When doctors at the Royal Liverpool University Hospital switched off the ventilator that had been keeping Paul Smith alive, his condition was so desperate that he slipped away within a minute.

His wife, Marie, held a phone close to his ear, not really knowing whether he could hear his favourite song, or as she puts it, “the only song he knew”.

Advertisement

In her soul, Marie remains an Evertonian and she’d never liked You’ll Never Walk Alone because of its attachment to Liverpool, her team’s local rivals and the team Paul supported all his life, but it has since taken on a different meaning. “I get upset now because it’s poignant,” Marie admits.

Paul died in April 2020, aged 52, an early victim of the Covid-19 pandemic that claimed around 2,000 lives in Liverpool alone. Not a day goes by that Marie and her daughter, Megan, do not think of Paul, and the past few weeks have felt especially bittersweet.

Liverpool’s Premier League win has been a source of jubilation in the red half of the city, especially as the club’s previous title — secured a few months after Paul passed away, with the pandemic still raging — was played out to a backdrop of empty stadiums.

On Sunday, Anfield will salute its heroes for the trophy lift after the final game of the season against Crystal Palace. The following day, more than half a million fans are expected to throng the streets for a parade.

Yet, for Marie, Megan, and others like them whose loved ones were denied the chance to see their team crowned champions of England once again, it will stir painful memories.

“I’m made up we’ve won the league, but I’m constantly thinking, ‘Oh, he’d be doing this now, or he’d be saying that, and making sure he had the day off for the parade’,” Megan says. “His flags would be out. A flag on the front door and a flag on the nearest lamppost. Instead, we’re planning on putting flags on his grave.”

Football was, in many ways, the making of the Smith family.

When Paul met Marie in 1993, he was working as an exit steward at Anfield. There, by the famous Kop stand, he saw her performing her duties as a volunteer police officer. Marie remembers going home and telling her mum she’d been asked out on a date. Though Marie had accepted, she wasn’t sure whether to show up, but her mum insisted she go. “How would you like it if it was your own son?” she argued.

Advertisement

After they married three years later, they lost a child, and Megan, born in 1998, was six weeks premature. She would develop a close bond with her father. As far as football was concerned, she was only ever going to support one team.

Paul eventually got a job greeting guests as an attendant on the doors of Anfield’s corporate lounges. He regarded the task of meeting and, in a few cases, getting to know some of the most decorated figures to represent his club as a privilege. Megan thinks they liked him because he’d talk to them like ordinary people about day-to-day matters. If he discovered any secrets, he certainly didn’t share them.

Paul stepped away from stewarding in 2017 — around the time Megan continued the family’s association with the club by becoming a tour guide at Anfield — because he wanted to be a fan again. Paul’s hero was Bill Shankly, but his daughter thinks he could see what was coming under Jurgen Klopp.

Paul Smith was a lifelong Liverpool supporter (Megan Smith)

Sometimes, Paul would be invited back into Anfield’s Carlsberg Lounge and Megan went with him on one occasion. She did not know then, but it was the last time she saw a live match with her dad. “Liverpool lost and my dad wasn’t happy,” Megan says. “I wish I’d paid more attention.”

Paul tended to mark Liverpool’s achievements by teasing his wife — “He loved winding up Evertonians,” Marie admits — and when the club won the Champions League in 2019, the house was decorated in flags. Megan can remember her dad telling her that the first league championship in 30 years was next, and he was right.

Liverpool became champions in June 2020, but Paul did not live to see it. Two months and two days before the title was confirmed, on April 23, 2020, he passed away from Covid-19 after becoming ill just three weeks earlier. Megan and Marie agree they have not come to terms with the absence of the man they adored. “We never will,” says Marie. “We have just learned to live around it.”

Advertisement

Events can be triggering, including Liverpool’s recent title win. Megan thinks it was easier to avoid getting caught up five years ago because of the lockdown restrictions muffling celebrations across the city, but this time, watching thousands line the streets of Anfield, the fireworks and the fervour, was just too much.

Paul, she feels, should have been there to see it, too.

Richie Mawson, another Liverpool fan, died a week before Paul in Liverpool’s Aintree hospital, not far from the course that hosts the Grand National horse race.

The two men did not know one another, but they had spent their adult lives obsessed with the same football club, living only a couple of miles apart.

The geography is significant because the Anfield area of Merseyside became one of the key landing stages for Covid-19 in Britain, thanks to the decision to allow Liverpool’s Champions League last-16 tie with Atletico Madrid on March 12 to go ahead in front of a capacity crowd of 52,000, including 3,000 travelling fans from Spain.

Madrid had already been placed into severe lockdown restrictions, with matches in the city having been staged without fans the previous weekend. The arrival of such a large influx of visitors meant districts such as Anfield and nearby Vauxhall, where Paul was from, and Kirkdale, the area Richie was connected to since birth, became breeding grounds for the virus.

The timeline leading towards their deaths suggests it is unlikely they became unwell as a direct consequence of the fixture, but as a wave of illness swept across the region, they were in its path.

Unlike Paul, Richie had attended the Atletico match. His son Jamie can remember discussing with his dad what was happening in Spain and Italy, where television footage was showing body bags piling high outside hospitals.

“He’d be on the phone to me saying, ‘Should this game be going ahead?’. I said, ‘Dad, I don’t think it should be, but you’ve just got to follow what they believe is right’.”

A fan wearing a mask at the Liverpool-Atletico Madrid game in 2020 (Simon Stacpoole/Offside/Offside via Getty Images)

Richie, who was 70 when he died, was a retired train driver. He was, according to Jamie, a typical Liverpudlian: “He loved his family. He loved a bet. He loved going out with his mates for a pint. He also loved his holidays in Spain. But his passion was Liverpool FC.”

Richie had been following the club for 63 years, starting when the team was struggling in the old second division. Within five years of Jamie’s birth in 1972, he had a son to take with him, and together they travelled all over Europe.

Advertisement

Like Paul, Richie had been at Hillsborough in 1989 when 97 Liverpool supporters were killed at an FA Cup semi-final due to institutional failures of the authorities overseeing the match.

Richie and Jamie, then aged 16, were relatively safe in the upper tier of the Leppings Lane stand, but getting there had been terrifying. Outside, Jamie had witnessed the congestion and the screams of fans, begging the police to do something about it.

They made it in and as Richie went to the toilet, Jamie was waiting near the gangway, just as a gate was opened and hundreds of fans rushed in. Jamie positioned himself next to a wall and remembers his dad suddenly appearing, shouting, “Jamie, Jamie!” Richie battled his way through the crowds, stopping his son from being swept away into an enclosure where so many would lose their lives.

Richie Mawson and his wife, Mary (Jamie Mawson)

Jamie has never forgotten what he witnessed from his position above the death trap. As men, women and children were lifted towards him as they tried to escape the crush, Jamie and his dad started crying. “What happened will stay with me for the rest of my life.”

Despite that trauma, Richie did not lose his love for football, and certainly not for Liverpool. Most of all, he loved European nights at Anfield, so when the UK government gave approval for the Atletico game to take place, he was not going to miss it.

Liverpool lost 3-2 that night, ensuring their elimination from the competition, and afterwards, Richie called Jamie from the Dark House, his favourite pub back in Kirkdale.

Richie sounded concerned even though he had worn a mask. An hour or so before kick-off, the World Health Organisation had declared a pandemic. “I told my dad it was better to get home than stay in the pub,” Jamie says. “I said to him, ‘You’ll be OK… you’ll be OK’.”

Steve Rotheram, Labour’s metro mayor for the Liverpool city region, had been sitting near Richie in Anfield’s Sir Kenny Dalglish Stand. He was also in two minds whether to go, but decided to follow the official government guidance, which meant sanitising his hands repeatedly as he sat in the back of a cab on the way to the ground.

Later in the pandemic, Rotheram would play a prominent role in Liverpool’s response to the outbreak, but at that point he was not statutorily responsible — still a source of frustration today as, in his words, it left regions such as his “blindfolded”.

In 2023, an inquiry into Britain’s response to Covid-19 found that the country was ill-prepared for a pandemic after more than a decade of cuts under successive Conservative governments. In that inquiry, Rotheram complained that nobody in a position of authority on Merseyside or the neighbouring Wirral area was consulted when the UK government decided, in February 2020, to place British nationals living in the Chinese city of Wuhan, where the first cases of the virus were recorded, in a secure unit at Arrowe Park Hospital, on the other side of the River Mersey from Liverpool. It was, in Rotheram’s view, a sign of things to come.

Advertisement

“Those significant decisions that were taken on behalf of us all had really terrible and disastrous consequences for some families who still now are absolutely convinced that their loved ones died of Covid-19 because they attended a football game,” Rotheram tells The Athletic.

On the day of the Atletico game, Liverpool had six confirmed cases. By April 2, the figure had risen to 262. A month later, Liverpool had one of the highest death tolls in the UK outside of London: Paul Smith and Richie Mawson were among the 303 people to have succumbed to the virus.

Liverpool celebrate their title win at an empty Anfield in 2020 (Laurence Griffiths/Getty Images)

For Jamie, the loss of his father continues to feel raw. He was an only child and he thought of his dad as his best mate. From his home in Formby, he used to pop into his parents’ place in Kirkdale before walking to Anfield with his dad. He misses strolling through the park and going for a pint with him on his way to the ground, before repeating the routine on their way home.

They used to have season tickets right next to one another, but since 2020, Jamie has not returned to his seat and he will not be at the stadium on Sunday for the trophy lift.

“It’s very, very hard just to go, either with a mate or even with my daughter,” he says. “My dad and I sat together, we hugged, we cried, experiencing every single emotion together. And then I just cannot for the life of me at this moment in time drag myself up the ground because I’m thinking, ‘Where is he?’.”

It was only a few days after attending the Atletico match that Paul Machin began to feel unwell.

Machin, a host on the popular Redmen TV YouTube channel, remembers going to a supermarket to help prepare for his cousin’s birthday and having a sense that something was creeping up on him, but hoped that paracetamol and vitamin supplements would snuff it out. At the party that followed, he found out that his pregnant sister was experiencing the same symptoms.

Advertisement

Lockdown was still four days away when, on March 19, Machin posted a video on YouTube to explain what was happening to him. His sister had since tested positive for Covid-19 and he was feeling horrendous, describing the “worst flu imaginable” with a shortness of breath thrown in. He was struggling to take in lungfuls of air and a trip to the bathroom became an ordeal because a few steps were so exhausting.

Just when he was beginning to feel a bit better, the virus returned, hitting him like a “tonne of bricks — that’s when you realise how serious it really was, because I was totally, totally wiped out”.

Paul Machin suffered the effects of long Covid (Simon Hughes/The Athletic)

Machin says he has not quite felt himself since. He describes brain fog-like symptoms commonly cited by those who have suffered from long Covid, struggling to find words that used to come easily.

Machin has no doubt that attending the Atletico match caused him to become ill. He interviewed fans at close quarters before the game as part of his Redmen TV duties and recalls the euphoric celebrations on the Kop that accompanied each of Liverpool’s two goals, bodies piling on bodies, heedless of the wider dangers.

He was 37 in 2020 and considers himself one of the lucky ones. Older people, such as Paul Smith and Richie Mawson, were less fortunate, even though both men were in good condition with no underlying health conditions.

Paul’s wife, Marie, was already aware of the virus’ dangers because she was a supervisor at the accident and emergency unit in the hospital where her husband ultimately met his end. She was there when the first person was admitted with Covid-19, wearing her face mask and apron. It was her job to oversee the cleaning of the lift after the patient was rushed into a secure ward where doctors were covered in personal protective equipment.

Marie still has the letter that confirms Paul — who had taken a part-time job as a cashier at a supermarket in Aintree — was considered an essential worker. When he began complaining of tiredness, the family thought he was simply exhausted from the long shift patterns: he was often up at 4am, arriving at work an hour later. Across those early weeks of the pandemic, he would sometimes not return home until 8pm, as panic buying gripped the city.

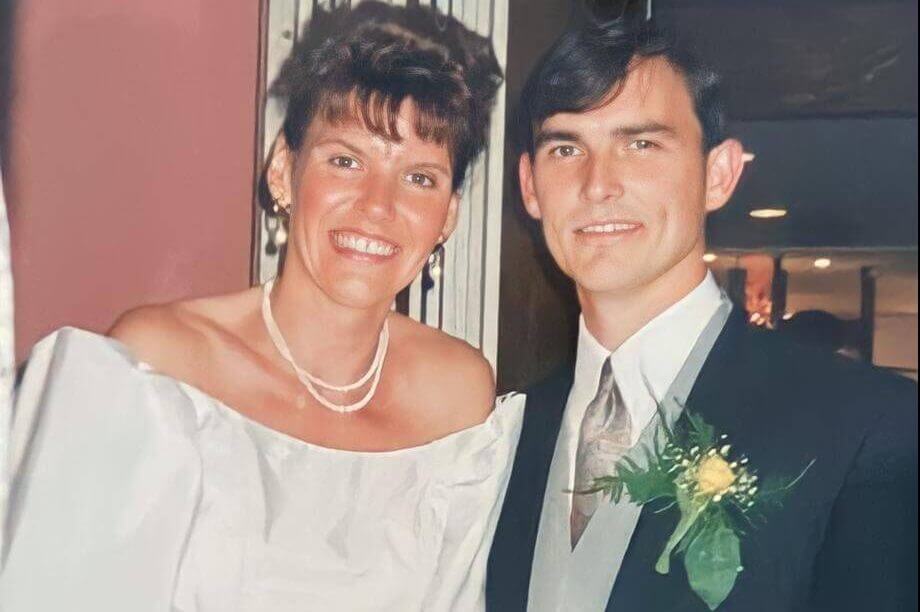

Paul Smith and his wife, Marie, on their wedding day (Megan Smith)

On April 1, Paul started displaying symptoms of Covid. After being told to isolate in a separate room, he was admitted to hospital on April 5 after telling Marie he could not breathe. Less than 24 hours later, he was placed on a ventilator.

When Megan entered the ward where her dad was about to die, she was advised by nurses where to look. On one side, there were makeshift cubicles made out of plasterboards. There were barely enough curtains to give people attached to ventilators some privacy. “They were completely out of it,” she remembers. “I don’t know how the staff did it. It was like a war zone. It was awful.”

Advertisement

The doctors had spent the previous hours turning Paul from his back to his front to see whether they could get more oxygen into his lungs, but his condition was worsening.

Marie thinks he made it through the previous weeks because of video messages from legendary Liverpool players such as Steven Gerrard, Jamie Carragher, Bruce Grobbelaar and David Johnson. “The doctors and nurses made sure he passed away with dignity and respect, and I will forever be grateful to them,” Megan says.

It was a different experience for the Mawson family, who could not enter the hospital where Richie was losing his fight for life.

Jamie wanted to protect his mum from what was happening. After a telephone conversation with his dad, he knew he was struggling. From then on, updates went through Jamie. For a week or so, he was told that his dad was “comfortable”, but Jamie knew that meant he was not improving.

When Jamie was told by a doctor there was nothing else he could do to save Richie, he begged him to carry on trying. “I told him: ‘Just give him another week’,” Jamie says. “The doctor said that he’d been in hospital for almost a month without responding to any treatment. He said: ‘I’ve got no option, I’m going to have to turn the machine off’.”

Jamie and Mary said goodbye to Richie through a video call, with a nurse holding the phone up to him, before the machine was switched off.

“I asked the nurse to hold his hand because we were not allowed to be there. He looked bloated and swollen because of the steroids. I’m screaming, crying my eyes out in front of this poor nurse. She said, ‘Don’t worry, Jamie, I’m not going to leave him’, but we had to end the call. We were uncontrollable.”

When Liverpool won the Premier League title on June 25, 2020, two months after Richie Mawson’s death, Jamie and Mary marked the occasion in Formby by raising a glass of champagne to the man they loved.

The day before, when Liverpool returned to Anfield for a game against Crystal Palace for the first time since the season was interrupted, a steward’s jacket with Paul Smith’s name on it had been placed on the Kop in his honour.

A steward’s jacket bearing Paul Smith’s name is laid on the Kop before the game against Crystal Palace in June 2020 (Andrew Powell/Liverpool FC via Getty Images)

The club’s former steward used to call his daughter his “shadow”. Megan says it’s the little things she misses the most about her dad: asking if she was OK as she walked past where he was sitting on the couch, walking through the front door after work, or his text messages.

“To some people, they might seem like little things, but to me they are massive,” she says. “If I ever felt worried or anxious, I’d always go to my dad. If I ever thought I didn’t know what to do or I needed advice, it’d be my dad.”

Advertisement

Megan is grieving her loss and has been diagnosed with PTSD because of some of the things she saw in the hospital as her dad passed away. She says she is plagued by thoughts about how he contracted Covid-19. Was it because of her? Though it seems very unlikely, she will never know for sure.

What she does know is how her dad would have reacted to Liverpool’s latest title triumph.

“It just feels so unfair,” she says. “He’d want Liverpool fans to celebrate it properly because he was such a mad Red. But then he’d also say, ‘Remember us, the ones who didn’t make it; remember us when you’re having a pint’.”

(Top photos: Courtesy of the Smith and Mawson families; Getty Images; design: Dan Goldfarb)