I am an FC fan

I am Mancunian

I know what I want and I know how to get it

I wanna destroy … Glazer and Sky

(To the tune of Sex Pistols’ Anarchy in the UK)

Through the double doors, then up the first flight of stairs, there is a framed shirt on the wall inside FC United of Manchester’s entrance that says a lot about the attitudes they encountered in their early days.

Advertisement

It is the red T-shirt the players wore after their first couple of league titles and it carries a quote from Alan Gowling, a BBC radio pundit, when FC were set up as a breakaway club for disillusioned Manchester United supporters in the summer of 2005.

“It won’t last until Christmas,” can look awfully silly, 20 years on.

In fairness to Gowling, he was not the only one — from Sir Alex Ferguson down — who viewed FC through suspicious eyes and underestimated, perhaps, the collective spirit of the people who built the club from scratch.

A reporter from the Manchester Evening News once asked Ferguson about FC’s first promotion under Karl Marginson, the fruit-and-vegetables delivery man who was appointed as the team’s first manager. “Not interested,” said Ferguson, immediately rising to get out of his seat. “Not interested!”

Or perhaps you remember the scene in Ken Loach’s 2009 film, Looking for Eric, when a long-time United fan is drinking in a pub with an FC supporter and they become embroiled in a beery argument about what led to the split.

“You can change your wife, your politics and your religion but never your football team,” the United fan lectures.

But the argument is won by the bloke in the non-sponsored FC shirt. “They left me,” he says — not the other way around.

It is 20 years on May 12 since the Glazer family took control at Old Trafford and a defiant group of fans, already disillusioned with the gluttony and commercialism of top-level football, decided enough was enough.

Everything they predicted about United’s American owners has become reality: rising ticket prices, neglect, divisions, a growing sense of detachment between the club and fans and some substantial evidence to justify the pre-takeover view of former chief executive David Gill that “debt is the road to ruin”.

Advertisement

Nobody at FC takes enjoyment from being proven right. How can they be happy when they are, at the heart of everything, old United fans?

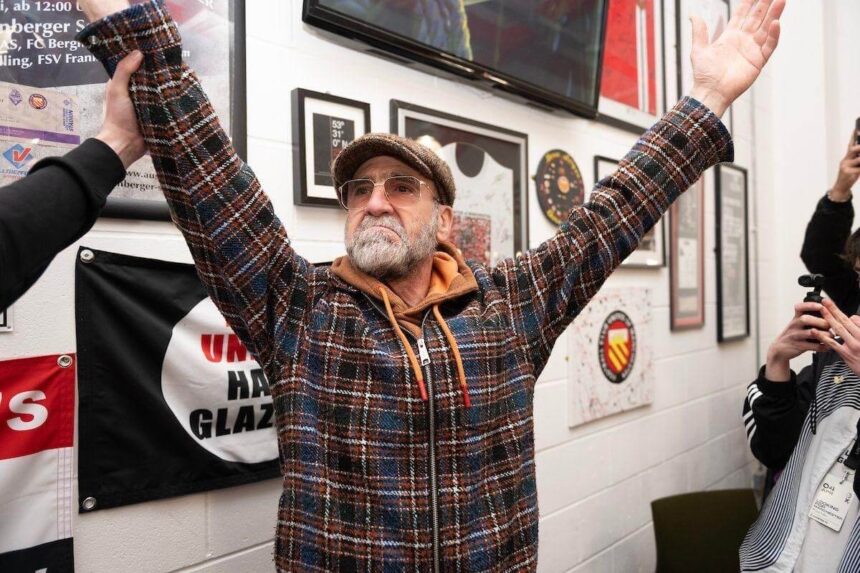

Eric Cantona has been a formidable spokesman, though, since the former United player visited FC recently and went public about the decline at the club where he played with such distinction.

Cantona spent four hours at Broadhurst Park, FC’s stadium in Moston, north Manchester, and thrilled his audience with his knowledge of the breakaway club, what they stood for and why it mattered to him, too.

Cantona meets FC United fans (FC United of Manchester/Looking FC)

He is now a signed-up member of a club that has been described by Kevin Miles, CEO of the Football Supporters’ Association, as having “totemic importance” for the fan-ownership movement. That club, says Cantona, have a “young history but a great history” — so great, in fact, that his two brothers and four children have signed up.

“I was totally wrong,” Gowling, a United player in the 1960s and 1970s, tells The Athletic. “I made a terrible mistake and I will have to take the embarrassment that comes with it for the rest of my life. They (FC) have surprised me. And full marks to them, I’m delighted they have continued a lot longer than I thought they would.”

We wish you a merry Christmas and a happy New Year

We’re FC United

We’re still f**king here!

Some people make the mistake of thinking that a breakaway club, nicknamed the Red Rebels, must be anti-United in some way.

The leaders of The 1958, United’s anti-Glazer protest group, visited recently for a ‘United United day’ and admitted they, too, had not been entirely sure what to expect.

Yet it doesn’t take long at Broadhurst Park to realise why a banner hangs inside this stadium with the message: “I Got Love Enough for Two”.

Inside the entrance, a framed Cantona shirt is signed by the Frenchman, with a dedication to “the new Theatre of Dreams”. Other pictures of Denis Law, George Best and various Old Trafford greats adorn the walls. A banner at the St Mary’s Road end pays tribute to the Munich air tragedy. Even the programme, FCUM Review, has a front cover designed like United’s.

Advertisement

But it is different here. “We are fighting for fan culture,” says chair Nick Boom. “More and more, that culture has been eroded. Supporters — the lifeblood of the sport — are being pushed further and further out. We think the experience should be all about the fans.”

Before the stadium opened in 2015, they used to know this place as the Ronald Johnson playing fields. Now there is a banner that reads: “No Glazers or Sheikhs by Ronald Johnson’s gates”.

This is a club where fans are invited to attend, or tune into, board meetings and every member receives a full report, via email, about what has been discussed (imagine that with the Glazers). Supporters can shape decisions based on a ‘one member, one vote’ system, whether it be choosing the kit, keeping admission fees affordable, electing board members or whatever else is on the agenda.

“FC United was created as an alternative for people who felt they could no longer go to Old Trafford, and to show that football clubs can be different,” says Paul Hurst, a board member and former United season-ticket holder. “Clubs can talk about ‘putting fans first’, but the only way to guarantee that is having a club that is 100 per cent owned by fans, where they have real, genuine power.”

In this part of Manchester, that means season-ticket prices for under-18s, working out at £1 per match, have not gone up in 20 years.

It is why, amid the sea of red, white and black banners positioned permanently in all four stands, one reads: “Making Friends not Millionaires”. Another carries the message, “Still Fans — No Longer Financial Supporters”.

It is why a mural on one wall reads “Our Club, Our Rules” and it is why you will never see any organisation’s name plastered across the front of FC’s pristine red shirts. Why the lack of shirt sponsors? Because that was part of the club’s stance from the beginning and, almost certainly, always will be.

When it comes to the ethos at FC United, the writing is on the wall (Daniel Taylor/The Athletic)

“It’s symbolic on our part,” says Boom. “We’d seen at United what can happen when a club becomes more interested in Singapore noodle partners than its actual fans. So we have chosen over the past 20 years not to have a shirt sponsor. It’s our two fingers up at this creeping culture of outright commercialism. And we’re proud of that.”

This is our club

Belongs to you and me

We are United – United FC

We may never go up

But we’ll never feel down

Now we’ve built our own ground

(To the tune of The Pogues’ Dirty Old Town)

Their first match was a friendly at Leigh RMI, 15 miles out of Manchester, on July 16, 2005, featuring zero goals, three streakers and a pitch invasion at the final whistle. The players, new heroes, were carried off shoulder-high.

Advertisement

These days, the club celebrate Gowling’s now-infamous quote by calling their Christmas party the ‘It’ll be all over by Christmas’ party.

At the start, however, nobody really knew what to expect when FC rented Gigg Lane, Bury’s stadium, and negotiated a place in the North West Counties League Division Two, the 10th tier of English football.

“It’s hard sometimes to believe we pulled it off,” says John-Paul O’Neill, the militant fan who came up with the idea and has written a book, Red Rebels, about this brave new world. “At the time, we just got on with it, even though we didn’t really know what we were doing.

“Securing a place in the North West Counties League inside three weeks was the big achievement, but that was just the beginning to getting a team on the pitch in time for pre-season.

“It was a crazy, crazy time. When 2,500 people turned up to the first game, it really was a fairytale. Most of the steering committee barely had time to think — I know I didn’t — so at the time we probably didn’t properly appreciate what we’d pulled off.

“Fans quickly started referring to that first season as a ‘summer of love’ and it did have that vibe to it. Everyone was on the same buzz, that the authorities over the years had steadily stripped from attending top-level football.”

The newbies of Manchester announced their presence with three successive promotions and eventually climbed as high as the sixth-tier National League (North). They set all sorts of attendance records in the process and, to quote the club’s website, “an unbelievable amount of fun was had at every game”.

Take the trip to Colwyn Bay, for example, when so many fans descended on the coastal Welsh town a large number had to watch the game from a farmer’s field on a hill beside the ground. There was the promotion game against Ramsbottom, when FC’s supporters chartered a steam train, christened ‘the Rammy Rattler’, to get them there on the East Lancashire Railway. Or the FA Cup tie against Rochdale, when a stoppage-time winner saw the fledgling side beat third-division opponents in front of a live television audience.

Now, approaching a milestone anniversary, FC have plateaued, 16th in the seventh-tier Northern Premier League. Their average attendance is just below 2,000 and, behind the scenes, they accept they have some way to go before they have fulfilled their potential.

But there is still plenty to like, including a sleek, 4,900-capacity stadium with facilities that are rented by Barrow as their own training ground.

Advertisement

Bradford City, another League Two club, decamped here when their pitches were covered in snow over winter. The facilities, in other words, are of a standard worthy of the English Football League (EFL). And, in true non-League fashion, there is a nice twist here that the club captain, Charlie Ennis, helped put everything in place. Ennis runs a building firm that has carried out work on the ground and helped to set up its gymnasium.

Having started with nothing but spirit and enthusiasm, the modern-day FC have a women’s team as well as under-21s, under-17s and academy sides.

Volunteers are essential at this level and the attitude is summed up by club photographer Lewis McKenna, who has covered more than 100 games at every level this season. In total, there are around 200 volunteers and, unlike many Premier League clubs (the two from Manchester included), ‘little United’ have never had an issue paying match-day staff the living wage.

Perhaps attitudes have shifted, too, since the years when Ferguson, championing the Glazers as “great owners”, made it clear he did not want to discuss, or accept, the presence of the breakaway club.

On May 18, an anniversary match will be held between a team of ‘FC Legends’ and one of ex-United players including David May, Wes Brown, Clayton Blackmore and Keith Gillespie.

Relations are good with Salford City, the League Two club run by Gary Neville, Ryan Giggs and Paul Scholes. The two clubs arranged a pre-season fixture last year. Another is pencilled in for this summer and, daft as it might sound, these are the sort of events that might have been much trickier, politically, a few years earlier.

“What Ferguson said about us was never true,” says Boom. “He made it sound like we had walked away and hated United, when it was never like that. All we are trying to do is give supporters a voice and show there is another way for football, where it is still fan-centric and we have our values.”

The supporters back their team loudly at each home game (Lewis McKenna/FCUM)

Ferguson had branded them as “sad” and “publicity seekers”. He held a grudge against the Manchester Evening News for printing FC’s match reports and, at the height of fan protests, he was a willing spokesman for United’s owners. When a group of fans challenged him about it, his message was “go and watch Chelsea”.

Advertisement

Yet it is widely documented that the most successful manager in British football had initially been against a takeover and met the fan leaders who were opposing it. He was asked if he would quit, or at least threaten to, but declined, citing the number of staff who depended on him — a line that, on reflection, seems ironic given the hundreds of people who have lost their employment under the Glazers and, latterly, the Jim Ratcliffe regime.

“If there’s one thing FC United will always be, it’s a mirror to Ferguson’s conscience,” says O’Neill. “The slightest indication from him that he’d quit if the takeover went through and the whole thing would have been dead in the water. He knows it and we know it. The Glazers are his legacy.”

His name is Malcolm Glazer, he thinks he’s rather flash

He tried to buy a football team but didn’t have the cash

He borrowed lots of money, he made the fans distraught

But we’re FC United and we won’t be f****** bought

So, how far can a club with FC’s beliefs and principles go? What is possible in a world that increasingly views football as the property of the super-rich?

“We want to progress as high as we can up the leagues and win trophies,“ says Hurst. “But that will never be at all costs, where we risk our financial sustainability or give up our core principles just to chase success on the pitch.”

Ideally, FC would like to be a league or two higher. In another 20 years, or even more, they would love to think Manchester could have a third representative among the 92 professional clubs.

This season, however, started with one win from eight games and FC were languishing in the bottom four until Mark Beesley, formerly of Warrington Town, was appointed as manager and has guided them to safety.

Equally, it was never going to be an entirely seamless process for a club that freely admits they were often ‘winging it’ during their formative years.

Advertisement

The most turbulent period in the club’s history attracted national headlines and culminated, in 2016, in the election of a new board and departure of general manager Andy Walsh, amid fierce criticism from factions of the fanbase about his leadership.

Others have questioned whether FC have sacrificed some of their old “punk football” rebelliousness, and the irony of the club racking up considerable debts to create and maintain their award-winning £6.3million stadium.

O’Neill, formerly editor of Red Issue fanzine, is a big part of FC’s story but no longer attends fixtures. “So tightly does the club now cling to establishment orthodoxy that, despite one of the founding principles being to ‘discriminate against none’, in 2021 they said they would introduce Covid passes if told to do so,” he says. “I’ve not been to a game since.”

It hasn’t always been straightforward, therefore, for a club described by fan and author Jonathan Allsopp in his forthcoming book, This Thing of Ours, as “imbued with the radical spirit of the city of Peterloo, Marx, Engels and the Suffragettes”.

Ultimately, though, the relevant people are entitled to regard the club’s 20th anniversary as a collective triumph.

“Over the last two decades, it’s been difficult to imagine a greater contrast between the owners of Manchester’s two red-shirted football clubs who bear the name ‘United’,” Allsopp writes. “One a club where supporters are bottom of the pile versus the other where supporters’ interests are its cornerstone.”

First-time visitors to Broadhurst Park are often struck by the colour and din, the originality of the songs and the general feeling that it is different at this level: real, earthy, unpretentious. And, yes, that really is 38-year-old Adam Le Fondre, once a renowned EFL and Premier League striker for Reading, playing up front.

Advertisement

“We’re helping to regenerate part of Manchester that’s been written off for too long,” says Boom. “It’s one of the most deprived wards in England and many families here are facing real financial hardship. But that doesn’t define them. There’s pride, resilience, and a strong sense of community — and we want to be a club that stands with people, not above them.”

Broadhurst Park doubles up as home to Moston Juniors. Relationships have been built with other local clubs, schools and community groups. It is important, says Boom, to be a “good neighbour” and that was never more evident than in the days after the Southport stabbings last summer.

Broadhurst Park is an impressive stadium, which opened in 2015 (Nathan Stirk/Getty Images)

When far-right protestors rioted outside a Holiday Inn in Newton Heath, a mile or so from FC’s stadium, a delegation from the club visited the hotel to offer support, friendship and free tickets to the asylum seekers it was housing.

These human touches matter in an era when many United fans have been left to feel, as Cantona says, that the Old Trafford club has lost its soul.

One story involves Tim Williams, a founder member of FC who was known as ‘Scarf’ because he had worn a red and white scarf, knitted by his mother, Betty, to every match he had attended since 1965.

Williams died last year and his scarf is now framed in the entrance to Broadhurst Park, donated to the club “to stop his family fighting over it”. A banner in the main stand remembers him another way. “Tim ‘Scarf’ Williams Stood Here”, it says.

All that is really missing, perhaps, is a wider choice of pubs within walking distance of the stadium. But it is not a big problem: FC have their own bar beneath one stand, decorated with scarves and flags and modelled on the kind of bierhaus you would find inside a German stadium.

The beer is cheap (well, a lot cheaper than Old Trafford) and a stage is set out before every match for local bands, comedians and poets — even a group of harpists — to perform. Hence the rather glorious scene on Easter Friday of a Mancunian punk band called Battery Farm belting out a song called Roy Keane is Not Real before a 3-2 home defeat to Whitby Town.

Advertisement

This weekend, when Guiseley are the visitors, board members will serve behind the bar in what has become a tradition at the last home match of the season.

And Gowling? No hard feelings, is the message from the top of the club. On the contrary, they would like to welcome the former centre-forward to a game one day.

“What Alan, and many others, probably underestimated was the resolve of those people involved in getting the club up and running,” says Hurst.

Russell Delaney was one of those people, despite being gravely ill with the lung disease sarcoidosis that eventually took his life. Delaney died in November 2005, aged 47, five months after FC’s formation. He is still talked about and his name lives on, attached to the club’s annual player-of-the-season awards.

“When you understand the love, care and dedication that went into forming the club, you realise there was no way the fans were going to let things just fizzle out after one season,” says Hurst. “Twenty years on, we’re still here and stronger than ever.”

(Top photo: Cantona surveys the surroundings of Broadhurst Park. FC United of Manchester)