Stadium redevelopment is the new frontline in the financial cold war between Premier League clubs and, as is customary for Liverpool’s owners, FSG have long been ahead of the curve at Anfield.

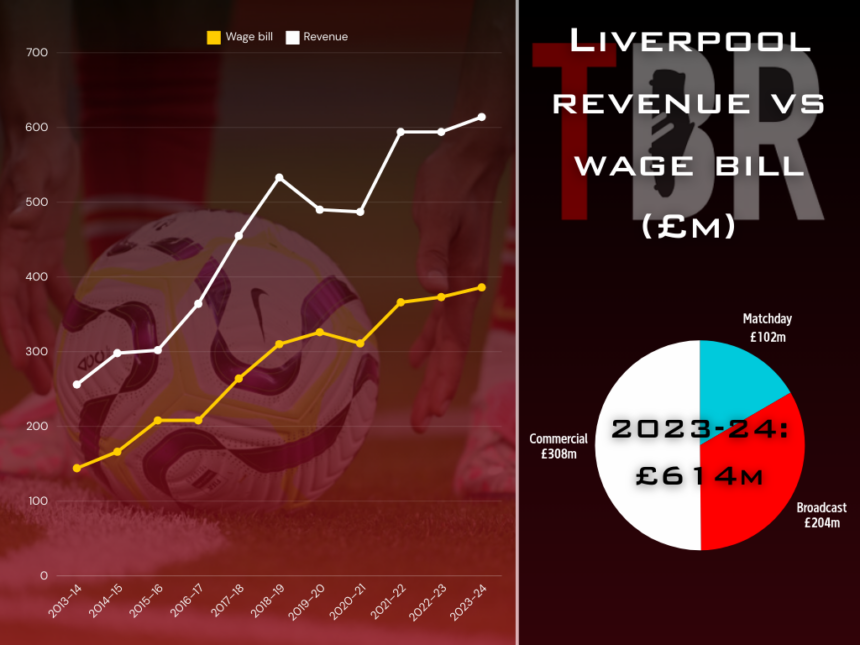

Liverpool’s matchday income is the most modest of their three revenue streams, with their commercial operation and centrally negotiated media deals making up about 80 per cent of their £614m turnover.

But the cash they earn through the turnstiles is growing – and fast. Even last season, when they had no Champions League football and its associated ticketing opportunities, it increased by £22m.

Photo by Michael Regan/Getty Images

Whether that’s good or bad depends on which side of the ledger you sit. And this dichotomy cuts through to the heart of the central debate in modern football finance: fan culture vs consumerism.

For Liverpool fans, the upwards trend in the cost of supporting their team is worrying, though the club have to their credit frozen general admission and season ticket prices for 2025-26.

But as far as Fenway Sports Group (FSG) are concerned, the resistance to rising prices is a major headache. In the past, John Henry has explicitly said as much.

They’d love nothing more than to turn Anfield into a Disney Land-style experience, trading on Liverpool’s IP to extract maximum value from more lucrative demographics than the club’s bedrock support.

That’s why pressure from supporter groups like Spirit of Shankly, who orchestrate the official Supporter Board set up in the aftermath of the FSG-minded European Super League, is so valuable.

This system of checks and balances is far from unique to Liverpool, but their status as one of the Premier League’s two biggest exports, alongside Manchester United, means its arguably more pronounced.

Photo by James Gill/Danehouse/Getty Images

There is, however, a trade-off which comes in tow with supporting one of the world’s most famous clubs, especially one with the self-funding model favoured by the owners five time zones away in Boston.

To keep up with inflation in the transfer ecosystem – as well as the wage market, as Liverpool have witnessed first-hand in Trent Alexander-Arnold’s contract psychodrama – revenues need to rise every year.

The Reds haven’t hit a ceiling with matchday income yet. They will realise the full financial benefits of the expanded Main Stand and Anfield Road Stand over the next few seasons.

But after that, there will be an inflection point as Henry, Tom Werner and their colleagues in the FSG hierarchy look to keep pace with a growing contingent of clubs with shiny new stadiums.

Man United are seemingly destined for Europe’s biggest and most lucrative arena, following in the footsteps of Tottenham with their move to a new money-printing stadium in 2019.

Man City are in the process of expanding, while Arsenal and Chelsea are set to embark on their own stadium projects in the next few years too.

Looking outside the so-called Big Six, Liverpool see uber-ambitious clubs in their rear view, backed by sovereign wealth or private equity funds for whom stadium expansion is the next step in the masterplan.

The likes of Aston Villa and Newcastle won’t catch the Merseysiders in this category. At least, not any time soon. But they will loosen the knots of the financial safety net Liverpool have enjoyed in the modern era.

So how do Fenway protect their position without alienating the traditional support who generate the atmosphere and culture that made the club such an attractive investment prospect in the first place?

Commercial income – that’s revenue from sponsorship, merchandise and events – has less of a defined ceiling than matchday but it’s a saturated market. And the tide is rising across the Premier League.

It’s hard to gain an outsized competitive advantage from media and TV rights too given that they are engineered at the Premier League and UEFA’s HQs, not at FSG’s offices in Boston or on Merseyside.

That’s why, despite the fact that bricks-and-mortar redevelopment is phenomenally expensive, matchday income is seen as the golden goose in football, and the space race is on to capitalise.

So what options are available to Liverpool?

They could surely satisfy higher demand for tickets – but is another expansion feasible, affordable, and cost-effective? And if not, how will Anfield continue to up the ante financially?

- READ MORE: Liverpool owners FSG get update on £4.7bn takeover battle as world-record deal agreed in Boston

Liverpool won’t expand Anfield – but there could be big changes

The idea of another expansion has been floated often in recent month in light of events in Manchester, but this week it emerged that Liverpool have not revised their stance on increasing capacity at Anfield.

However, while the number of seats might not change, the cash generative power of the stadium may well.

Clubs are increasingly looking to hospitality and retail to push the envelope. And on that note, Liverpool announced yesterday that they have submitted an application to refurbish their on-site megastore.

However, the real value might lie not with increased merchandise sales on matchdays but what Liverpool can do with their stadium when it isn’t in use by Arne Slot’s side.

Three Taylor Swift gigs last summer generated eight figures for Liverpool, while Bruce Springsteen, Lana Del Rey and Dua Lipa – an act with whom fans have an unlikely affinity – will play the stadium this June.

But Liverpool will soon have a new rival in this space, with Everton’s Bramley Moore Dock stadium purpose-built to stage concerts, alternative sports events, and more.

That may be the reason the Reds CEO Billy Hogan has opened up the possibility of the club applying to host more non-football events in the future.

“We think it is amazing that we can bring this calibre of artists to the city,” he told FC Business magazine in September.

“The more events we can host, the better for us anecdotally, but our priority is obviously to play football matches, so our calendar is extremely tight.

“Maybe we can put on events in early July in the future. We will have conversations about that, but the concerts have been an enormous success, all made possible by the progress we have made.”

More events at Anfield wouldn’t be trivial for Liverpool in financial terms – promoters pay big fees and, crucially, its extra income that would come from the pockets of concert goers, not Liverpool fans.

Hospitality and premium seats at Anfield: The next big revenue plateau?

VIPs, the prawn sandwich brigade, the champagne section – whatever you want to call them, premium and hospitality seats are big business at Anfield – and indeed across the Premier League – these days.

Most stadium expansion projects, Liverpool’s included, place proportionately far greater emphasis on space for high-paying guests than they do on reducing the season ticket waiting list.

There are even some elite clubs that generate almost as much revenue from premium seats as they do from every other area of the stadium combined.

Liverpool don’t offer a breakdown of their ticketing income – but TBR Football’s crude calculations show how much these seats bring up the average revenue per fan.

General admission adult season tickets at Anfield, which make up 50 per cent of capacity when combined with cheaper concessions ticket too, range from £713 to £904.

The average revenue per fan across the whole stadium per season is almost £1,700.

Granted, single issue tickets, which are more expensive on a per-game basis than season tickets, contribute to that discrepancy too, but hospitality is by far the biggest driver in pro-rata terms.

FSG miss out on potential £100m Club World Cup bounty

FSG value Liverpool at over £4bn, as demonstrated with their sale of a tiny three per cent stake to Dynasty Equity for around £127m in September 2023.

Photo by Nick Taylor/Liverpool FC/Getty Images

But how do they justify that appraisal when, even as one of the better performing Premier League sides when it comes to the profit-and-loss account, they have only just broken even since FSG’s takeover?

Are Premier League club valuations a speculative bubble, or are owners such as Fenway banking on a tectonic shift that will unlock huge revenues and make their investments consistently profitable?

One of the simplest ways to get more money in football is simple: more football matches.

The revamped Club World Cup is case in point. This summer, 32 teams, including Manchester City and Chelsea, will compete for the tournament in the United States, up from seven last time around.

FIFA’s drive to change the perception of this competition from a Mickey Mouse event to a prestigious quadrennial event that rivals the Champions League involves throwing a lot of money around.

The tournament’s TV deal – which is being funded by Saudi capital – is worth over £750m. The winner will bank north of £100m. Not bad given that the eventual victor will play just seven matches all told.

Liverpool missed out this time, but FSG have thrown their weight behind the new Club World Cup.

If they can secure qualification next time around and the tournament can justify its mammoth media deal, it could be one of the financial quantum leaps they’re looking for.