The week ahead marks 20 years since the Glazer family acquired a controlling stake in Manchester United, going on to complete one of the most controversial takeovers in football history.

To mark such a significant moment, The Athletic will be running a series of articles and podcasts about the takeover and the 20 years since to go deep into what happened, the consequences for Manchester United and what happens next.

It begins today with the retelling of the original takeover and the family who bought United. A version of this article was published in 2020, it has been substantially updated to reflect the 20th anniversary.

In the seconds after Wayne Rooney swept Manchester United into a Champions League lead over Debrecen on a balmy August evening in 2005, a question asked in the directors’ box caused unique confusion.

“It was, ‘What happens to the baaall?’,” says a former United executive, mimicking the drawl of an American accent.

Advertisement

Toxic takeover completed a few months before, the Glazer brothers — Joel, Avie and Bryan — were attending their first match at Old Trafford as owners of Manchester United and a new way of thinking was evident. Bryan was the one to vocalise the mindset that everything, especially a Rooney goal, could now be ripe for marketing.

“He thought, as in baseball or American football, ‘They must have loads of balls’, and when they hit a home run or score a touchdown, it becomes an item,” continues the executive. “That concept just didn’t apply in England. It was chief executive David Gill who said, ‘They put it back and we start again’. The story is the incomprehension on everyone’s face. And we were genuinely at a loss. It wasn’t people laughing at them. It was people not understanding.

“It shows two things: one, that you need cultural grounding to run a football club. And two, that these guys were considering every possibility.”

It was a disposition for considering every possibility that got the Glazers the club in the first place. The leveraged buyout, the eye-watering interest rates, the hundreds of millions of pounds of debt may have been unpalatable to many, including numerous financiers, but the Glazer family, helmed by father Malcolm, was lasered on a capitalist course that culminated 20 years ago this week.

On May 12, 2005, the Glazers’ holding company Red Football announced it had reached an agreement with Manchester United shareholders JP McManus and John Magnier to purchase Cubic Expression’s 28.7 per cent stake in the club. That was the ball game. The Irish racehorse owners, in dispute with Sir Alex Ferguson over the stud rights to Rock of Gibraltar, had made the decisive move.

To coincide with the date, The Athletic has retraced the events that led up to an unprecedented takeover and delved into what life became like at United.

In the immediate aftermath, on May 26, 2005, Manchester United’s board wrote to the few remaining shareholders to outline their intention to sell up and they advised the recipients to do the same. Chairman Sir Roy Gardner and non-executive directors Ian Much and Jim O’Neill also offered their resignations.

Advertisement

Just 11 days earlier, a different resignation had been the subject of conversation when Sir Alex Ferguson picked up the phone to one particular United fan. Andy Walsh was an activist with the Independent Manchester United Supporters Association (IMUSA) and the evening after United’s final-day victory at Southampton, he rang British football’s most garlanded manager with a Hail Mary of a proposition.

“My call to Alex Ferguson was to ask him to consider resigning,” Walsh tells The Athletic. The two men had built up a relationship during conversations over many months; a mark, Walsh says, of Ferguson’s “focus on detail and integrity”.

“He genuinely believed the supporters should be heard in the takeover,” Walsh says, and in November 2004, Ferguson said in a fan forum: “We don’t want the club to be in anyone else’s hands.”

But six months later, the Glazers had strengthened their grip and those working to stop them believed only a dramatic intervention would succeed. “Our last throw of the dice,” Walsh admits. There was a theory, though.

“It was a highly leveraged takeover and major corporate financiers were already shying away based on what was being proposed,” Walsh says. A club free of debt since 1931 would be placed £580million ($776m at current rates) in the red, with risky payment-in-kind notes (PIKs) meaning the interest alone in the first year stood to reach £63million.

“We felt any loss of support from senior management executives — Ferguson and Gill — would have dealt a fatal blow.”

Walsh was among a group of fans working with Shareholders United and the Japanese bank Nomura on a rival bid for the club and, in a way, he was an idealist. “If the deal collapsed, Ferguson would then be carried back into the stadium on the shoulders of supporters,” he says.

But he was also a realist. “Ferguson politely declined, believing he had a responsibility not just to himself and his family, but also all the people he had brought to Old Trafford and were working under him.

Advertisement

“We were asking him to take a huge risk. There was no legal undertaking we could give him. Just a word. We believed the club would then be controlled by fans rather than people draining it for personal profit. That was the point I made to Alex Ferguson in that call. But I fully respect and understand his decision.”

Ferguson with Bryan, Avram and Joel Glazer in July 2005 (John Peters/Manchester United via Getty Images)

Resentment simmered among significant sections of supporters. Some formed their own club, FC United of Manchester, instead of setting foot back in Old Trafford. A wealthy collection of supporters, christened the Red Knights, launched a takeover attempt in 2010 that gained visible backing in the stadium through the green-and-gold campaign. The publicity, gained through a leak from within, meant the consortium lost the element of surprise, which people believe made the Glazers raise the asking price.

O’Neill, the former Manchester United board member, is speaking publicly for the first time about the episode. “In principle, we still thought we might be able to work our way through, but the interplay with the media coverage had an impact,” he says. “There was so much attention. For most of that week, it was the main BBC story, incredible.

“It was very tricky for me because I never said publicly that I was doing it and I was still a full-time employee and partner at Goldman Sachs. And so the madness of it was really hard to control. But it meant the Glazers concluded, ‘Wow, this thing is even way bigger than we thought’.

“Certainly, they never showed any direct desire through their people I was speaking to that they would sell. They floated stories that they’d turned down amounts they perceived to be bigger than what we’d think about offering, which I’m pretty sure they hadn’t, but it was quite clever of them to do that.”

Rancour remained. In 2021, a militant core sparked a criminal investigation by attacking Ed Woodward’s house with fireworks. Those scenes are why some former directors spoke to The Athletic on condition of anonymity, with memories still fresh of the occasion in October 2004 when Maurice Watkins, United’s club secretary, had his car vandalised with red paint after it emerged £2.5million worth of his shares had ended up in Glazer hands. At one point, an effigy of Malcolm Glazer was hung from the Stretford End of Old Trafford.

Similar strength of feeling was witnessed on June 29, 2005, the day Joel, Avie and Bryan visited United’s stadium for the first time. The Athletic has spoken to colleagues who recall the brothers being “shaken up” when several hundred angry United fans blocked the exits, meaning a police van was enlisted to secure their departure.

Advertisement

However, the Glazers will feel their gamble has paid off. By the time the £790million takeover was complete, they had put in roughly £270million of their own money — although some City of London sources are “dubious” it was that much, suspecting even that cash was leveraged against their American businesses. They borrowed the rest and used the club as collateral, turning a personal profit by the summer of 2022 through through dividends, management fees and share sales, and leaving the debt effectively untouched (although it is £180m higher now than the initial borrowing).

Then came the sale to Sir Jim Ratcliffe, which gave them $909.2million collectively, about £679m at today’s rate, to take them over the £1billion mark for cash in their accounts, up to £1.35bn.

After all that, they still own 48.9 per cent of the club and control 67.9 per cent of the voting rights due to the weight of their Class B shares compared to Class A shares. Ratcliffe paid $1.54billion for his 28.9 per cent share, which was then transferred to INEOS, valuing the club at £4.3bn.

Despite fighting tooth and nail to take control of Manchester United, several people familiar with the matter say Malcolm Glazer never set foot inside Old Trafford. The Glazer patriarch died on May 28, 2014 and, in truth, very little came to be known about the man who altered United’s history so drastically. The only crumb of insight given by the family remains Joel’s interview with MUTV from that visit to Old Trafford in June 2005, in which he stressed communication with fans was “extremely important”. He said, “Fans are the lifeblood of the club. People want to know what’s happening. We will be communicating.”

Instead, when United lodged accounts one year later, the accompanying note from Tehsin Nayani, the Glazers’ PR at the time, read: “There will be no press release, there will be no press briefing, there will be no press interviews.”

Nayani would go on to write a book called The Glazer Gatekeeper — Six Years’ Speaking for Manchester United’s Silent Owners, the most extensive record of the family in publication, albeit far from revelatory. Nayani detailed how the brothers deliberately wore red ties for the Debrecen game and also described being introduced to Malcolm before a match involving the Glazers’ NFL team, the Tampa Bay Buccaneers: “Malcolm’s wispy ginger hair was finely groomed and, holding my gaze with his piercing blue eyes, he offered the silkiest, softest handshake I had ever experienced.”

Responsibility for communication was passed to Woodward who, people familiar with the situation say, spoke to Joel every single day, without fail, and sometimes more than once. United’s executive vice-chairman has been known to tell of the occasion the pair ended up in a heap together in the stands of Moscow’s Luzhniki Stadium while celebrating the Champions League final victory against Chelsea.

Avram and Woodward at the 2008 Champions League final (AMA/Corbis via Getty Images)

Joel also has a photograph hanging on his wall from the Manchester derby held on the 50th anniversary of the Munich air disaster in 2008, when sponsors were shorn from the shirts. His offices in Washington, DC, hold a replica of the United dressing room, with all of the first-team shirts hanging up on the benches, and the boardroom is dominated by a huge picture of George Best in the 1968 European Cup final.

Advertisement

Despite the Buccaneers winning the Super Bowl in 2003, Malcolm’s affection for sport was never quite as evident. One account of this aspect of his life comes from Allen St John, a journalist who met the head of the Glazer family over a possible book commission in 2000.

Glazer had owned the Bucs for five years to this point but St John tells The Athletic: “I don’t recall us talking about (American) football at all. He didn’t say, ‘This is why I love the team’. Most owners of sports franchises love to talk about their teams.”

Glazer did provide some indication of his NFL allegiance, however. “He gave me this Buccaneers pin, very ceremoniously,” says St John.

The hour and a half St John spent in the company of Glazer in a New York hotel room was curious for the fact that there were few discernible traces that the man proposing the book was a billionaire. Bryan was also in attendance.

“It was something my agent set up,” St John says. “It was at the Hilton and both of them were sharing a reasonably small room. There were two twin beds. I was sitting in a chair between — we were perched around.

“Malcolm ran the meeting. He had ideas about the stories he wanted to tell, money-making ventures from when he was a kid. There was a long story about watch parts. He was talking about his early life, going back to the Depression, and seemed very proud of it, his work ethic, how hard he had it. It is what we think of now as quaint. But he proved his cleverness, his thrift, his ingenuity.

“I was a little bit surprised. I thought the book would be, ‘Hey, I’m a billionaire, you’re not’, but we never got into the bit about him going from nickels and dimes to billions. I mostly exchanged pleasantries with Bryan. He was sitting there pretty quietly and listening. I got the impression he had heard these stories before.”

Advertisement

Then came a curious episode that, again, St John felt Bryan was used to. “A valet had dropped off a pair of Bryan’s pants from dry cleaning. It caught Malcolm’s attention. He said, ‘Those are Hugo Boss pants, do you know how much they cost? $200. But I like my pants better than his’, and he points to them. ‘I bought these at JC Penny, $19.95, and I remember what it was like not to be able to afford $20’.

“I remember feeling really kind of bad for Bryan. My father might have joked about that at a family gathering but not at a business meeting with a stranger. Bryan was squirming a little bit. We are roughly about the same age — at that point, in our late thirties.”

Ferguson with Bryan Glazer in Beijing (Photo: John Peters/Manchester United via Getty Images)

There was one final thing that left St John perplexed. “Towards the end of the conversation, he asked me if I thought we could do this without my agent,” he says. “I was confused because the fact is my agent was bringing me to the project but also, more importantly, he would actually go and sell the book. If we did this around him, it would have derailed the process. I didn’t get the impression Malcolm had his own agent. It seemed to be mostly about the money. At that point, I was like, ‘I’m not sure’.

“I have collaborated with other people and you have to work hard. You need a level of trust. That he was willing to discuss having the person who set this meeting up out of the venture didn’t make me feel very good about my own security in those circumstances.”

There is no autobiography on the bookshop shelves, so we can only wonder what Glazer might have said about Manchester United and whether he would have included a chapter on the day his sons required a police escort out of Old Trafford.

In the final week of June 2005, Joel, Avie and Bryan embarked on a charm offensive in England, travelling to London for meetings with Richard Scudamore and Brian Barwick, the chief executives of the Premier League and FA respectively, and Richard Caborn, the sports minister.

“It was hush-hush that they were visiting the UK because of the protests,” says one person familiar with what happened. The meetings were only set up a day or two in advance, with David Gill, United’s chief executive, calling the FA and Premier League himself.

Advertisement

Gill would accompany the Glazer brothers every step of the visit, just five months after opposing their takeover. In December, he sold £1.3million worth of shares to Jim O’Neill, a lifelong United fan and board member, to keep them away from the Glazers, and privately offered a donation to Shareholders United that activist Nick Towle said was worth £25,000. Although, when asked, Gill’s recollections were that the sum was not that high.

The previous autumn, Gill had called the Glazers’ proposals “aggressive” and potentially “damaging”, although The Athletic has learned Gill now denies stating “debt is the road to ruin”, the words that are stretched across a famous green and gold banner. At the time, he said he had been taken out of context and when confronted with the quote by a fan at Birmingham University in 2010, responded only that “the model changed”.

Some speculated Gill’s previous stance would see his job in jeopardy but the Glazers, according to people familiar with the matter, “were very keen to keep David on board to provide that continuity, not just for staff but for regulators”. One person describes that as a “shrewd move” because of Gill’s influence in the corridors of power and the following summer, he was elected to the board of the FA. What is more, The Athletic understands Gill staying put increased the chances of Ferguson remaining at the club, too.

Over the next five years, Gill’s pay rose from £1million to £1.95million and upon leaving United in 2013, he was elected to UEFA’s executive committee.

That future was unclear when he introduced the Glazers to England’s football authorities, whose main concerns pertained to the collective selling of TV rights. Scudamore, Barwick, and Caborn all asked whether the Glazers would blaze an individual course but they provided reassurances. “We come from a much more egalitarian distribution system than you guys,” they said. “All the marketing and TV rights are centralised in the NFL, then they get dished out evenly among all the members.”

Caborn tells The Athletic: “They weren’t aggressive. They weren’t in-your-face Americans. I got the impression they were looking for a synergy between what was happening in the U.S. through sport, television, and commercial, and whether that could be applied to Manchester United. The Premier League is big but in terms of basketball or American football turnover, we are nowhere near.”

Supporter groups feel Caborn could have done more as a government minister to protect United from the financial risk of the Glazer takeover, and even Solskjaer signed up to the resistance movement in February 2005 after doing extensive background research. He remains listed as a patron on the Manchester United Supporters Trust website.

Advertisement

Concerns came not only from the debt placed on the club but also from the Glazers’ PIK loans (worth £220million) which allow borrowers to pay interest with additional debt, rather than cash. The three hedge funds — Perry Capital, Och-Ziff Capital Management and Citadel — who lent the money were entitled to demand seats on the board and a share of capital in United if payments had been late.

“One of the big gripes we had was that in an NFL franchise, you couldn’t leverage more than around 15 per cent in a takeover,” says Sean Bones, who was a key member of Shareholders United 20 years ago. The current limit is a flat rate $1.4billion leverage, a figure that has gone up over the years — with the average NFL team valued at $6.49billion, that equates to around 21.5 per cent. The Glazers leveraged close to 66 per cent of United.

Bones worked in a factory half a mile from Old Trafford and on match days, would canvass for support in the alcoves of the stadium, trying to get ordinary fans to buy shares. “I was devastated when the Glazers took over. I thought we were really close to our own takeover,” he says. “We were attending regular meetings in the Old Trafford boardroom on Friday afternoons to discuss how we felt with Gill and others. And I can remember coming back from one particular meeting in London pretty convinced.”

Bones is talking about the Nomura deal and the group’s confidence was buoyed by having Russell Delaney in their ranks. Delaney had a contact into the Coolmore horse-racing group, which owned 28.7 per cent of United shares.

Coolmore, led by John Magnier and JP McManus, had amassed their holding during a friendship with Ferguson, who wished to solidify his power base when United was a plc, but their relationship soured over a dispute for the stud rights to Rock of Gibraltar. “That bloody horse”, as Michael Crick, the respected author and United fan, decries to The Athletic.

Ferguson with Rock of Gibraltar (Tom Hevezi – PA Images/PA Images via Getty Images)

As the legal arguments escalated and spilt into the public, Magnier and McManus applied pressure on Ferguson in January 2004 by issuing 99 questions on United’s transfer dealings, buying more shares and hiring private investigators. Ferguson complained about people going through his son Jason’s bins. Coolmore have always denied any of this was to do with them.

Ben Hatton, who was United’s head of commercial enterprises for 10 years up until 2007, says Ferguson’s job came under threat, too. “This enormous acrimony developed between two parties, which led the Irish investors to want to use their shareholding at the time as leverage to put pressure on Sir Alex,” Hatton tells The Athletic. “It became clear some kind of white knight shareholding was going to be necessary to prevent what we expected to be a full takeover.”

Advertisement

So Magnier and McManus were kingmakers for potential buyers and through his connections, Delaney believed supporters would be allowed the chance to offer a counterbid should the Glazers make a satisfactory offer. But that did not happen and, to Delaney’s surprise, on May 12, 2005, Red Football, the Glazers’ investment arm, announced it had reached an agreement to purchase the shares of Magnier and McManus.

“They took a risk with the whole club’s future that shouldn’t have been allowed by the government,” Bones argues.

Caborn counters: “We couldn’t have put blockers on it. That would have been the regulators of the Premier League and FA. Once they’d passed the fit and proper person’s test, there is little any government can do.

“I’ve been a Sheffield United fan since I was eight. I know what a club means to a city or a town. We were interested, as a government, to make sure the ownership of Manchester United wasn’t falling into bad hands and was going to continue to play a big role in the community. And to be fair, they have basically done that.”

O’Neill, who coined the BRIC economic term and was made a Lord in 2015, says: “As a publicly quoted company, I don’t think there’s much the UK government could have done without having a much broader message for foreign investors. You know, what’s to stop them doing that about Marks & Spencer or British Airways? The way that it could be done, and this bill hasn’t passed through Parliament yet, but under the new regulator, if there’s genuine focus about how much debt can be used to own a sports business, especially football, that would definitely get more scrutiny.”

Caborn, right, with Ferguson and Seb Coe in 2006 (John Peters/Manchester United via Getty Images)

David Davies, a three-time FA chief executive, was an outgoing director when he took a call from the incumbent Barwick on Tuesday, June 28, 2005. He says, “Brian, a true Liverpool supporter, said, ‘Hey, these guys the Glazers are coming to the FA. You must meet them’. I was a well-known Man U person.

“I was aware the takeover was controversial but I was also aware that people like Ferguson were supportive. It was a very affable meeting. I was keen to establish, ‘Did these people care about Manchester United?’. It appeared to me there had been some work done on their history.

Advertisement

“I have been a United season ticket holder since the day I left the FA. I sit in the South Stand and would have to be living on planet Zog to not be aware the ownership remains controversial.

“If Manchester United had stopped buying great players, I would be more critical than I am. It was always going to be difficult to follow Ferguson but some of us are long enough in the tooth to know what it was like following Matt Busby.

“I clearly have views on the fit and proper person’s test. Is it all satisfactory? I wouldn’t pretend there are not still questions to be answered. You can argue about ownership regulations and who should have those powers, for sure.”

The Glazers’ final meeting on their London trip was with Caborn in his offices by Trafalgar Square. He had business that evening at the House of Commons and the brothers asked if he would provide a tour once he was done. “Americans love it because they’ve not got history like we’ve got,” Caborn says.

The Glazers were driven in the ministerial car while Gill walked down Whitehall and queued up at St Stephen’s entrance. The group then dined together in the Churchill Room.

In a series of statements, all parties expressed satisfaction with the meetings. But easing the concerns of the establishment was one thing. Winning over United’s supporters would be quite another.

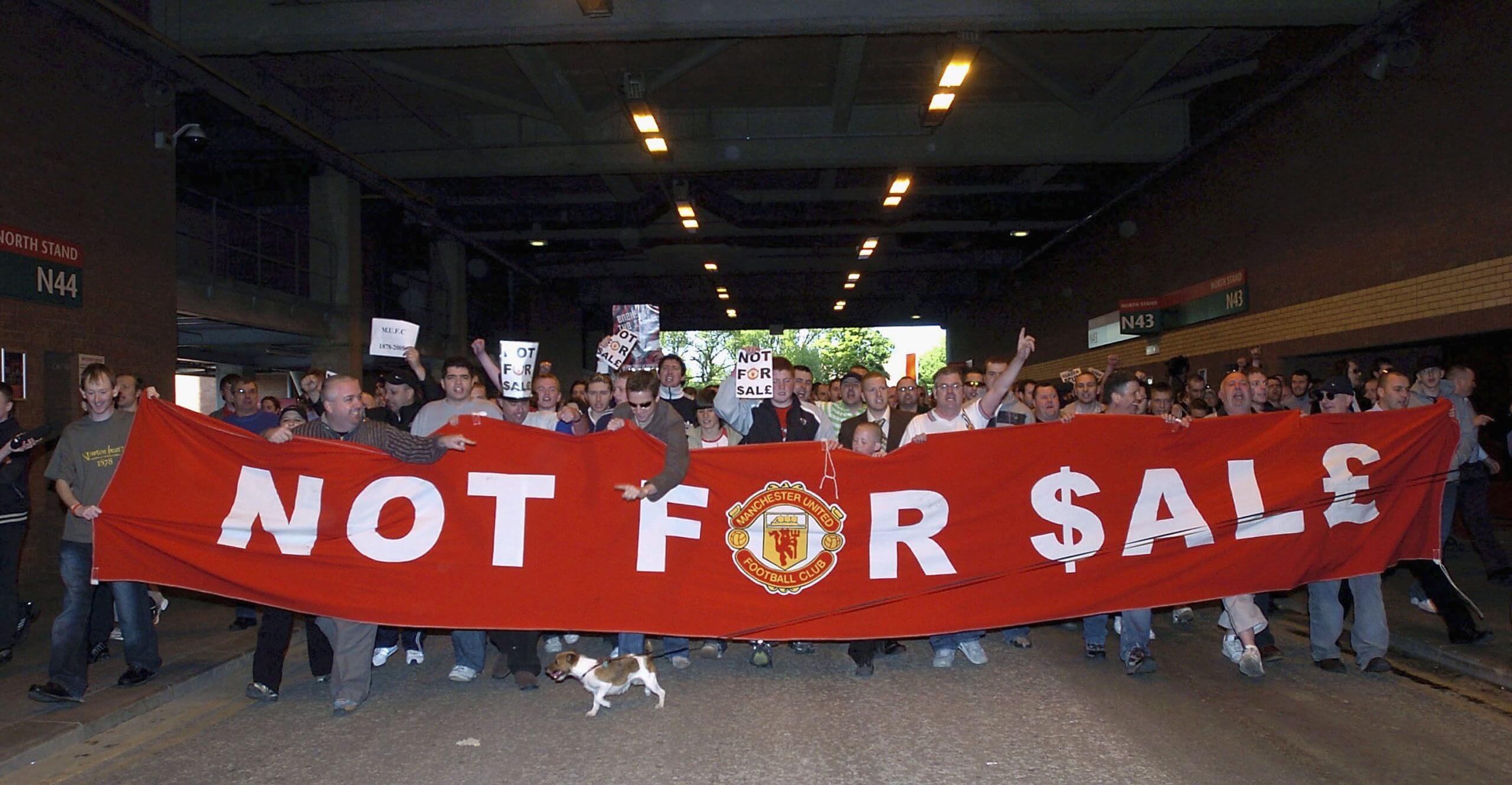

At 6.15pm on Wednesday, June 29, the brothers arrived at Old Trafford in silver people carriers to meet executive staff members. Word got out. Reporters and photographers arrived. So, too, did around 400 United supporters, who gathered throughout the evening on the stadium forecourt to sing anti-Glazer songs. “We’ll be running round Old Trafford with his head,” was at the softer end of the spectrum.

Fans protest against a sale to the Glazers in May 2025 (Matthew Lewis/Getty Images)

United’s security team erected a steel gateway around the directors’ entrance and fans responded by building barricades on the road.

Riot police arrived with dogs and inside the stadium, staff wondered how on earth they were going to get out. “It was quite scary,” says an individual in the Platinum Lounge with the Glazers that night. “We had to wait inside.”

Advertisement

Around 10.25pm, an engine roared and the doors of the players’ entrance at the Stretford End were flung open. Two police vans, with the Glazers inside, sped through. Some fans tried to pelt them with stones. Two people were arrested.

The following day, Sir Bobby Charlton, who had expressed concerns about the takeover, arrived at Old Trafford to meet the Glazers. Afterwards, he told reporters he had apologised to the club’s new owners for the scenes the previous night. “I tried to explain they couldn’t ignore the fans, who are so emotionally involved in the club but sometimes do go a bit too far.”

Charlton’s first impressions of the Glazers were positive. “Like any other football fan, I’ve been waking up in the night wondering what was going on,” he said. “But they allayed a lot of my fears.”

Such sentiments were not enough for some fans, who formed breakaway club FC United instead of sending their money towards the Glazers. Andy Walsh was 43, thinking back on 38 years of memories following United when he sat in his car outside Old Trafford preparing to withdraw his season ticket renewal. “I cried,” he says. “It’s irrational, isn’t it, but those feelings make us human. If you turn it into a purely transactional relationship, you undermine the emotion and damage the sport.

“It caused a lot of hurt fans to walk away. People would ask me what they should do. One fan turned up to my house, distraught, wringing his hands. He’d lost jobs through following United and here he was considering giving it all up. I saw him a few months later at FC having the time of his life.”

Walsh could not square his love for the team with what the club would become. “Yes, the Glazers have squeezed more revenue through the commercial deals but in doing that, they’ve suffocated the soul of the club, in my view,” he says. “They are leeches.”

On the business model page of United’s investor relations website, two pie charts are displayed. One shows how commercial revenue stood at £66million in 2009, accounting for 24 per cent of the overall turnover. Another from 2019 puts that figure at £275million and 44 per cent of the total income. The chart below shows how those figures have evolved.

“There is a bigger argument about the shape of the game,” argues a former director. “United didn’t change the face of football on their own. Barcelona, Real Madrid, Milan, Bayern Munich; all those clubs were chasing sponsorship money.”

Still, nobody did it quite like United, who pioneered the proliferation of sponsorship categories. Listed at one stage on their official website were 25 global partners, eight regional partners, 14 media partners and 14 financial partners — a total of 61 sponsors. It was the realisation of the Glazers’ ambition when buying the club. According to people familiar with the matter, they were incredulous that the Tampa Bay Buccaneers had larger commercial revenue than United, despite NFL regulations limiting team sponsorships to a 75-mile radius. “If you go to Tampa Bay, you can see sponsors plastered all over the place: a DIY chain, a chicken restaurant, a car dealership; they’ve got tonnes,” says a former executive.

Advertisement

The Glazers transposed the model to United on a global scale. “The first new deal the Glazers did was with the Saudi Telecom — £5million with no signage rights; just the branding in Saudi,” says an executive. “That’s when we realised there might be something to their approach.”

Another former director says: “The stock market struggled with a company whose revenue is dependent on success on the pitch. It was undervalued. That’s what allowed somebody who did see the value in a global brand to buy it. Woodward sold it to the Glazers and they took the risk. They leveraged the deal but they did put their money into it. If it had all gone wrong, they would have been wiped out. Their view was, ‘We took the risk, we should get the rewards’.”

Woodward, according to a separate former colleague, was “the architect of their business plan and central to its implementation”. Once the takeover was complete, he left JP Morgan, the bank facilitating the Glazers’ lending, and “wrapped his arms” around United’s corporate side. Richard Arnold, the former chief executive, reported to Woodward, not Gill, when he joined as commercial director in 2007.

The Glazers only ever explained their intentions in one meeting with all staff. “They said, ‘Look, we’ve bought this club because we saw an opportunity’,” says a former executive. “They never came with, ‘We are fans of the club forever and always will be’. They didn’t claim to be anything other than businessmen and they are very good at what they do.”

Other figures well-versed in football marketing offer a different view. Edward Freedman was described as one of United’s most important signings of the 1990s by former chairman Martin Edwards. As managing director of merchandising, he took United’s merchandising operation from a turnover of £1.2million in 1992 to £28million when he left five years later.

Freedman is scathing of the approach taken by the Glazers. “They haven’t got a clue what a brand is,” he tells The Athletic. “It’s a very clever money-making move for them to get those deals. However, I’m sorry to say that, as far as enhancing Manchester United, it doesn’t work.”

United became associated with Japanese noodle firms and Indonesian tyre manufacturers, while players did promos holding out Mister Potato crisps. One high-profile agent privately complained that the club was “obsessed with commercialism” and “one big money-making machine”. After arriving back in the early hours following a match at West Ham United, some stars were required to drive mini kids’ Chevrolets in a sponsored stunt the next day instead of resting.

“I really can’t deal with it,” Freedman says. “We were offered all that long ago and never would accept any of it. Not for all the money in the world. Then, of course, the people who understood the brand left and people came in who saw only the recompense of taking money.

“But taking money for things that aren’t compatible with your brand will eventually ruin your brand. That’s what I can see them doing. The whole charisma, the whole glory of Manchester United, seems to have gone.”

Advertisement

Ben Hatton can remember “pouring scorn” over the Glazers’ approach while relaxing with colleagues in the pub after work but since leaving United 13 years ago, his opinion has changed. He says: “Actually, working a lot more in American sport, they are a different breed. The business of sport in the U.S. is exactly that: it is a business. That is why their sports franchises are, in the main, sustainable and ours are not.

“They do have that focus to say, ‘That is a pretty good business idea and, you know what, if you take a step back out of the parochial view on English football, it is a great idea’. If Manchester United score four goals at Old Trafford, who is not going to bid for the four balls?

“There were a lot of ideas like that and I often look back and think it must have been so very frustrating in the early days for these guys, looking at us little English folk from a northern town running what was, at the time, a small business.”

Supporters, including Walsh and Bones, would strongly argue that football clubs are community assets rather than franchises as in the U.S., but United’s focus off the pitch had already turned towards the balance sheets before the Glazers arrived.

When the Glazers came in, United had been trying to streamline their sponsors, not expand them. “We had our main relationship with Vodafone and eight platinum partners,” says a former executive. “But we actually wanted to go in a more strategic, ‘fewer but bigger’ direction. Instead of having eight sponsors at £1.2million a year, we’d have four at £5million. But they weren’t into any of that.”

Another director says: “They came with a view which was, ‘There are hundreds of companies in the world you’ve never heard of, all of which would be prepared to pay 10 times more than your current sponsors, so we are not really in the market to cultivate. We are looking to take the best offer on the table’.”

However, the line would be drawn at some companies whose ethical values “were not compatible”, such as payday lenders, even if the numbers were higher.

Woodward with Joel and Avram Glazer at the NYSE (Dario Cantatore/Getty Images via NYSE Euronext)

To begin with, Woodward and Arnold worked together on these sales deals in a small office in Mayfair. Arnold had known Woodward for many years but his suitability for the role quickly became apparent. “He won’t leave the room until he gets the answer he wants,” says one person familiar with his way of working. That mentality spread to his staff, and one worker even followed the equivalent executive at a potential sponsor on a family holiday to Bali to get the contract signed.

Advertisement

Joel, Avie, and Bryan paid keen attention to progress, leaving Gill to immerse himself in the football side and the brothers then committed to a bigger space housing 40 to 50 employees in Pall Mall at an annual rent of £5million. The entire marketing budget had been £600,000. “Sanctioning that was a ballsy move. It was probably the biggest sponsorship salesforce in London,” says an insider.

United’s London headquarters expanded again to Green Park, while a Hong Kong office was opened to cater for Far East customers. It is an approach that was followed by Liverpool and Manchester City, although United’s commercial numbers have flatlined for several years.

In the beginning, some staff suspected the Glazers “decided everything around the family dining table” — a view established when Darcie’s husband, Joel Kassewitz, attended board meetings, and fuelled further after Kevin Glazer was given the job of updating the club website from its 2005 version despite never showing any interest in United. There was talk of getting Microsoft or Apple involved but it didn’t change until 2018. In the same period, Manchester City had upgraded theirs on four occasions.

Raising ticket prices was part of the Glazers’ initial strategy.

In documents relating to their 2006 refinancing, they outlined their belief that tickets at Old Trafford remained “undervalued” despite having implemented increases of 12.5 per cent on average in their first season in charge. In particular, they suggested that United’s ticket prices were too low compared to those at the various London clubs and that “while Premier League teams in the north of England have historically been viewed as having a lower-wealth fanbase”, the club’s research showed that “the perceived gulf in fan wealth is not enormous”. Their projections included a further 36 per cent increase by the start of the 2012-13 campaign. “They introduced theatre-style pricing,” as one director described. “The better the view, the more you pay.”

United froze general admission ticket prices between 2012 to 2023 and that, in part, explains why annual match-day revenue plateaued at around £115million.

Those attending games were thankful for the club resisting rises but a persistent complaint was a lack of renovation on the stadium itself. Although the Glazers were, in part, mistakenly credited with the decision to increase Old Trafford’s capacity to 76,000 by developing the north-west and north-east quadrants of the stadium, planning permission and construction contracts were already in place before the takeover. Sir Roy Gardner, the plc chairman, stated in 2005 accounts that the estimated £43million costs of the development would be paid back within six years. As it transpired, with the Glazers raising ticket prices, it was repaid far quicker than that.

Advertisement

“It certainly was our aspiration to do more with the stadium,” Hatton says. “They seemed to pick that up early on and share the view it should be one of, if not the best, stadiums in the UK.”

Another person says, “When they first came, they had the intention of rebuilding Old Trafford. They were desperate to buy up all the land around the ground. And the only bit they didn’t buy was where Gary Neville and co put their hotel, and nobody thought you could do anything with that scrap of land back then.

“But they have given up on the stadium. I think they realised the cost, probably £1billion, is too much to justify. It’s not like the Emirates or Tottenham, where you can sell boxes for big money — there just isn’t the market for that in Manchester. But their neglect of Old Trafford is still very disappointing.”

Twenty years on, it is Ratcliffe and INEOS who are driving the project to build a new Old Trafford.

Back in 20210, the green-and-gold campaign was a visceral show of protest inside the stadium, one which was reprised in 2021.

Fans wave green-and-gold scarves in protest against the club’s owners in 2010 (Martin Rickett/PA Images via Getty Images)

The ‘Love United Hate Glazers’ motto was plastered around Manchester at the time but in truth, the Glazers were unperturbed by stickers, scarves, or songs. The only meaningful intervention to their ownership could come from a takeover bid and for a fleeting few weeks, that seemed a genuine possibility when a group of wealthy United fans gathered as a consortium to make an approach. The Red Knights were serious businessmen but did not get very far with the Glazers.

“Once everyone started talking about them, the Glazers upped their price,” says one person familiar with the matter. “Their strength was that there were 50 of them — there were some big players that the media never found out about — and they were philanthropic. But that was also their weakness.

Advertisement

“There were a lot of egos and some were more up for it than others but they all had a limit as to how far they would go. The Glazers made it very clear that they wanted more than the group were willing to pay and that was it.”

After the failed bid, one member told a friend: “It really depresses me. They’re the bane of my life and it’s probably my biggest failure. I failed to get these awful people out of the club I love.”

When the Red Knights formed, the Glazers still had an estimated £220million owed on the personal PIK loans used to take over the club, accruing interest at a punitive rate of 16.25 per cent. But that pressure was alleviated in November 2010 when Joel wrote to lenders to say the outstanding balance would be paid back within seven days.

People familiar with the industry say the Glazers were “very fortunate” to benefit from the timing of the credit crunch, which eventually encouraged the global economy to lend at low interest, but they did have to hold their nerve through the 2008 crash.

The Glazers’ status at United has been solid since the 2012 public offering (IPO) launched on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE). Once banks bought shares, it gave validation to their model and crystallised a value vastly in excess of the takeover price. On the first day of trading, shares closed at $14 each, valuing United at $2.3billion.

The Glazers initially intended to float the club in Hong Kong or Singapore in late 2011 but City of London sources say those plans were shelved by a combination of the exchanges wanting full financial disclosure, discomfort over the Glazers’ proposal to take most of the proceeds, and a lack of buyers at the kind of price they had in mind. This led them to the NYSE, then eager for new companies, and a modest sale in the summer of 2012.

Having once hoped to tempt Asian investors to part with more than £600million for the privilege of being associated with United, the Glazers had to settle for £150million in New York, half of which they banked. The rest was used to pay off some of the takeover debt they had put on the club’s books.

Advertisement

Many fans thought all of the proceeds should have gone to the club. But the original plan was for the Glazers to take the entirety. The NYSE expressed reservations, forcing a rethink, while people familiar with the industry describe the whole process as “problematic”. United say there were “zero issues” with the NYSE.

The flotation itself was a mixed bag as the share price debuted at $14, below the target range of $16 to $20. But that still represented a significant profit for the Glazers at very little cost in terms of transparency. Classed as an “emerging growth” company, United were exempted from having to reveal all their financial data to the market, a position they reinforced by moving the company registry from Old Trafford to the Cayman Islands.

As United’s annual reports noted, a company registered overseas is not required to follow the standard corporate governance practices of the NYSE. “Accordingly, we follow certain corporate governance practices of our home country, the Cayman Islands,” the reports stated. “Specifically, we do not have a board of directors composed of a majority of independent directors, or a remuneration committee composed entirely of independent directors.”

The Glazers were into a new, more secure phase of ownership. “The war was lost,” sighs one United campaigner.

Other contributors: Adam Crafton, Matt Slater, Oliver Kay, Daniel Taylor

Tomorrow: What next for the Glazers at Manchester United?

(Main image: Henry Cooke and Alice Devine)