“Lying gives flowers but does not bear fruit,” wrote Fenerbahce’s on-loan winger Allan Saint-Maximin on an Instagram story last month after his manager Jose Mourinho accused him of being overweight.

The words appeared beneath a screenshot of the former Newcastle United player’s body composition measurements, which showed his weight (84kg) in March matched his weight in 2022 when he was a starter for Newcastle — and was 1kg lighter than when he was starting for Fenerbahce in 2024.

Advertisement

The discord between player and manager was prompted by Mourinho leaving Saint-Maximin out of his squad to face Rangers in the second leg of their Europa League last-16 tie in March, after which the Frenchman posted on Instagram, “It will take more than this to defeat me. When a lie takes the elevator, the truth takes the stairs. It takes longer but it always arrives in the end.”

When asked about Saint-Maximin’s message, Mourinho responded in typically sardonic fashion: “When a football player works well, works hard, trains every day, he is fit and can climb the stairs. He doesn’t need an elevator. However, if a player doesn’t train well, arrives late, is overweight, is not ready to play, he needs an elevator to go up. Because he gets tired quickly on the stairs.”

Of the four slurs hurled his way, it was the one referring directly to his bodyweight that Saint-Maximin refuted most specifically. Perhaps because it’s the one most easily disproven. But it’s also the one that is likely to sting the most.

Allan Saint-Maximin with Jose Mourinho in December (Burak Basturk/Middle East Images/AFP/Getty Images)

It’s a feeling Ipswich Town midfielder Kalvin Phillips knows well. When he returned to his former club Manchester City after making two substitute appearances for England in the 2022 World Cup, Phillips was left out of Pep Guardiola’s squad for their first match back. Explaining the player’s absence to the press, the City manager said the midfielder had returned from Qatar “overweight”.

While Phillips did not dispute that he had come back 1.5kg over his weight target, he felt Guardiola could have gone about addressing the issue in a “different” way. It was, said Phillips in an interview just over a year later, the “toughest” period of his rollercoaster time at the club and eroded his confidence.

“Being told you’re overweight in front of national media… how would that affect you?” asks sport nutrition consultant Dr Nessan Costello, who has worked as a consultant for Premier League and Championship clubs.

Advertisement

“They are human beings, first and foremost. They’re exposed to so much external noise, and while they’re far better at handling it than most of us, it still takes a toll — no one is immune to that.”

Costello believes football has an “outdated fixation” with body composition (how much of a player’s body is fat, bone and muscle mass) as a performance metric. In January this year, he wrote an impassioned plea on Substack for his fellow practitioners to stand up to “outdated practices and redefine what high-performance nutrition support looks like in the men’s and women’s professional game”.

The tipping point? When yet another high-level football club hired him “for the sole reason that they thought they had fat players”. When Costello arrived, he discovered a team in excellent shape “as you would expect for people who are professional athletes, highly motivated, and judged at every turn,” he tells The Athletic.

Exercise-based ‘punishments’ and publicly shared leaderboards are often used when tracking players’ weight or body fat percentages, which, according to Costello, can create a “culture of fear, where players are judged on their physical appearance rather their football performance.

“Sometimes, managers ask for body-fat measurements every week. I’ve even been told that my sole job is to measure body fat, because ‘I want my players to look like athletes’. In many cases, nutrition practitioners are brought in purely to provide body composition assessments. It’s a classic case of Goodhart’s Law: when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.

“We’ve lost sight of the nuance between body composition and on-pitch performance, because it’s been reduced to a single number.”

Pep Guardiola commented publicly on Kalvin Phillips’ weight (Adrian Dennis/AFP/Getty Images)

And that focus on numbers can lead to the individual being slightly forgotten: “Often players aren’t even involved in the decision-making process when it comes to their own bodies,” says Costello.

His experiences are echoed by a performance nutritionist who has worked for Premier League clubs. Speaking on condition of anonymity to protect relationships (we’ll call him performance nutritionist A), he says, “Often there’s just a number that’s the club’s standard and everyone has to comply with it. There’s rarely any open discussion between a practitioner, coach and player about what we’re doing, how we are doing it, and why we are doing it.

Advertisement

“It could be: ‘We feel you could gain from getting another few centimetres when you go up to head the ball’. Or: ‘You’re lacking speed and we know, because of power to weight, that by taking 2kg off you, that’s going to give you greater speed’. When those decisions are made as a multi-disciplinary team and everyone’s involved and empowered, the player can’t help but feel supported. But nine times out of 10 it’s not, it’s just a load of numbers on a page and people getting told, ‘That number’s not good enough’ but without any reason why.”

He describes nutritionists watching players eat in the dining room and asking them to write down their intake. “Players just feel like they’re being spied on; that they’re not trusted,” he says. “But that’s the expectation now. It’s all about quantifying athletes. The heads of sports science and heads of department want a report on what every single player is eating every day of the week. It’s just not healthy. And it’s not the way I like to work: I like to empower my players, educate them and make them independent.”

There is also the matter of how much difference it makes. James Morton, professor of exercise metabolism at Liverpool John Moores University and former head of nutrition at Liverpool FC and ex-nutrition and physical performance lead at Team Sky (cycling), believes the effect of body composition and weight management in football has probably “been overinterpreted over the years”.

“Football is a skill-based sport,” he says. “It’s not often determined by weight, it’s determined by skill. Yes, if someone is too heavy or too light then you might not be able to actually deliver the skills that you have in the first place, but I think it often is overinterpreted. The evidence supporting changes in body composition and football performance is nowhere near as established as it is in other sports.”

There are various ways to measure an individual’s body fat. The most common method in elite sport is a skinfold assessment (pictured top), whereby a practitioner will use callipers to pinch the top layers of skin and measure the subcutaneous body fat (the fat just underneath the skin) at specific sites on the body.

The gold-standard approach is set out by the International Society for the Advancement of Kinanthropometry (ISAK), which measures eight sites, using the sum to indicate body-fat levels, which can be tracked over time. Some people convert this into a fat and fat-free mass (muscle and bone) percentage using predictive equations, but the raw sum is more accurate and typically preferred. However, it is not perfect.

“The first issue is the accuracy of the measurements, which is not that good,” says Dr James Malone, a football scientist and consultant who was a first-team sports scientist at Liverpool from 2010 to 2013. “There’s a variety of experience when it comes to measuring body fat. People who do that job are supposed to have an accreditation from ISAK but in practice I know there are people without that accreditation who are taking these measurements and potentially giving false data.”

Advertisement

One recent job advert for an academy nutritionist at a Premier League club had “conduct regular body composition assessment with the U18 cohort” as a key responsibilities, with an ISAK Level 1 accreditation listed as essential. This can be gained on a two-day course.

Even if the practitioner doing the testing is vastly experienced, results can still be off, says Costello: “Individuals naturally differ in skin pliability; the ease with which an accurate skinfold pinch can be taken, which can significantly influence body composition readings. Genetics and somatotype both contribute, meaning some athletes may consistently score higher or lower based on these factors alone.”

DEXA scans are another method of measuring body composition, one considered more precise for tracking the distribution of fat, muscle and bone within the body. The machines look similar to an MRI scanner and often used within the NHS to assess bone density. They need qualified professionals to interpret the data, but an increasing number of top clubs are using them.

However, skinfolds remain the most common method for now, with some clubs testing every four weeks or more, far more frequently than at GB Boxing, where the nation’s best amateur boxers train and weight is crucial, yet testing is only done three or four times a year.

“It’s just collecting data for the sake of it, because they feel like they should,” says performance nutritionist A of football’s data addiction. “I’ve had data that’s a couple of weeks old and I’ve been asked for an update. You’re wasting everyone’s time and are actually going to reduce players’ confidence in the data because they’re going to be looking more at ‘noise’ within the data rather than actual changes.”

The potential negative impact of fixating on body composition is considerable. Last year a study led by players’ union FIFPRO found that one in five professional female footballers experienced disordered eating over a 12-month period, something Arsenal and England striker Alessia Russo spoke about in 2023, describing a “low point” during the first Covid-19 lockdown when she tried to lose weight.

“There’s a bit of a stigma because, of course, you want to compete and be the best on the pitch, but you want to look a certain way as well,” she told Women’s Health magazine. “I wanted to be skinny and compete at that kind of level. (Now) my body is still a huge priority, but I understand I need to eat a lot more than I thought I did at the start, and now I don’t want to be skinny, I want to be strong.”

Alessia Russo felt pressure to by “skinny” (Justin Setterfield/Getty Images)

There have not been many studies on disordered eating or body image issues in the men’s game, possibly based on the misconception that such things are inherently ‘female issues’. But those working within the game are in little doubt that male players are affected, especially in an age when social media adds more noise and pressure than ever before.

Advertisement

“Players are typically very conscious of their body shape, size, and weight,” says Costello. “Like anyone, they want to look and feel great, but they also face the added pressure of performing at the highest level of their sport. It’s not uncommon for them to view their ‘super strengths’ as weaknesses. Rather than appreciating the value of their additional muscle mass, they often strive to look and weigh the same as everyone else. This can lead to maladaptive behaviours like skipping meals, fasting or following extreme diets.”

Costello describes coming across players who were labelled “fat” in academy systems as teenagers and remain “scarred” by those early experiences. “These players are still deeply affected,” he says. “I’ve heard things like, ‘I can’t eat this, I can’t drink that’, or, ‘My weight has to be X or I won’t be allowed to play’. Some weigh themselves multiple times a day; before meals, after meals, even before going to bed to ensure they stay within a prescribed number. It’s a problem entirely of our own making, and one that players are paying for.”

A 2024 study found that the day before a game, 81 per cent of players in one Premier League club were not meeting recommended sport nutrition guidelines for the amount of carbohydrates needed to fuel them for a game. Costello was not surprised. He notes a widespread “fear of carbohydrates” among players, often driven by aesthetic pressures and misinformation.

“I’ve seen players during sessions feeling light-headed or faint; they’re hypoglycaemic because they haven’t fuelled properly beforehand,” he says. “A lot of that stems from a desire to look a certain way, or from societal myths that carbohydrates make you fat or that sugar is inherently bad for you.”

“The current culture is that everyone has to have these ripped bodies and six packs,” says Malone. “We had players at Liverpool who would go on low-carb diets just to look good. What we typically say is that, in the days leading up to games, they should really be hammering the carbs. However, what we’ve found from surveying and other studies is that they’re actually under-fuelling going into games.”

Malone says that restrictive behaviour around eating would typically be seen more widely at this time of the season, with players bound for warmer climates in the summer and wanting their physique to stand up to public scrutiny. “We also then see them doing more bodybuilding-type stuff in the gym to look good,” he says. “It sounds ridiculous but it does happen.”

Last year, a research paper by Morton and PhD student Wee Lun Foo from Liverpool John Moores University was published, looking at how male footballers perceive the nutrition culture within the professional football environment, including their views on body composition. “It came from the coaching staff… You just had to be low (in body fat),” said a participant. “It is just a broad thing that lower is better… I think high body fat is often perceived as you are eating bad, or you are lazy.”

Advertisement

Another participant recalled coming into the team and being told, “We’ll get you under XX kilograms,” a weight he had not been since he was 19 years old. “I actually felt so much worse about it,” he said. “You literally do no carbs to go down to that target. I didn’t feel good about it. I didn’t feel strong. I didn’t feel like I had energy to train.”

Another participant described body-fat measurements as being the “be-all and end-all for how professional or how ready you are for the game. In a high-stress and high-performance environment, something small like body composition being a little bit too high, for some managers, it can change their mind on a player and change their opinion on how the players live their lives.”

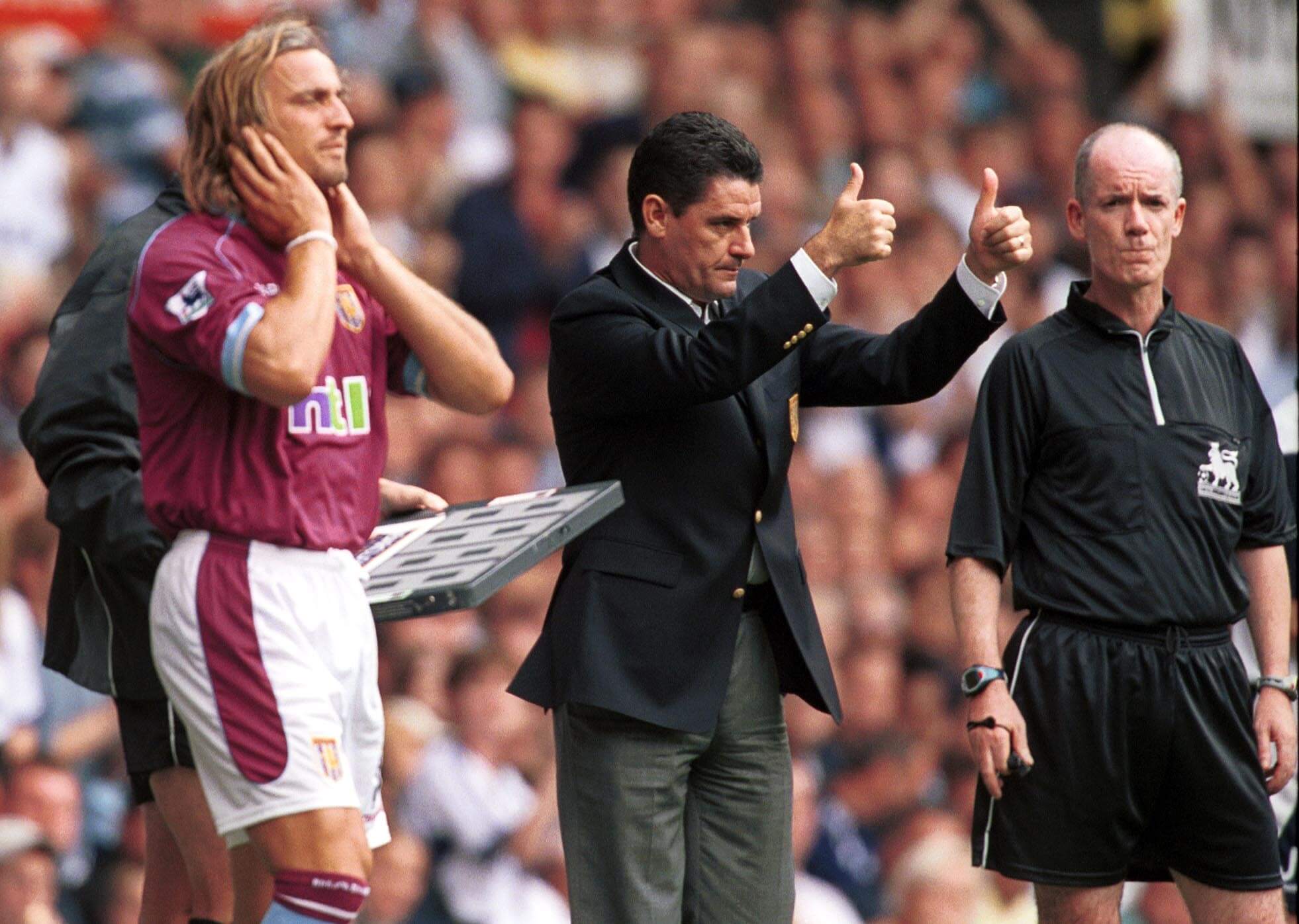

Aston Villa manager John Gregory publicly called David Ginola overweight (Gary M Prior/ALLSPORT/Getty Images)

Morton says the research clearly suggested the influence of the head coach was critical in shaping nutrition culture. “What that can often mean is that some players may align to the coaches’ beliefs, usually with the view that that might influence their chance of getting selected.

“That could mean that players who know that they’re getting tested for body composition within days or a week may engage in dietary practices to make themselves look good on that assessment, which may not align with optimal fuelling and recovery for training and competition.”

Morton’s study uses a term coined by French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu to describe attitudes towards body composition in professional football, labelling the measurement of body fat as a “doxic practice”, meaning it’s based upon a form of social knowledge that is “deeply ingrained in individuals and serves to maintain and reproduce existing social hierarchies and structures”.

The study concludes that there is a doxic belief within professional football about the ideal body composition for players and those who do not “meet expected body composition standards may be seen as unprofessional or lazy, whereas players who fit the perceived ideal body type may be favoured over those who do not”.

What then should change, if anything? “Body composition testing within elite football can still be relevant,” says Morton. “But it has to be done for the right reasons. And it has to be done on the basis of a firm club philosophy where players and stakeholders including coaches and support staff are aligned and educated on the benefits and the reasons why you would want to assess body composition in the first instance, which is much more important than assessment of body fat alone.”

Advertisement

Those “right reasons” could vary, says Morton. In adolescent football, body composition can be used to assess and track growth. “That can then inform when you might want to do certain types of training,” explains Morton. It could also, he says, provide valuable context when a young player is deemed to be underperforming: “If you see that a player is going through growth and maturation that might explain why they’re having a bit of a dip in performance on the pitch.”

At senior level, body composition testing can be used to inform training programme design, and takes on renewed importance during times of injury and rehabilitation when muscle mass is easily lost; again, the focus is more on fat-free mass than on levels of body fat.

“Like any behaviour or practice, it’s often the connotations that create the problem,” says Costello. “We weigh players regularly, but without attaching pressure or judgement. It’s more of a check-in: ‘You’re a kilo lighter than usual, are you dehydrated? Have you missed a meal?’ It becomes a useful touchpoint to guide fuelling and hydration strategies, rather than something to fear. It’s also valuable for tracking how players are responding over time. For example, whether they’re gaining lean mass in line with the demands of training and competition.”

Performance nutritionist A agrees: “It all depends on language, purpose and shared goals and understanding what you’re doing and why, with the players brought into the discussion. When the players engage with it, knowing it’s positive and supportive, that system is beautiful. Nobody is getting told off about their weight being heavy; if anything it’s about that positive culture of getting energy in.”

“We need to treat athletes more ethically,” concludes Costello, “by involving them in decisions about their own bodies and how we manage them. Body composition can be a valuable tool, but it should never become the target. When we shift the focus from numbers to people, when we prioritise performance, wellbeing, and individual context, that’s when meaningful progress happens.”

(Top photo: A skinfold test; by Lucas Dawson via Getty Images)