As Dan Ballard rose and Coventry City sank, Wearside detonated and the stage was finally set. Ballard’s Sunderland will now play Sheffield United in the Championship play-off final on Saturday afternoon at Wembley Stadium in London for a place in next season’s Premier League — and the riches that come with it. The teams will be contesting the single most lucrative one-off game in world football.

Advertisement

United’s semi-final was much less dramatic, their 6-0 aggregate victory against Bristol City being the most lop-sided play-off win in second-tier history. Chris Wilder’s side finished the regular season in third place with 90 points, only the third team ever not to be automatically promoted with that many.

The trendsetters in that regard are Sunderland, who racked up the same number in 1998 before falling at the final hurdle, losing a penalty shootout 7-6 at Wembley after a wild 4-4 draw with Charlton Athletic. It’s still considered by many the greatest play-off final ever. This weekend brings Sunderland’s first Championship play-off final since that day 27 years ago.

A look at the recent histories of the two clubs shows almost opposite journeys to this season’s denouement, both on the field and off it. United were a Premier League club last season, and for the two years before that; Sunderland haven’t played in the top tier since 2017, when relegation followed 10 straight years in the division — in none of those years were they joined among the domestic elite by the side from the red and white half of Sheffield.

Accordingly, the finances of the pair have diverged.

Back in 2016-17, Sunderland generated a club-record turnover of £126.4million even as they finished bottom of the Premier League. United, then playing two divisions below, earned just £11.6m while finally getting promoted from League One at the sixth attempt.

Eight years on, it is United in the ascendancy. Last season, they booked revenues of £138.2million, once again showing the lucre that falls from the sky in the top division, even if you’re the team in its basement. Sunderland, despite being one of the higher earners in the Championship, earned £100m less.

The gap has narrowed in 2024-25, but the order remains the same. Sunderland’s income has ticked up, owing to increased ticket prices and via the EFL’s improved TV deal, which began this season; Championship clubs pocketed £5.4million from that agreement this year, up from £4.0m. Sunderland, along with 19 other sides in the 24-team division, have also banked £5.3m in solidarity payments from the Premier League.

Advertisement

That pales in comparison to United’s takings from the division they tumbled out of meekly just one year ago. Their presence in the Premier League entitled them to a £49million parachute payment this season, an amount on its own that’s more than the total income of any Championship club not getting parachute payments.

If United lose at Wembley, they’ll get at least £40million via a second-year parachute next season, and probably more given the new Premier League TV cycle kicks in come August. If Sunderland are the beaten side, they’ll continue to receive only the solidarity payment from the Premier League, equal to just 13 per cent of a second-year parachute.

United’s income dwarfed Sunderland’s last season, though only via their Premier League status and the attendant broadcast income. Sunderland’s matchday and commercial revenues eclipsed United’s, despite playing a division below them. Both of those streams were driven by the size of Sunderland’s fanbase; the Wearside outfit’s average attendance in 2023-24 was over 11,000 higher than United’s, and the gap has widened in the current campaign.

Perhaps a greater surprise is Sunderland’s net transfer outlay in the past three seasons — while their total is only £ 8.9 million, that is higher than United’s. Sunderland are hardly big spenders in the great scheme of things — their squad cost of £18.4m to the end of July 2024 was only mid-table for the previous season’s Championship — but United’s lowly net spend reflects their recent history of bouncing between the top divisions: up in 2019, down in 2021, back up two years later, then instant relegation. They have sold players for decent sums, and did so this season; the moves of Cameron Archer, William Osula and Daniel Jebbison to Premier League clubs helped generate £22.3m profit last summer.

Sunderland, who suffered a second straight relegation in 2018 before being promoted back to the Championship three years ago, have shifted to their own player trading model, raising money from selling Ross Stewart, Jack Clarke and, just recently, academy graduate Tommy Watson. The club’s lowly squad cost reflects a policy of buying low and selling high.

Still, despite the low recent net spend, United’s squad, built to try to survive in the top tier, had cost £100million more than Sunderland’s at the end of summer 2024. Their wage bill was more than double Sunderland’s last year too, though it has likely reduced this season.

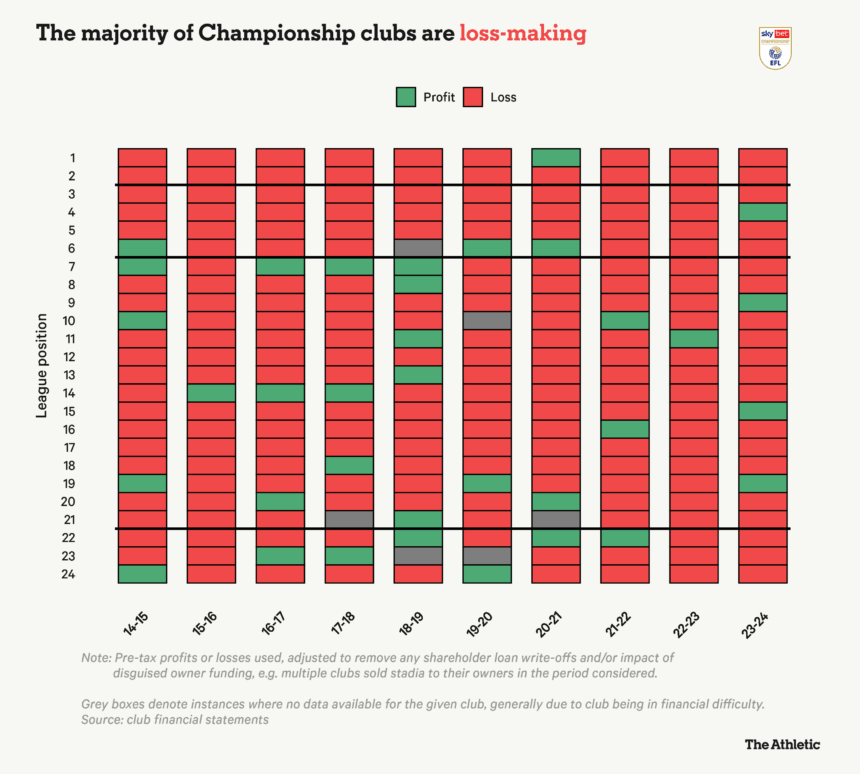

As well as the prestige of Premier League football, there’s a fairly obvious reason why clubs strive to get out of the Championship: hardly any of them make money at that level.

In 2023-24, just four of the division’s teams managed a profit. Two of those — Southampton and Watford — had the benefit of parachute payments. The other two — Coventry City and Blackburn Rovers — only made their way into the black by selling players; Coventry brought in good money for Viktor Gyokeres and Gustavo Hamer (who’ll play for United in this final), while Blackburn’s sale of Adam Wharton to top-flight Crystal Palace saved them from a third consecutive eight-figure deficit.

In all, the 24 Championship clubs lost £321million last season — almost exactly the same as 2022-23’s division-wide loss.

Across the past 10 years, pre-tax losses in the second tier total £2.805billion, or roughly £11.7m per club per season. That figure only worsens when we consider several of its teams enjoyed owner loan write-offs and intra-group asset sales which boosted bottom lines.

Stripping those elements out paints a bleak picture. Of 234 clubs for whom we have data over the past 10 Championship seasons, only 35 were profitable. That’s just 15 per cent.

And those profitable clubs were far more likely to wind up near the bottom of the table. Over a third of the 35 have finished in the bottom six, and 20 per cent of them were relegated. At the other end of the table, just one — Norwich City in 2020-21 — managed the feat of going up automatically while banking a profit. Beyond them, four clubs in the 10 years managed to earn a play-off spot without losing money.

Advertisement

Part of that is linked to the fact teams agree to pay promotion bonuses, knowing the riches that will soon be due to them in the Premier League. Those can sometimes be the difference between profit and loss. Yet the overall picture is clear. The Championship is a wildly loss-making division and one in which, as we’ll see, member clubs need substantial backing from their owners just to compete.

With this season being the second in a row where all three of the Championship’s promoted clubs have come straight back down, there’s been much discussion around the growing gulf between the top two divisions. Yet an overview of its finances points to an argument that, much like its bigger brother, the Championship is breaking up into leagues within a league.

A comparison of recent turnover and wages is instructive.

On both metrics, recently relegated clubs dominate matters. Parachute-payment clubs have long dominated revenues, but last season saw the gulf widen; both Leeds United and Leicester City racked up over £100million in turnover, with Leeds setting a new Championship record.

As has been the case for a long while, the top spots in terms of revenue are all populated by clubs in receipt of parachute money. Leeds, now automatically promoted, have received £40million that way this season. Based on the most recent figures, the only non-parachute Championship club with total revenue in excess of that were play-off semi-finalists Bristol City.

Four clubs enjoyed parachute payments this season, and a Sheffield United victory would ensure all three promotion spots went to such recipients. In each of the previous six seasons, two of the three promoted sides received parachutes. Luton Town, relegated for the second year in a row on the final day of this campaign, firmly bucked a trend of recently-relegated clubs being among those most likely to make an immediate return to the Premier League.

Correspondingly, the wealthiest clubs spend the most on wages.

Advertisement

Leicester’s £107.2million wage bill last season was a new second-tier record (Newcastle United’s £112.2m in 2016-17 included over £20m in provisions for future wage payments) and between them, the three relegated clubs (Burnley, also promoted this month, were the third) spent £272.1m on wages. Ten seasons earlier, the combined wage bill of the division’s three highest paying clubs was less than half that (£127.1m).

The problem for the rest is that without spending beyond their means to keep up, their already slim chances of promotion disappear entirely. High wage costs explain why nobody in the division makes a profit, even while most are only paying a third, or less, of those at its top end.

In 2023-24, 12 Championship clubs, half the division, spent more than their turnover on wages alone. It was the same a year earlier. Since 2014-15, 136 out of 232 second-tier sides for whom we have data spent more than their annual income on wages, before any other costs of running their operation came into play. Reduce the checkpoint to 70 per cent — long held up as a “healthy” wages to turnover ratio — and only 31 of its clubs (13 per cent) came in under that mark.

Remarkably, having 12 of 24 clubs with over 100 per cent wages to turnover is an improvement. Not since 2014-15 had that particular count been so low and, on an overall basis, the Championship’s wages to turnover hit 93 per cent in 2023-24, the lowest mark since 2011-12.

That’s still worryingly high, especially if teams are striving for sustainability. Yet few are. It seems to be taken as written that achieving promotion to the Premier League will come at a high cost and, in the meantime, clubs (or rather, their owners) just have to bear it and hope.

Ipswich Town won automatic promotion last season with a wage bill of £44.5million, almost half that of the Leeds side they beat to a place in the top two; £15.6m of that, over a third, comprised promotion bonuses, making their feat even more impressive. Without that, Ipswich’s wages to turnover would have been a more respectable 78 per cent.

Ipswich, like Brentford and Luton before them, were able to get promoted with relatively low wage bills. Sunderland’s staff costs for this season are unknown, and they may fall into a similar category if they win at Wembley (particularly as they have higher non-player wages than many Championship clubs).

Advertisement

Promotion isn’t the exclusive prize of the biggest spenders, but they do generally sweep up the available spots.

In the five seasons before this one, 11 of the 15 teams to go up from the Championship have spent more than £50million on wages — and remember that no non-parachute club comes close to that mark in a revenue sense. On average, between 2019-20 and 2023-24, you had to spend £64.4m on wages to achieve promotion.

Wages as a proportion of income could improve further this season, on the back of the EFL’s new TV deal which, while far below the Premier League’s riches, should make a difference, particularly at the less wealthy end of the second tier.

A significant improvement for the Championship last season arrived in the guise of player sales. Across the division, the 24 clubs racked up player-sale profits totalling £420.4million, a massive increase on the two previous campaigns and, by £99m, a new divisional record.

That fails to tell the whole story, though. A deeper look shows up something startling: £228.5million (54 per cent) of the £420.4m was accrued by the three recently-relegated clubs. Of the remaining teams, sharing £191.9m in player-sale profits, 11 generated less than £5m.

That, again, points to the trend of clubs who’ve just come down dominating the Championship, on and off the pitch. On a broader level, the second tier has never been more profitable from player trading than during last season, yet that profitability was driven by the three sides who had been in the Premier League a year earlier. Where, last season, over half of player-sale profits went to those clubs alone, the figure in 2015 had only been a quarter.

With such high losses across the division, it’s evident that Championship clubs aren’t funding themselves. Unsurprisingly, debt in the division has ballooned. To the end of the 2023-24 season, the second tier’s gross debt was £1.588billion, more than double the £743.8m of 10 years earlier.

Advertisement

Debt is hardly an unfamiliar concept in English football; Premier League club debt was £4.738billion at the same point. Yet, while in at least a few instances we can point to top-flight sides building new stadiums or improving existing facilities, the same has rarely been true one rung down the ladder. Overwhelmingly, debt there has gone toward funding the dream of promotion.

The type of debt present in the Championship reflects as much. Of that £1.588billion, £1.227bn (77 per cent) is ‘soft’ debt owed to owners or related parties. Much of that is at low or no interest, and that doesn’t include the swathes of debt previously converted to equity.

Championship owners have funded their clubs to the tune of £3.258billion over the past decade, the equivalent of £892,000 per day, every day, for those 10 years. Much of that has gone toward underwriting day-to-day losses. Even after accepting we don’t have cashflow data for 11 per cent of teams over the decade, Championship teams lost £2.819bn in cash at the operating level. Over the same time period, including balance-sheet figures for some of those clubs without cashflow statements (and so reducing the missing data to just three per cent), the Championship’s members spent just £531.9m on infrastructure works.

The costs of competing in the second division are so vast that clubs are heavily into the red before they can even consider spending on capital projects. At the operating level, before player sales, sides in the Championship lost £5.143billion over the past 10 years. Last season’s combined operating loss — propelled in no small part by those huge wage bills at newly-relegated trio Leicester, Leeds and Southampton — was £683.1m, a divisional deficit only topped by pandemic-ravaged 2019-20 (£694.8m).

Transfer fees, amazingly, actually net out across the decade; on a cashflow basis, £2.300billion was spent on new players, while £2.299bn was recouped on sales. In other words, across the division, player trading has been neither a drain on resources nor a boost to them.

If you’re wondering how that tallies with the recent burst in player-sales profits, the answer lies in how most clubs pay for incoming transfers in instalments. With the bulk of player profits accruing to recently-relegated clubs, and those same sides increasingly being the ones nabbing promotion spots, it means some of the cash impact of chunky player sales made while teams are in the Championship won’t actually be seen until after they’ve returned to the Premier League.

Returning to this weekend, while the winners of the Club World Cup final in July will bank $40million (£29.8m) for that one victory, in an indirect sense the Championship play-off final is the best-paying one-off game in football — and by a long way.

A win this weekend will guarantee Sheffield United or Sunderland at least three years of elevated TV income, first in the form of central distributions while a part of the Premier League and then, even if 2025-26 brings immediate relegation, at least two seasons of parachute payments.

Advertisement

Quantifying the worth of coming out on top isn’t easy, particularly when the size of the Premier League’s overall TV deal keeps going up year-on-year. The identity of the finalists makes a difference too: Sunderland, who no longer receive parachute payments, will see greater future revenue gain than United, who do.

Yet even using a fairly simplistic measure — adding together however much the lowest-earning Premier League club got in the season of a given final, alongside two years worth of parachute payments, again based on the same year — gives a clear answer: winning the Championship play-off final now guarantees you at least £200million in broadcast income over the following three seasons.

Fifteen years ago, that figure was £57million; by 2015, it had more than doubled to £130m. In the past decade, the sum has gone up a further 54 per cent and, in reality, the worth of winning this final is likely even higher than that. Next season’s new TV cycle will increase club distributions further, improving the lot of this weekend’s victors both when they’re back in the top tier and even if they fall victim to another relegation in a year’s time.

Each will hope the latter doesn’t happen, both for financial and footballing reasons. Yet such worries will be a long way from minds as Wembley’s famous arch beckons this morning.

The most financially consequential game in football is upon us.

(Top photo: Southampton celebrate beating Leeds in last year’s Championship play-off final; Adrian Dennis/AFP via Getty Images)