This is the fourth in a series on The Athletic looking back at the winners of each men’s World Cup. Previous articles have looked at Uruguay in 1930, Italy in 1934 and then again in 1938. In 1950, Uruguay were crowned champions again to make it 2-2 between the two countries.

Introduction

Due to the Second World War, 12 years had passed since the previous World Cup in France — during which time the Jules Rimet Trophy had supposedly been stashed underneath the bed of Ottorino Barassi, president of the Italian football federation. As they retained their world title in 1938, his nation had held the game’s most prestigious piece of silverware for 16 years. Uruguay had been the only other winners of the tournament in its inaugural staging. And they would come out on top again here.

Advertisement

Brazil were awarded the hosting rights for World Cup 1950, and therefore they were considered favourites to win it on home soil, just as Uruguay and Italy had done in 1930 and 1934 respectively.

There was still something of an issue in terms of general participation.

Only 31 of the 73 FIFA member nations entered, with Argentina refusing to compete in a tournament they’d wanted to host, West Germany banned from FIFA so soon after the war, previous finalists Austria and Czechoslovakia simply not entering, and Italy present but badly affected by the Superga air disaster in May 1949, in which several of their best players had died. Then France withdrew, after realising the considerable travelling that would be involved between games in a country as huge as Brazil.

Brazil’s downstairs neighbours Uruguay, obviously, didn’t have to come far, and while the European nations struggled with the South American climate, it wasn’t really an issue for the competition’s 1930 winners.

Italian officials handing the trophy over to their Brazilian counterparts ahead of the 1950 World Cup (Intercontinentale/AFP via Getty Images)

You might be surprised to learn…

The structure of this tournament was somewhat bizarre, with Uruguay the major beneficiaries.

The previous World Cup in 1938 had been contested as a straight-knockout tournament, but FIFA — controversially at the time — voted to move to a system featuring four groups of four, with the winners of each one progressing to the next stage.

But withdrawals left the World Cup with only 13 competing teams, not 16. It was too late to conduct another draw, so Uruguay were fortunate to be placed in a two-team group alongside Bolivia (they had qualified without playing a game after Argentina withdrew), who they thrashed 8-0. Contemporary reports suggest the scoreline could have been much greater, had the Uruguayans — three up after 23 minutes — not eased off.

Furthermore, no actual final was scheduled. The top four were to be decided on round-robin results in another (four-team) group, and therefore the organisers simply got lucky that Uruguay and Brazil, the two sides in contention for the trophy going into the final pair of games, met then at the Maracana in Rio de Janeiro.

A draw would have been enough for Brazil to finish top of the final group and so lift the World Cup, which would have been a quite unsatisfactory climax. Uruguay needed a win. That final game was therefore not literally the final, but has come to generally be considered as such.

The manager

While doubt persists about whether Uruguay’s victorious manager in 1930 was truly a manager by today’s definition of the job, there is scepticism about whether their manager in 1950 had complete authority over his side.

While Juan Lopez Fontana had that role officially, the players grew unhappy with his defensive approach. Ahead of that final game against Brazil, the team held a meeting where they were encouraged by captain Obdulio Varela to be braver than Lopez Fontana had requested.

Advertisement

Indeed, at this stage in football’s development, a team’s captain was often considered more influential than the manager. Varela was commended for his pre-match team talks, for ordering his team-mates to behave in certain ways at key moments, and, after the tournament, for disobeying orders not to leave the team hotel, and going out drinking with Brazilians instead.

Lopez Fontana, in fairness, was a highly-respected figure who was still in his job come the 1954 World Cup, then served as an assistant to several subsequent Uruguay managers.

(Fox Photos/Getty Images)

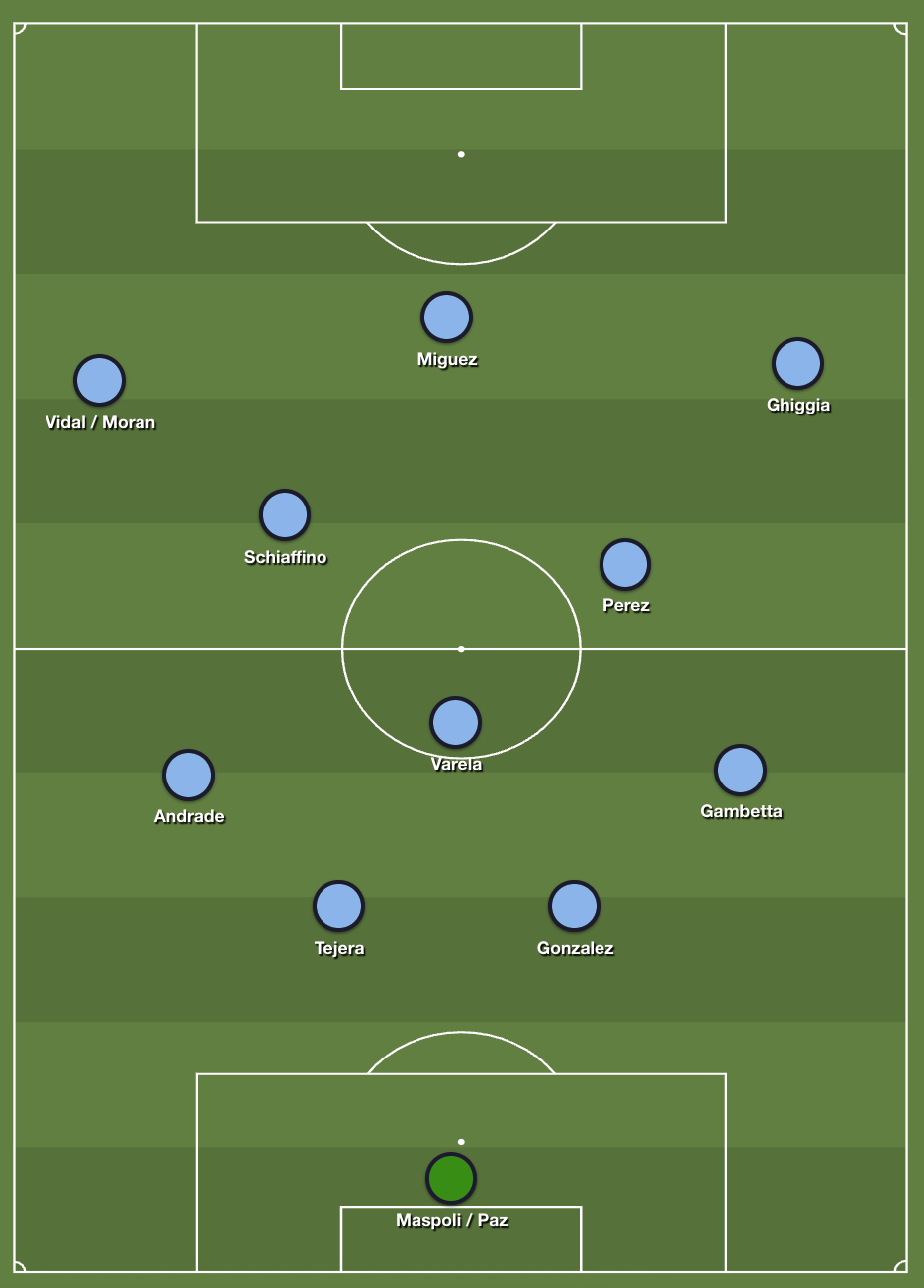

Tactics

While other national teams had shifted towards a system featuring a third defender — the centre-half dropping back — Uruguay’s base formation was more closely related to the system used by previous World Cup-winning sides: two physical defenders, three half-backs, two creative inside-forwards, two quick wingers and a centre-forward.

That said, left-half Victor Andrade (nephew of fellow World Cup winner Jose Andrade from 1930) was written about in almost purely defensive terms, and right-half Schubert Gambetta is also sometimes listed as a defender, too. As other nations beefed up their defence by having the centre-half drop back, Uruguay were gradually moving their right-half and left-half in the same direction. This is why — as Jonathan Wilson notes in his book Inverting The Pyramid — Uruguay are unique in using the No 4 and No 6 as their full-backs in their traditional numbering system.

Like every successful side in these early years of the World Cup, Uruguay 1950 had an outstanding centre-half in Varela, who was physically dominant and also a key attacking weapon. His late, long-range equaliser to secure a 2-2 draw with Spain in their opening match of the final group stage was crucial in allowing them to challenge for the trophy.

Star player

Juan Alberto Schiaffino had all the hallmarks of a legendary South American attacker: slender, elegant, highly creative. He was regularly described as a ‘genius’ and played as the inside-left in Uruguay’s five-man attacking line. He was a clever passer, an elusive dribbler and a prolific goalscorer all in one, notching three goals in this World Cup — including their second-half equaliser in the final.

Advertisement

He was also highly influential four years later at the next World Cup in Switzerland — Uruguay held Hungary, the outstanding side of that tournament, to a 2-2 draw after 90 minutes in the semi-final, but once Schiaffino got injured, they ran out of ideas.

Schiaffino spent the majority of his career with Penarol, who he later managed, in his hometown of Montevideo. Upon his move to Milan following that 1954 tournament, he adopted a deeper role, roughly in the Andrea Pirlo mould, before eventually dropping back even further to become a renowned sweeper for Roma.

Like many South Americans of this period who moved to Serie A, he also switched international allegiance and began to represent Italy rather than his homeland.

He only played 21 times for Uruguay but is probably their greatest ever footballer.

The ‘final’

Brazil versus Uruguay. Bookmakers offered odds of just 1/10 for Brazil to lift the trophy, and there was such confidence across the host country after demolishing Sweden and Spain 7-1 and 6-1 respectively in their first two matches of the second group stage that various newspapers printed front pages on matchday hailing the anticipated triumph.

The modern convention is for opponents to pin these pages up on the dressing-room wall as motivation. Uruguay took things a step further and used them to line the floor of their bathroom. This didn’t help their inside-right Julio Perez, who was so intimidated by the crowd (174,000 officially, possibly around 200,000 unofficially, and probably the largest in football history) he wet himself as the anthems were being played.

Foreshadowing Brazil’s collapse, shortly before the game, their flag was raised… upside-down.

Once the match kicked off it was all Brazil, with Uruguay defending their box manfully, and hoofing the ball clear rather than putting together any notable counter-attacks. But both sides hit the post before half-time — Oscar Miguez for Uruguay, Jair for Brazil.

Advertisement

Brazil went ahead barely a minute into the second half, with Friaca firing a low shot into the far corner from the right flank. This prompted Uruguay captain Varela to pick an argument with George Reader, the English referee, over a non-existent offside, which included him requesting an interpreter at one stage. Varela knew there had been no offside, he simply wanted to halt Brazil’s momentum.

Uruguay hit back, and their key player was now Alcides Ghiggia, who constantly motored past Brazil’s hapless left-half Bigode. Midway through the half, he beat Bigode, looked up and found Schiaffino making a run to the near post for a cutback. The ball bobbled slightly before Schiaffino hit it, but this meant he produced a shot with both power and curl inside the near post, although he later admitted he hadn’t intended to strike it quite in that manner. No matter, it was 1-1.

That result would still see Brazil crowned champions. But the momentum was now with Uruguay.

Schiaffino makes it 1-1 in the ‘final’ versus Brazil (AFP via Getty Images)

The defining moment

Ghiggia was the star player in the final, and having galloped down the Uruguay right to create the opener, he threatened to do the same thing 11 minutes from the end of the 90.

Schiaffino was waiting to score a carbon-copy goal, and that’s what Brazil goalkeeper Moacir Barbosa expected. But Ghiggia could also fire home at the near post, as he’d done a week earlier in that draw with Spain. That’s what he did here, rifling home the winner.

Barbosa was regarded as Brazil’s best-ever at his position but got harshly blamed for what was, by the goalkeeping standards of the time, a relatively minor error, including having to flee his home after receiving death threats, He and Brazil’s other Black players received disgraceful abuse after this loss, being labelled unpatriotic.

Following this World Cup, Barbosa worked in an administrative role at the Maracana, scene of his disastrous moment. Several years after the event, he was presented with the goalposts he’d allowed the ball to squeeze between. He sawed them up, took them home and burned them, as a form of exorcism.

Advertisement

But that wasn’t the end of his pain.

Brazil’s treatment of him was despicable, considering he was possibly the country’s best goalkeeper of the 20th century. More than 40 years after this match, in a country big on superstition, he was both removed as a commentator from the broadcast of a Brazil game and shunned when visiting the national team’s training camp, because of fears he would bring them bad luck. He died in 2000, aged 79, after years of loneliness.

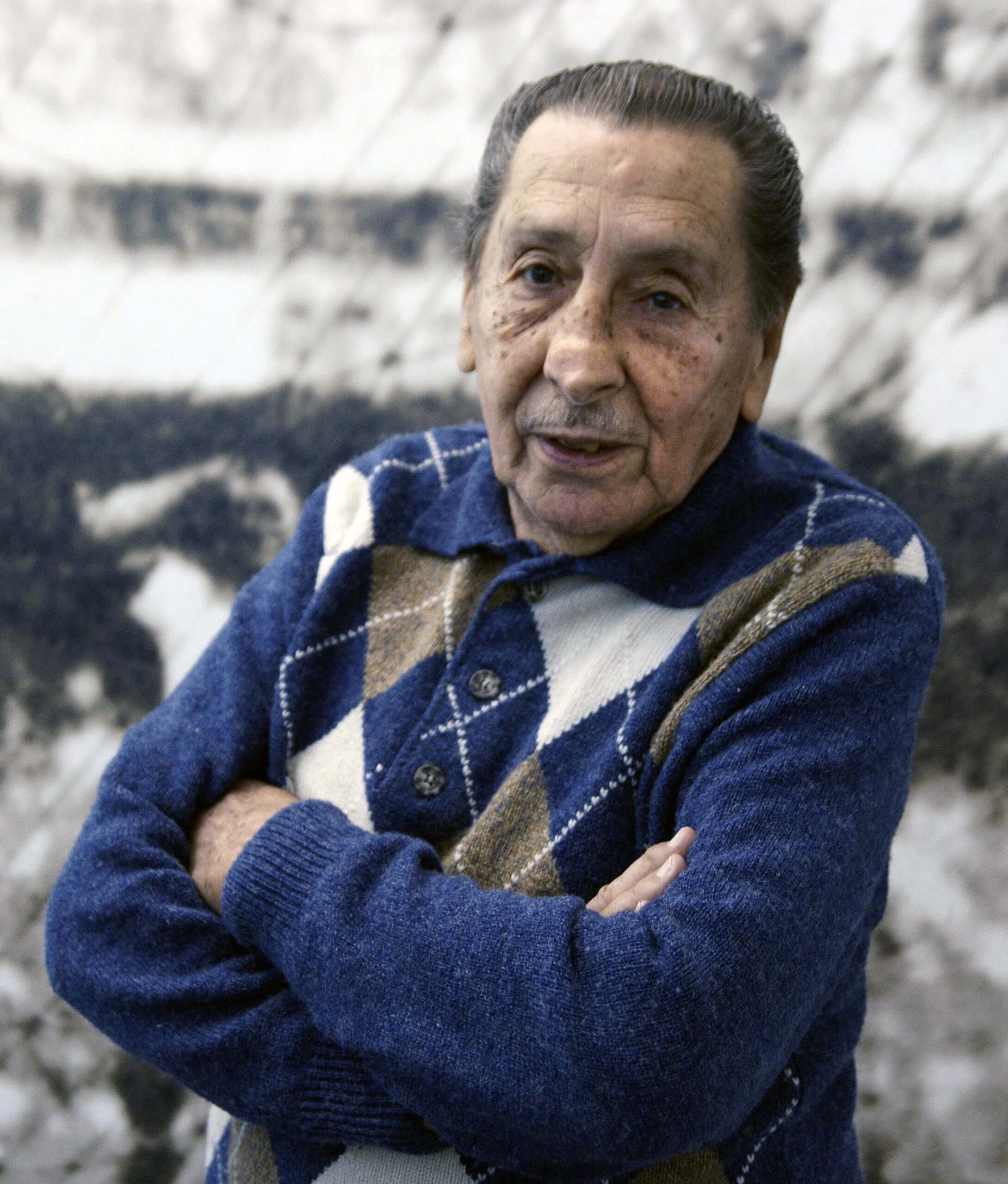

Amid all the anger they directed at their own team, Brazilians reacted sportingly to Uruguay’s victory. They applauded the winners at their trophy presentation. Ghiggia was always respected in Brazil, returning to the Maracana in 2009 to be inducted into the stadium’s walk of fame. He died in 2015 — 65 years to the day after his famous World Cup-clinching goal.

All sorts of quotes have been attributed to Ghiggia, some of which seem a bit too Hollywood to be taken seriously. But his summary of the key moment is a nice analysis of the risk-and-reward of shooting for the near post, rather than crossing. “Barbosa did the logical thing,” he reportedly said. “And I did the illogical thing.”

Alcides Ghiggia, pictured in 2010 (Panta Astiazaran/AFP via Getty Images)

Were they definitely the best team?

Surely not. Uruguay only played four games — two fewer than Brazil. Not only did they have the fortune to compete in a two-team opening group against minnows Bolivia, they didn’t perform particularly well in the second one, having to come from behind in that 2-2 with Spain and only squeezing past Sweden 3-2 thanks to an 85th-minute goal.

In contrast, Brazil had beaten the same opponents by a combined score of 13-2, having previously finished top of their (four-team) first-round group via clean-sheet wins over Mexico (4-0) and Yugoslavia (2-0) and a 2-2 of their own with Switzerland.

In his history of the World Cup, Ian Morrison says their 1950 side played “some of the finest football ever played at international level”, while Brian Glanville described the Brazilians as playing “football of the future — tactically unexceptional but technically superb”. Their three central attackers, in particular — Jair, Zizinho and Ademir — received rave reviews for their combination play.

Advertisement

But ultimately Brazil, as a nation, exuded overconfidence going into the final game, and the players themselves suffered from nerves — not for the last time in a World Cup.

Often, knockout competition can produce the ‘wrong’ winners, but this World Cup was decided by a league table, which tends to favour the better sides on paper, and Brazil still couldn’t get over the line.

They would have to keep on waiting. By the time of the next World Cup, they had ditched their white kit, now associated with this 1950 failure, in favour of the yellow, green and blue strip known worldwide today.

Four editions in, the World Cup had still been won by only two nations, with Italy and Uruguay crowned champions of the two tournaments played on their home continents of Europe and South America respectively.

But things were about to change in 1954.

(Top photos: Getty Images; design: Eamonn Dalton)