Gianluca Vialli and many others, too, the ones that made Italian football seem so vivid and bright and stylish.

And all of them came, ultimately, from Raccuglia’s imagination. A journeyman midfielder, he spent much of the 1960s playing for Pescara, Vicenza and Ascoli — all three of them Serie A makeweights — before retiring in 1968.

Advertisement

He had, he said, “always been fascinated by clothes”. He had often found the kits he had played in to be heavy, uncomfortable and, above all, somewhat drab; he felt sure he would be able to do better. His playing career had left him with an abundance of “personal connections”, the sort that might be leveraged to get a start-up company off the ground.

Caniggia at Atalanta and Vialli at Sampdoria (Getty Images)

“He has always been able to create networks,” said Nicoletta Giammarino, one of his key adjutants at NR. “He can be as sweet as honey.”

That helped, at the start, of course: one of the company’s first clients, Cagliari, came about because of Raccuglia’s relationship with Riva, the club’s greatest player. What ensured NR’s success, though, was the standard of what Raccuglia was producing.

“They made everything in acrylic for the first time,” said Enzo Raccuglia, Nicola’s son. “It was all made in Italy, done by hand. The material was the best quality. It was all totally original, quality-controlled.”

And then, of course, there was the design. Nicola Raccuglia is a little fuzzy, now, on exactly what inspired each of his flourishes. “I was interested in clothes,” he said. “I was friends with actors and actresses. I tried to incorporate ideas from clothes that I liked.”

But his attention to detail, even now, is apparent: his designs were so exquisite that the magazine Sport di Piu has described him as the “Caravaggio of jerseys”. He was limited by the traditional colours of each of the clubs he worked with; sometimes, he said, they would give him instructions on what, exactly, a shirt should look like. Other than that, though, he had free rein: the embellishments, the ornamentation — centralised logos for Fiorentina and Venezia; the fine detail of Sampdoria’s rings; Lazio’s stylized eagle —were all his.

(Roberto Salomone for The Athletic)

The impact was pronounced; for Italian teams, having an NR kit became the gold standard, something approaching a mark of status. At one point, the company was providing shirts for 14 teams across Italy’s top two divisions; it was selling replicas in 700 shops across Europe, including those owned and operated by the Cruyff brothers. It was turning over somewhere in the region of 15 billion lire a year; its central factory, in Pescara, employed some 150 people, with dozens more elsewhere on the production line.

Advertisement

It had contracts with the national teams of Uruguay and the Ivory Coast, and provided kits to the New York Cosmos thanks to the recommendation of Giorgio Chinaglia, the team’s firebrand Italian striker. When Raccuglia met Maradona, the pair of them toasting each other with champagne, they were both stars in their own fields; both had done their part to burnish the image of Serie A.

NR’s success, though, was also in some ways the root of its demise. As Italian football — football as a whole, in fact — grew more popular, companies far larger than NR saw it as an opportunity. “Once the big international companies came in, we could not compete,” said Enzo Raccuglia. “We’re a family business. They were able to offer more money, and because they were not making everything in Italy, to do it at a lower cost.”

(Roberto Salomone for The Athletic)

Slowly, surely, the clubs moved away, either to Italian brands Lotto and Kappa, or to Adidas, Umbro, Puma. NR shifted its focus to its other business, providing bulk kits for semi-professional teams. The days when it had dressed the greatest stars in the game were consigned to memory, the shirts that had once graced the pitches of Serie A now worn only by those mannequins in NR’s office, a silent gallery of Raccuglia’s genius.

Raccuglia is 85 now and not quite as spry as he once was. He had a back operation this year, and he is feeling the strain of the physiotherapy sessions designed to get him back on his feet.

(Roberto Salomone for The Athletic)

None of that, though, has stopped him from working. He still comes into the office most mornings. He still likes to be involved in “every step of the process”, as Giammarino put it, from selecting the colour of material before it is ordered and checking its quality once it arrives. “He is a perfectionist,” she said, even if he is one who tends not to come back after lunch.

Long after it stopped producing shirts for Italy’s elite teams, NR is undergoing an unexpected, but overdue, revival. “We always had requests to start producing shirts again,” Nicola Raccuglia said. “They came from people who remembered the shirts, the ones from their childhood, but found it difficult to get hold of them.”

In recent years, those requests started to come in ever greater volume. Neither Nicola nor his son are entirely sure what inspired it; it is a mix, they believe, of a “nostalgia” for that period, the rise of vintage football shirt culture, and the ability of social media networks, particularly Instagram, to diffuse all of that to a new generation.

Whatever the cause, NR eventually received enough requests that it was obvious there was demand for their jerseys. “We have been making them again for five or six years,” Enzo Raccuglia said. “We make them in exactly the same way as we used to: everything is made in Italy, everything is made by hand.”

(Roberto Salomone for The Athletic)

The authenticity runs deeper than that. NR is using the same machines and, in some cases, the same staff to make shirts in 2025 as the company did in 1985. “The guy who puts the numbers on the backs of the shirts is the same one who did it back then,” Giammarino said. “We have some of the same seamstresses who sewed them before, too.”

Advertisement

The work is slow, painstaking: the club crest, the sponsor, the numbers on the back all have to be aligned by hand. “If they’re so much as a millimetre out, you can tell,” said Giammarino, who does some of the work herself. “It is very precise, very skilled, and it takes a long time.” To produce a batch of 90 shirts, from start to finish, it takes around three months, she said.

That makes them much more expensive, of course, but it is also what makes them so appealing. “You can feel the love in the production,” Nicola Raccuglia said. “You can feel the love that has gone into each one.”

(Roberto Salomone for The Athletic)

Seeing them in NR’s office they do not seem like mere items of clothing, inherently disposable, profoundly utilitarian. They have little in common with most modern shirts, swapped out every season, discarded in favour of something new after only a few months of their existence.

They are more lasting than that: they are memories, or springboards to memory, portals in time; they are immediately evocative of a period not just in football but, for fans of a certain generation, of a time in their own lives. They are closer, really, to works of art, ageless and timeless, a selection of masterpieces lovingly curated, still, by the man who gave Italian football its sense of style.

(Top photo: Roberto Salomone for The Athletic)