Forty years ago this weekend, 56 supporters died and over 200 were injured in the Bradford fire as a discarded cigarette or match sparked what became, at the time, the worst stadium disaster in English football.

In the first of a two-part feature, The Athletic speaks to those at Bradford City’s Valley Parade on an afternoon when triumph turned to tragedy.

For Stuart McCall, it’s the ashen-faced police officer quietly revealing an hour or so after Bradford City’s antiquated wooden main stand had been engulfed in flames, “All those who could get out, got out”.

Former police chief inspector Terry Slocombe, meanwhile, recalls vividly how the intense heat meant those pulling fans to safety had to keep retreating to the centre of the pitch to take precious breaths, just as sports reporter David Markham can “still hear the crackling of the timber burning” when he closes his eyes.

Advertisement

Then there’s former England international Trevor Cherry, who never forgot the haunting image of exhausted firemen trying to cope with the horror of what they’d witnessed by taking huge gulps from the gallon-size bottle of whisky he’d accepted earlier in the day as the Third Division Manager of the Year.

Everyone at Bradford City’s Valley Parade stadium on May 11, 1985, has their own story about a day when triumph turned to tragedy and 56 supporters lost their lives.

“The stage was set for a wonderful day with the sun out and the championship trophy being presented,” says supporter Matthew Wildman, the last survivor to be rescued from the burning stand. “But then, in just a few minutes, everything changed.”

In many ways, Bradford remains, to the wider world, the forgotten football disaster. Certainly, it never brought the necessary widespread overhaul in stadia and safety laws that followed 97 lives being tragically lost as a result of Hillsborough four years later.

But the horrors of an afternoon that saw more than 250 seriously injured left an indelible mark that can still be felt today in the Yorkshire city.

“Everyone either knew someone directly who had died in the fire or they knew of someone,” says John Helm, who was commentating on the game against Lincoln City for Yorkshire Television.

Bradford had endured a tough time in the years leading up to the fire. First, there’d been the decline of a textiles industry that had once seen the city dubbed “the wool capital of the world”. And then came the trauma of the Yorkshire Ripper, as Peter Sutcliffe, who lived in the Heaton ward of the city, murdered 13 women between 1975 and 1980 — three of them in Bradford.

Football had offered little respite to the downbeat mood, with Bradford Park Avenue, once a First Division club, having folded in 1974 and City almost following suit nine years later. Had fans not rallied around a ‘Save Our City’ fundraising campaign to pave the way for local businessmen Stafford Heginbotham and Jack Tordoff to buy the club, professional football would have been lost to the city.

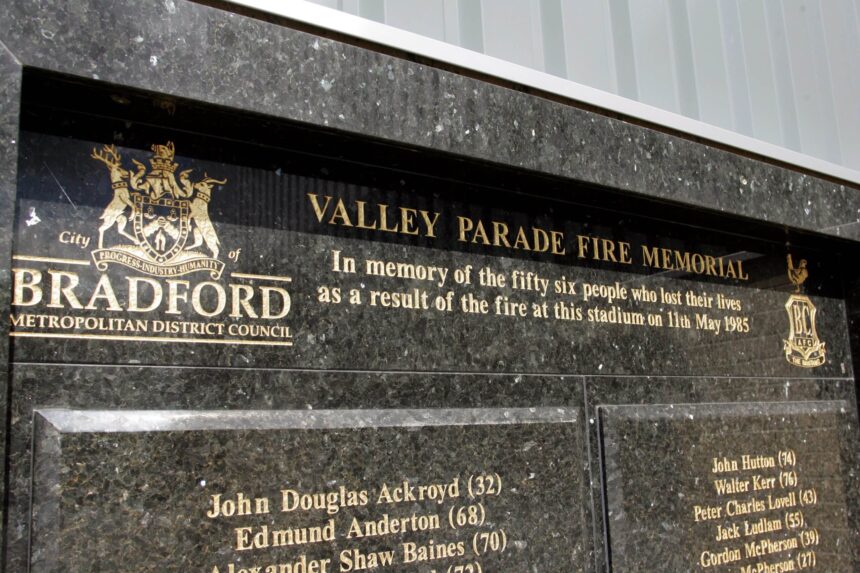

A memorial to those killed in the fire sits outside Valley Parade (Dave Howarth/Getty Images)

No wonder, then, Bradford was determined to party as the Third Division title, clinched five days earlier, was presented to Cherry’s exciting young team shortly before kick-off amid a carnival atmosphere.

“I’ve never found out why the presentation took place before the game rather than afterwards,” says Peter Jackson, Bradford’s captain, who turned 24 just a little over a month before the fire. “But it was such a proud moment for a local lad who’d gone to school just two miles from that stadium.”

Advertisement

Not even a dreary first half against a Lincoln side already safe from relegation could dampen the mood among the sold-out 11,076 crowd. Until, at 3.40pm, came the first sign of trouble, as smoke started to waft into the air from Block G of the main stand.

Initially, there was very little alarm as the game continued and one of three police officers sent to the scene radioed for a fire extinguisher. Another asked City assistant manager Terry Yorath in the home dugout if he knew where the nearest tap was located.

“There was a throw-in being taken when I spotted this orange glow,” says Helm, whose commentary was soon being broadcast to the nation as ITV’s Saturday afternoon programme World of Sport cut to live footage from Valley Parade.

“It was just a tiny bit of flame at this stage. I said on commentary, ‘There appears to be a small fire in the stand’. I had no idea how things would escalate from there. No one did.”

The cruellest irony of the Bradford fire is that it was so close to being avoided. Just one last match and the 77-year-old main stand would have been replaced.

Two days after the final game of the season against Lincoln, work was due to start on dismantling the old structure as Valley Parade was brought into line with modern safety standards.

Promotion to the Second Division meant City’s home would have to comply with the Safety of Sports Grounds Act (1975) that had been brought in following the Ibrox disaster four years earlier, when 66 fans had lost their lives in a crush.

Valley Parade in 1978 – the main stand is to the right (Peter Robinson/Getty Images)

Only clubs in the top two tiers of English football were covered by the Act (known as the ‘Green Guide’), hence Bradford had previously been exempt. Now, though, big changes were needed, with the City board having started to cost a potential rebuild during the promotion run-in.

Eventually, a £400,000 scheme was agreed that would see a new roof erected, all wooden benches replaced, and the entire area concreted. Funding had been secured via a series of grants and City were so keen to get on with things that fans arriving for the promotion party on May 11 could see the steel girders had already been delivered, ready for work to start.

Advertisement

There was no doubt that an upgrade was long overdue. Valley Parade’s main stand wasn’t without its quaint charms, but even in an era characterised by scandalous neglect and complacency, the flaws were considerable. This included a design that effectively split the stand into three distinct areas, starting with those wooden benches at the back bolted onto timber flooring that halfway down suddenly became a block of plastic seats with a concrete floor.

Right at the front was a small paddock terrace. Mercifully — and unlike the two terraces behind each goal at Valley Parade in an era when hooliganism was rife in English football — there was no security fence to keep fans penned in.

Being built on a hillside that sloped down from the nearby Manningham Lane brought another quirk, in that there was a void between the earth and the wooden floor ranging from nine to 30 inches.

An indication of the stand’s age came via the sizeable gaps that had opened up in the floorboards, most likely due to the shrinkage of old timbers over time. This led to all manner of discarded rubbish accumulating in this void, including — fire investigators later discovered amid the charred debris — a 1968 copy of the local newspaper and a pre-decimalisation peanut wrapper.

The subsequent inquiry into the disaster led by Mr Justice Popplewell established that the fire had been started by either a discarded cigarette or match that had fallen between one of these gaps in Block G and ignited the litter below.

“Our job as apprentices was to sweep the stand after a match,” recalls Jackson, who came through the youth setup to captain his hometown club. “Rather than put it in a rubbish bag at the back, we’d sweep it down these big holes. Just as all the apprentices had done before us. No one thought it could be a fire hazard.”

Bradford were far from the only club to have a wooden stand in 1985. Blackpool, Grimsby Town, Exeter City, Doncaster Rovers and Crewe Alexandra all had similar in the Football League.

Advertisement

But Valley Parade’s topography meant the main stand had another unusual feature in that everyone entered at street level on South Parade through turnstiles that led into a narrow corridor at the very back of the stand.

As that initial flicker of a flame started to take hold in Block G — and two and then three and then four rows of wooden benches caught fire — this created a major problem in that human instinct is to leave via the point of arrival. “People also retreat to higher ground at times of danger,” says Slocombe.

At Bradford, this meant heading towards exit gates at the back of the stand that were padlocked shut, and turnstiles that could only be operated by anyone entering from outside.

Had City fallen under the remit of the Green Guide, every exit would have been staffed by a trained steward with a key. Instead, no one was on hand to help as the fans converged on those locked exits. Of the 56 who died that day, 19 bodies were found near one turnstile and 22 next to another. Another three were found in the toilet.

“It was orderly at first,” says Slocombe of the evacuation. “Glynn Leesing, one of the police officers, was trying to move people away from G Block when the flames started. But then, at 3.42pm, the fire really took off. All hell let loose.”

Bradford Chairman Stafford Heginbotham after the fire (PA Images/Getty Images)

As the Bradford City writer for the Telegraph & Argus newspaper, Markham was in his usual press box seat when the fire started. In common with many, he’d not been unduly alarmed at first, but all that changed as the flames suddenly reached upwards in search of oxygen.

Here, they met a pitched wooden roof covered in tarpaulin and sealed with asphalt. The consequences of such a flammable combination were devastating.

“Suddenly, the fire was coming towards us along the roof,” says Markham, a member of the fundraising committee who had helped save the club two years earlier. “If I close my eyes now, I can still hear the crackling of the timber burning.”

The press box being located in the front half of the seated area made the pitch the obvious escape route for Markham and his fellow journalists, even if this did involve scaling two sizeable walls along the way. Others, though, were not so fortunate.

At the height of the fire, temperatures inside Bradford’s main stand peaked at around 900 degrees centigrade — the equivalent of a blast furnace. The subsequent government inquiry also heard how the flames “spread faster than a man could run”, which helps explain how just four-and-a-half minutes elapsed between the first sighting of smoke and the entire stand being engulfed.

Advertisement

Such was the ferocity and speed that the first fire engine arrived from Nelson Street station in the city centre within four minutes, but even that was too late.

What had been an orderly exit onto the pitch suddenly turned into a frantic leap for safety as hundreds clambered over the front wall, and thick black smoke enveloped the back of the stand.

Seventeen-year-old supporter Wildman’s season ticket was on the very back row in Block F. He suffered from rheumatoid arthritis and used crutches at the time due to an inflammation in his joints. Those crutches were stowed in the corridor behind.

“Everyone was so tightly packed in,” recalls Wildman, who had attended the game with three friends. “I had my crutches at this stage, but as I’m small, I was popped down to the floor like a pea. Once down there, I was getting stood on, kicked around.

“Luckily, though, I could breathe because I was under the smoke. Those above me had no oxygen. They were starting to choke badly and some dropped on top of me. I have no idea if those people survived or not.

“At this stage, a guy came running past who was desperately looking for his son. He drags me to my feet, sees the crutches and says, ‘They’re no good now’. He then takes me down the stand and lifts me down to the second block of seating.

“He then had to go and look for his son, but I managed to get myself to the front of the lower stand, only to then find there’s an eight-foot drop to the paddock.“

Wildman remained remarkably calm despite his predicament. Elsewhere, though, panic had set in as tar and bitumen dropped from the burning roof onto those below trying to flee.

A further quirk of the stand’s design only added to the chaos, as fans who had fought their way down the stand were suddenly faced with a five-foot wall due to the front few steps of the paddock terrace being below pitch level. To the elderly and those already exhausted by their efforts to get this far, this simply became an insurmountable barrier.

The remains of the main stand at Valley Parade (PA Images/Getty Images)

John Hawley, the former Arsenal striker who, along with Bobby Campbell, had brought some much-needed experience to a young City team that season, was among the saviours. Despite wearing only his playing kit and boots, he headed towards the blaze and started pulling fans to safety over the wall.

Team-mate Dave Evans did the same, while Jackson also helped drag a young fan to safety. “He was only six or seven,” recalls the former captain. “It was all done in an instant and I’d no idea who he was. But, 26 years later, when I became Bradford City manager, a fella came up to me and said, ‘You won’t remember me, Peter, but you pulled me to safety on the day of the fire’.”

Advertisement

Bradford’s blackest day brought incredible acts of bravery. Four police officers were later awarded the Queen’s Gallantry Medal for their actions, alongside spectators Richard Gough and David Hustler.

Slocombe, who was an inspector at the time of the fire, was among the quartet of officers honoured, along with chief inspector Charles Mawson and constables David Britton and John Ingham.

“It was mayhem,” says Slocombe. “PC David Britton’s hair had caught fire. My jacket was burning. I didn’t realise at first. Someone had to point it out and I threw it off. I then borrowed another officer’s overcoat and went back in.

“It was a fresh day, bit of a breeze, so loads (of fans) had these plastic jackets on. They were melting in the heat as we pulled them out. At one stage, I thought I’d lost a lady. I got her partway out but was forced back to the middle of the pitch to get some air.

“But, by the time I went back, she’d gone. I only found out a couple of days later from another officer that he’d got her out straight after I’d had to go for air. I was so happy to hear that.”

Slocombe’s heroism was far from over. Having spotted three fans trapped in a toilet block, he joined Mawson, who was in overall charge of policing that day, in dashing to their rescue.

“Someone, and I think it was the groundsman, was pouring water over these people,” he adds. “As this is happening, there’s bits dropping from the roof, but we got them out.”

Slocombe takes a moment before adding: “Eventually, it got to a stage where we couldn’t go in any more. I had a personal friend who came up to me and said, ‘My son is still in there’. I had to get really strong with him and say, ‘Mick, you can’t go in’. He was determined to, but we were able to stop him. He would have died.”

Amid this ferocious heat, teenage fan Wildman was still trying to reach safety. But, without his crutches and a substantial drop to the paddock below still to negotiate as well as that imposing perimeter wall, he was in trouble.

“There was a wall to the side of me that was painted,” he says. “By now, the roof is on fire and is basically acting like a grill, toasting everything below, including me and this wall.

Advertisement

“I look down and the paint on the wall is bubbling up. I then look at my hands and they’re bubbling, too. I can’t remember what I shouted — probably something like ‘God, help me’ — but it really was now or never to get over this wall.

“I threw myself over, head first towards concrete steps. There was nothing else I could do without my crutches.”

Fans seek the safety of the pitch as the fire takes hold (Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Enter Hustler, one of those fans later commended for bravery, an assistant supermarket manager who, by this stage, had already rescued one fellow supporter from the burning stand.

“David hears me scream,” adds Wildman. “He told me time and time again after that day, ‘I would have remembered that scream forever if I didn’t try to do something to help’. An incredible man.

“He went back in, knowing full well neither of us were going to get out. But somehow he got me over that wall and out. I was the last person to get out of that fire to survive.”

Hustler’s guardian angel role was far from over. When being carried from the pitch at head height on an advertising board commandeered as a makeshift stretcher, Wildman started to slide off.

Unable to cushion his impending fall due to badly burnt hands, the teenager feared the worst, only to be caught by another fan. He never knew who had saved him that second time until enjoying a drink years later with Hustler, who died in 2016.

“I told David I’d love to know who caught me when I came off the stretcher,” adds Wildman. “He goes, ‘What you on about? It was me!’. Turns out he’d followed me all the way down because he wanted to know the person he’d saved was going to get to where he needed to be.”

The Belle Vue Hotel on Manningham Lane had seen better days by 1985, but, on the day of the fire, this by now rather run-down pub became an impromptu gathering point for the players, coaching staff and their families.

“We were told to head to the pub at the top of Valley Parade,” recalls City captain Jackson. “The TV was on and showing live footage. They were saying there’d been no deaths at this stage, but it still gave you a chill to watch, knowing we’d just escaped from there a couple of minutes earlier.”

Advertisement

For Jackson, that escape had included rescuing wife Alison and their 18-month-old daughter Charlotte from the players’ lounge. With the room fast filling with smoke, the couple opted to make a 10-foot jump to ground level rather than attempt to reach the exit.

“The thing I remember most after getting outside to the street is the eerie silence,” recalls City’s then captain. “No screaming, no panic. Just this silence.”

Eighty fire officers, 12 pumping appliances and six special appliances were eventually needed to bring the fire under control. At this stage, though, those gathered just 200 yards from Valley Parade in the Belle Vue had no idea there had been any casualties.

As a result, McCall wasn’t unduly worried that his dad Andy hadn’t shown up at the Belle Vue along with the other family and friends. As a former professional footballer who had been a team-mate of John Charles at Leeds United in the 1950s, McCall senior was a fit and active 60-year-old.

Nevertheless, McCall still wanted to make sure all was OK, so he headed back to Valley Parade an hour or so after the fire to see if he could collect his car and head home to Leeds.

“I touched the car,” says McCall. “It was red hot and then this policeman came over. His face was the palest I’ve ever seen, so I asked if everything was all right. I only realised people had died when he said, ‘All those who could get out, got out’. My whole body froze.”

Cue a frantic search of the local hospitals that only ended several hours later at Pinderfields in Wakefield. McCall’s father had survived but suffered 30 per cent burns. In time, his body would recover, but the mental scars proved harder to heal.

McCall played 443 matches for Bradford across two spells (Mark Leech/Getty Images)

“I played another three seasons at Bradford, but my dad couldn’t face going back,” says McCall. “In fact, he only saw me play once at Everton and twice for Rangers.

“It was only when I came back to Bradford in 1998 that he felt able to watch football again. I took him around Valley Parade on a non-matchday, showed him the new stand, and after that he was fine.”

Advertisement

As McCall was frantically searching the local hospitals for his father on the night of the fire, hundreds of other worried relatives were doing the same.

“I’d been last out of the stand, so I was the last to be picked up by an ambulance,” recalls Wildman. “By then, all the Bradford hospitals were full, so I ended up (eight miles away) in Batley General.

“I was told later that Pinderfields (in Wakefield, where there was a specialist burns unit) would not accept me because I was too badly burnt. They wanted to concentrate on the ones who were going to survive and I wasn’t going to survive.

“As this is happening, my parents have no idea where I am. A neighbour had gone across to alert them (about the fire). She’s hysterical and saying things like, ‘Matthew won’t be able to get out of there, you’ve lost him’.

“So, when they finally got the call to say I was in hospital with 50 per cent burns, that was better than they’d been expecting. In a funny way, it was almost a relief.”

Cherry, as City manager, remained at Valley Parade longer than most on the evening of May 11. He was still there as the emergency services began the task of combing the burnt-out stand for victims and clues as to their identity.

He saw fire officer after fire officer taking a brief break from those duties to gulp down a huge mouthful from the gallon bottle of whisky he’d been presented by sponsors Bell’s before kick-off as Third Division Manager of the Year. It was their way of coping and the image never left Cherry, who passed away in 2020.

“So many poignant stories from that day,” adds Markham, who still attends every Bradford home game in the press box. “These were the days before mobile phones, so everyone had to wait anxiously for news of loved ones.

“There was one gentleman who had been due to celebrate at a family party that night. His family only realised he’d died when he failed to turn up. Then there was a couple I knew who weren’t together but were companions.

Advertisement

“They always parked their car in Cornwall Road. The car was still there at 7.30pm. I feared the worst when told that and, sure enough, they had both died.”

Sunday will see Bradford’s Centenary Square fall silent at 11am for the annual service of remembrance that has always felt to be a deliberately low-key and introverted affair. A public event to convey a city’s grief that still feels private.

Even the bells of City Hall chiming to the tune of Abide With Me and then You’ll Never Walk Alone invite quiet contemplation to go with the inevitable tears.

Forty years on, the memories of those caught up in the fire remain as vivid as ever. It is why the hackneyed hyperbole so familiar in modern football feels out of place in this corner of West Yorkshire.

Conceding a late goal is not a “disaster” at Valley Parade. Nor is relegation, as painful as it feels at the time, a “tragedy”. In Bradford, they know the true meaning of those words.

“The disaster tends to only get mentioned by the wider public around the big anniversaries,” adds commentator Helm. “In a funny way, though, I think the people of the city are glad it has been forgotten by the wider world. They want to forget. So many were traumatised by what happened that day.”

Part Two will be published on Saturday morning

(Top photo: Allsport UK/Getty Images)