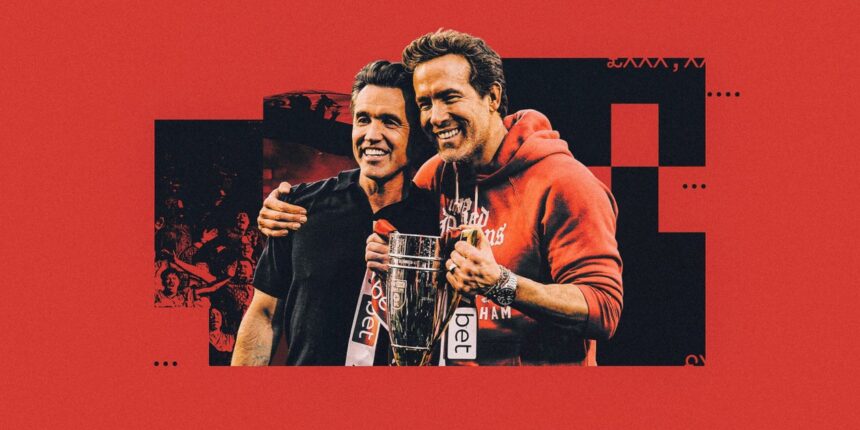

Four years, two months and 18 days after Ryan Reynolds and Rob McElhenney announced their purchase of Wrexham, the club sealed promotion for a third season running.

A 3-0 victory over Charlton lifted one of the world’s oldest clubs into England’s Championship, only one league below the Premier League. Not bad for a team who were in the fifth tier, the National League, back in February 2021, having dropped out of the EFL in 2008, the natural consequence of entering administration three seasons prior.

Advertisement

It marked the first time any club in English football history (yes, Wrexham are Welsh) had vaulted from the fifth tier to the second in three consecutive years, as well as the first triple-promotion in the top five tiers, full stop. And it was celebrated accordingly. As the final whistle blew, fans and flares dotted the pitch; in one patch of jubilation, club captain James McClean was hoisted aloft.

In the stands, Reynolds wept and McElhenney looked upon the sights before him in wide-eyed wonder. The win, the moment, marked another glorious success in a journey far from finished. One more promotion and they will play in the wealthiest football division on the planet.

If the story on the pitch has been loud and attention-grabbing, the one off it hasn’t been short of noise either. The club’s recently released 2023-24 financials, detailing the money behind their League Two promotion season a year ago, dropped jaws far and wide. Wrexham’s revenue last year hit £26.7million, a 154 per cent increase on their National League-winning year.

That is, to understate things quite a lot, not normal. Wrexham’s revenue last season set a fourth-tier record by a country mile; had the club been in League One, that level of income would have been the second-highest ever of any third tier club not in receipt of Premier League parachute payments, only (just) surpassed by Leeds United’s £27.4m in 2009-10.

What do Wrexham’s recent financials look like?

Despite the enormous income, Wrexham still posted a loss last season, though their £2.7million pre-tax deficit represented a 47 per cent reduction on 2022-23. The £16.2m increase in revenue comfortably outstripped a wage bill rise that, while up 59 per cent, only comprised a £4.1m increase in monetary terms.

Far more significant in limiting the bottom-line improvement was a sharp uptick in non-staff expenses, excluding fixed asset depreciation. Those expenses more than doubled to £16.1m, reflecting the cost of the club’s increased commercial activity, alongside general inflationary pressures. Viewed in isolation, these costs would appear ruinous for the average League Two or even League One club — and 10 Championship clubs recorded lower such expenditure last season — but Wrexham are currently far from average. The costs were key in driving those record revenue numbers.

Advertisement

In the years leading up to the takeover, pre-Covid, Wrexham’s financial performance generally hovered around break-even. The exception came in 2018-19, when a sell-on clause of around £1.25m on the back of former goalkeeper Danny Ward’s move from Liverpool to Leicester City pushed the club into profitability, but even that was only to the tune of £0.8m.

Covid depleted income and increased losses, though the real trigger for the latter was the arrival of Reynolds and McElhenney. In their first full year in charge, losses more than doubled. Then, a year later, they leapt higher still, as the National League promotion season brought with it a £5.1million loss — by far the biggest loss in the division that year and 85 per cent higher than next-worst Notts County (£2.8m).

To put last season’s £2.7million loss into context, only one League Two club, Newport County, booked a profit in 2023-24, and that was just £25,000. All of the remaining 20 clubs to have published last year’s financials (three are still to do so) posted a loss, and six of them booked a higher loss than Wrexham. Promotion cost Wrexham £0.8m by crystallising player bonuses and transfer fee add-ons; without those, their pre-tax result would have been better than two further teams. The worst financial result in the division came from Stockport County, who finished one spot ahead of Wrexham as League Two champions, incurring a £7.0m loss in the process.

How much have Reynolds and McElhenney put in and taken out?

Reynolds and McElhenney actually bought Wrexham in 2021 for a peppercorn (£1) from the supporters’ trust, though that did come on the proviso that they would inject at least £2million into the club. Within their first five months of ownership, they’d provided £2.2m in equity funding and, by the time promotion from the National League had been achieved, the duo’s direct funding of the club topped £12m. By that point, at the end of June 2023, Wrexham owed their owners £9.0m in interest-bearing loans.

As a result of the club’s increased income, the need for shareholder funding declined last season. £1.7m in 2023-24 was the lowest cash input in a season since the takeover. By the end of June 2024, total funding since the takeover sat at £14.1m, with £10.7m sat on Wrexham’s balance sheet as debt, incurring interest at three per cent over the Bank of England base rate (which was 5.25 per cent at that time).

Reynolds and McElhenney bought the entirety of Wrexham AFC Ltd from Wrexham Football Supporters’ Society Ltd via The R.R. McReynolds Company, LLC, a company they set up in the U.S. state of Delaware. The pair own 50 per cent each of R.R. McReynolds.

During the League Two season, they transferred all of their shares to a new holding company, Wrexham Holdings LLC, also based in Delaware. The latter appears to have been set up in anticipation of the duo selling minority stakes in the club.

Advertisement

That first such sale happened at some point between June 2023 and the end of March 2024, with R.R. McReynolds’ stake in Wrexham Holdings reducing to 95 per cent. That five per cent holding went to a U.S. consortium fronted by Al Tylis and Sam Porter, which had previously acquired around 50 per cent of Mexico’s Club Necaxa; at the time of the deal, Reynolds and McElhenney took up a reciprocal stake in Necaxa, and the two groups have since combined to buy Colombian side La Equidad.

This season saw more significant moves off the field. Another Delaware company, Red Dragon Ventures, LLC, was set up in September 2024 and has since bought up over 10 per cent of Wrexham Holdings — and so owns an equivalent stake in the club. Red Dragon Ventures is owned by R.R. McReynolds and Wrexham Scope LLC, with the latter owning a majority stake.

The 2024-25 season saw some significant changes in both the amount of owner funding Wrexham received and its source. Wrexham Scope is owned by the billionaire Allyn Family, who took a minority stake in the club in October 2024. In the same month, £11.3million in equity was raised by the club, and while the exact make-up of the source of those funds is unclear, later events are instructive.

Across the current League One season, a total of £28.7m in equity has been raised, with £15.0m of that going towards paying off loans due to R.R McReynolds. The remaining £13.7m has been used to fund operations, including an increased wage bill and heightened transfer fees, as well as to assist in the cost of building a new Kop Stand alongside other infrastructure improvements (£1m will be spent on a new pitch this summer). There’s likely now more cash to help this summer’s squad rebuild, too.

Wrexham are now free of shareholder debt, so their strengthened balance sheet can more favourably raise financing for any future projects. From Reynolds’ and McElhenney’s perspective, they have made back most if not all of the funding they’ve provided to date and are sitting on an asset worth several multiples its value of just four years ago (though that valuation currently still rests on the pair’s continued involvement). Future minority stake sales look likely. Per Wrexham’s Strategic Report: “Further partners would be considered, if they can add value and assist in the delivery of our objectives.”

Wrexham’s commercial income is bigger than five Premier League clubs

Wrexham haven’t skimped on spending to zoom their way up the English pyramid, but theirs isn’t a tale of rich benefactors just pouring money into the club, leaving a potential void when they eventually depart (or, as has often happened in English football, the well of the owners runs dry).

To say the club’s turnover has grown in the past four seasons is to understate the matter gravely. Wrexham’s income has soared since their takeover, to the point that comparing it with divisional rivals is futile. Last season’s £26.7m turnover wasn’t just a League Two record and wouldn’t just have been the second highest ever income for a non-parachute League One club, it was actually more than 11 clubs in the Championship, two divisions higher.

Income has picked up across the board since the takeover, with gate receipts and broadcast income each topping £3million, in itself impressive for a fourth-tier club. Yet it’s in the commercial sector where Wrexham have been launched into a new stratosphere since Reynolds and McElhenney arrived. Boosting commercial income has been a stated aim of football clubs for a little while now and Wrexham’s proportion of commercial revenue to total revenue was by far the highest in the country last season at 74 per cent.

Advertisement

Wrexham announced their commercial income as £13.2m when releasing the latest financials at the end of March, but impressive as that is, it rather undersold things. That sum didn’t include retail income or catering and stadium hire or commercial income made on matchdays, all elements we’d generally include for a true measure of a club’s commercial turnover.

Altogether, Wrexham’s commercial revenues in 2023-24 were £19.7m, a frankly enormous figure for a fourth-tier club. So enormous, in fact, that it outstripped five Premier League clubs, never mind those in the Championship and League One. Wrexham’s commercial income was the 19th highest in England last season, a statistic that underlines how impressively the club has been marketed and how successful the Welcome to Wrexham documentary has been.

In their own words, Wrexham actually make “no direct financial return” from the documentary. Instead, the exposure offered by Welcome to Wrexham is leveraged by the club to ink separate, lucrative commercial deals.

Those deals exploded during their first season back in the EFL, with commercial income up 213 per cent on 2022-23. The primary drivers were a front-of-shirt sponsorship deal with United Airlines, reportedly worth as much as £6million per season, and the stadium naming rights deal with Stok Cold Brew Coffee, also worth seven figures.

Other club sponsors now include HP, MetaQuest and Gatorade. Smaller related party deals with Betty Buzz — a premium sparkling soda brand owned by Blake Lively, Reynolds’ wife — and Four Walls — a whiskey brand owned by McElhenney and his fellow It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia stars — added just under £250,000 to the top line. Deals with advertising and advisory businesses headed by Reynolds added a further £1.1m.

Wrexham’s existing commercial deals expire at varying times, which is beneficial for a club surging up the leagues at a rate of knots. Promotion to the second tier offers heightened exposure in an American market Wrexham are already tapping to great effect, with next season marking the second year of CBS’ four-year broadcasting deal with the EFL. CBS airs at least 155 regular season Championship matches per year, significantly more than the minimum 38 games they agreed to show across League One and League Two.

Compared with Wrexham’s League Two season and their latest financials, broadcast income in 2025-26 will also be roughly £10m higher.

Advertisement

The past two pre-seasons have included tours to the U.S. and, to underscore the importance of foreign markets to Wrexham’s financials, 52 per cent of last season’s income was generated outside of Europe. That’s an unheard of ratio, one rooted in the fact Wrexham currently appeal very differently to your usual team. As The Athletic’s Felipe Cardenas said on a recent The Athletic FC podcast: “In the U.S, Wrexham is a celebrity brand, not a football club — yet”.

To get an idea of just how unique the marketing of Wrexham is, consider that United, the front-of-shirt sponsor, debuted Wrexham-themed pyjamas in their premium cabins on a select number of long-haul international flights last summer.

Despite all that, Wrexham’s commercial income hasn’t jumped up in 2024-25 and potentially won’t next year either. Their sponsorship deals are heavily linked to the documentary and the ability to showcase partners there; playing in a better league will help, but up to now, sponsors have been more bothered about the exposure Welcome to Wrexham brings.

That exposure has been an obvious boon for the club, though there’s a cost to it. Those £16.1m in non-staff expenses mentioned earlier included £5.9m via related party companies, including £2.4m in Welcome to Wrexham promotional costs owed to Wrexham Holdings LLC. Maximum Effort and MNTM, advisory and advertising businesses run by Ryan Reynolds, incurred £2.1m in costs last season, though there was that £1.1m in income coming the other way. Similarly, McElhenney’s More Better Industries production company cost the club £1.2m in 2023-24.

Wrexham’s Strategic Report in the latest accounts was clear to highlight that while such arrangements will “remain in place while we are achieving the best financial outcome” for the club, they were also “consistent with those that would be made to other agencies who could offer similar services”. In other words, the club is paying the market rate.

The manner in which Wrexham’s commercial income has evolved is built on more solid foundations than many may realise. Were the club simply coining money in directly from the documentary, that would leave them open to a sharp drop-off once it eventually ceases being commissioned. Instead, through agreeing separate deals, the club has partly insured itself against when that day comes. Ensuring the costs of getting those deals are market-linked serves to keep the club’s finances away from the land of fantasy.

Of course, were Welcome to Wrexham to cease filming tomorrow, sponsors might rightly think twice about renewing at their existing rate. But through building the club’s brand, Wrexham are working towards mitigating the inevitable reduction in interest that would follow should Reynolds and McElhenney ever take their leave of North Wales.

Advertisement

What are they paying players?

The wage bill at SToK Cae Ras leapt again last season, as it has in each season under new ownership. At £11.0million, Wrexham’s wage bill was £7.1m (182 per cent) higher than just two years earlier. It will only have risen further since.

Wages are generally deemed the best financial barometer of where a club will finish in a given league season and Wrexham have adhered to the theory. Of the 11 League Two clubs to release wage data for last season, Wrexham’s £11.0m was the highest, over £3m higher than the next biggest spenders, Forest Green Rovers. The latter very much didn’t adhere; they finished bottom of the table and were relegated.

Stockport didn’t publish wage figures and their hefty loss suggests a strong likelihood their figure was up with — or even beyond — Wrexham’s. Yet it’s still clear Wrexham were handsome payers in League Two and that £11.0m figure is the highest fourth-tier wage bill ever disclosed. It would also have been the seventh highest wage bill in League One last year.

Still, the evolution in Wrexham’s turnover has outstripped their wage costs and did so substantially last year.

Wrexham’s wages-to-turnover ratio in their League Two promotion season was just 41 per cent, down 25 per cent on a year earlier. What’s more, of the 71 clubs in England’s top four tiers to release wages to turnover figures, Wrexham’s was the lowest in the country.

On a cash-flow basis, Wrexham’s wages control — or, at least, the pace by which revenue outpaced wage growth — was such that they were cash-positive at the operating level, to the tune of £2.5million. That might not sound like much, but of the 46 EFL teams to publish a cash flow statement for 2023-24, only five posted positive operating cash flow. What’s more, Wrexham’s figure was the best of the bunch.

How does their transfer spending compare?

Even before the 2021 takeover was officially done, Reynolds and McElhenney donated money to cover deals in the January transfer window, namely in the forms of Dior Angus, signed from Barrow, and Tyler French, who joined from Bradford City.

Advertisement

Neither Angus nor French play for Wrexham anymore, both moving on even before EFL status was reclaimed. In all, 59 different players have joined the club since February 2021, which equates to buying over half a new team every transfer window.

Such is life in the lower leagues that most of those players joined for no fee, but there have been a number of notable exceptions. Sam Smith’s arrival from Reading in January for £2million smashed the club record for highest fee spent, which was set four months earlier when Mo Faal joined from West Brom for £590,000. The current League One season has been notable for its increased deployment of transfer spending. Before it, the biggest transfer made was the £300,000 signing of Ollie Palmer from AFC Wimbledon in January 2022, a transfer that broke the club’s transfer record for the first time in 44 years, surpassing the £210,000 spent on getting Joey Jones back from Liverpool in 1978 (equivalent to £1.1m today).

Wrexham’s previous activity still put them at the top end of transfer spenders in League Two and the National League. At the end of last season, Wrexham’s squad had been compiled for a total cost of £3.1m, the highest amount in League Two and only behind three League One clubs.

Wrexham’s accounts didn’t disclose the amount spent in 2024-25, but the signings of Smith and Faal, alongside fees spent on Ryan Longman, Ollie Rathbone, Seb Revan and Dan Scarr, will ensure their squad was one of the most expensive in the third tier this season. It seems a decent bet that Wrexham’s squad cost ranking mirrored their league position: second, behind the even-bigger-spending, Tom Brady-backed Birmingham City.

Alongside the higher wages those signings will have inevitably brought, Wrexham will also see the fees flow through to their bottom line in the form of player amortisation costs. Their £964,000 in League Two last season was already a divisional record (reflecting the lack of transfer spending in England’s fourth tier), and with the League One high last year being just £1.2m at Peterborough United, its again clear Wrexham (and Birmingham) will have been right at the top this term.

How much can Wrexham spend this summer?

Wrexham will now enter their fourth consecutive season of having different profit and sustainability rules (PSR) to abide by. In the National League, there were no rules; in League Two, they were required to keep salary costs to 50 per cent of turnover; in League One, that jumped to 60 per cent; and in the Championship, soft salary caps are done away with and clubs are instead limited in the amount of money they can lose, after deductions for allowable expenditure.

Financial rules over the past two seasons have caused little in the way of impediments because they allow equity injections from shareholders in their calculations, meaning if an owner is willing to provide funds they don’t ever want back, clubs can spend as much of it as they please.

Advertisement

If regulation has been light touch to date, it will harden next season. The Championship’s PSR rules focus on limiting losses (much like the Premier League’s), with clubs playing in the EFL only permitted to book up to £13million a season in PSR losses. In 2025-26, Wrexham will have, plainly, spent the current and previous two seasons in the EFL, so they’ll be limited to £39m in PSR losses across the last three seasons.

Even that isn’t quite the full story. Those PSR losses are calculated after removing allowable expenditure on youth development, community development and women’s football, alongside depreciation and non-player amortisation costs, but the state of the UK economy in recent years also compelled the EFL to go a bit further. In 2024-25, clubs can adjust their PSR calculation for a ‘Cost of Living allowance’ of £2.5m, which will rise to £3.5m for next season and beyond.

Wrexham, alongside their fellow 2025-26 Championship clubs, will effectively be able to lose £45m across the 2024 to 2026 PSR cycle, after the standard deductions for allowable expenditure.

Wrexham’s 2023-24 loss of £2.7m will be included in next season’s PSR calculation, but even if this season’s loss in League One was double that of a year earlier, we estimate Wrexham could lose £34m in the Championship next season and still remain PSR compliant.

In buying back their home stadium in June 2022, the Racecourse Ground, now known as the SToK Cae Ras, and undertaking various improvements, Wrexham spent £10.9m on infrastructure in their first three full seasons under new ownership. That’s more than triple their cash spend on transfers in that time and the fifth highest spend of that kind among clubs that didn’t play in the Premier League in that time.

Still ongoing is the matter of a stadium lease held by the Wrexham Supporters Trust (WST). WST previously leased the ground from its old owners, then sub-leased it to the football club; now, though the club own the ground, the lease remains in place.

WST members voted last year in favour of surrendering it, but the Trust will only do so if certain protections to ensure the stadium remains an asset working in the best interests of the club are met. Wrexham’s current plans for the ground involve grant funding, which comes with its own conditions, in turn complicating their ability to sign up to the protections wanted by WST. The expectation is that matters will be worked through and the club will, eventually, assume full control of the ground, but they aren’t there yet.

Advertisement

Wrexham have big plans for the future, particularly if the ultimate goal of reaching the top tier is achieved. The building of a Kop Stand, slated to open in time for the 2026-27 season, will commence this summer even as the lease issue remains in play, but removing the latter barrier is paramount to future ambitions — as is how soon they can reach the Premier League.

What’s next?

Wrexham’s rise has been accompanied, almost unfailingly, by suggestions that they will not be able to maintain it.

As clubs progress, the standard of opposition improves — there is a reason no one has ever enjoyed the trio of promotions Wrexham have.

Yet there’s also a reason Wrexham have broken such records. They have been well-funded, yet they’ve also been able to turn newfound attention into big income, which was then used to buy experienced professionals and pay them wages no other lower league clubs could. Across their National League and League Two seasons, they invested in players who, frankly, were much too good for the divisions they were in.

This season’s promotion from League One has been more impressive. Again, Wrexham have spent money, with their transfer spend going up noticeably. Yet League One as a whole spent £43million on transfers this season, and while Birmingham City accounted for a majority of that, it’s not like Wrexham were able to just outspend everyone else.

As well as shifting to increased transfer spending, Wrexham’s profile of signings has moved, too. Jay Rodriguez’s arrival from Burnley in January aged 35 looked akin to the old strategy, but several of this season’s recruits have been at the start of their careers. Faal and Revan joined aged 21, while goalkeeper Arthur Okonkwo and defender Lewis Brunt were little older. Meanwhile S,mith, Longman and Rathbone all represent signings in their peak years.

Hard-nosed decisions have been made about some of the older heads. Paul Mullin, one of Welcome to Wrexham’s stars, and Ollie Palmer, himself a regular presence on screens over the course of the documentary, had jointly scored 154 Wrexham goals since joining in the 2021-22 season. Following the signings of Smith and Rodriguez in January, neither Mullin nor Palmer has played a single league minute for the club.

Advertisement

A significant squad overhaul awaits this summer and, in truth, it will dictate the pace of their next stage of progress. On a financial basis, there’s little reason to suggest Wrexham can’t compete with Championship clubs. The club’s commercial income is gigantic and while growth won’t mirror the huge National League to League Two increase, it already trails only three Championship clubs. One of those, Leeds United, has now been promoted.

The pace of Wrexham’s ascent has given rise to other challenges faster than the owners may have expected.

Wrexham’s training facilities have long been rented, usually in the form of the Welsh Football Association’s Colliers Park, with players getting changed at SToK Cae Ras before driving three miles to the training ground.

The club’s youth facilities now lag behind peers. Wrexham achieved Category 3 status for their academy at the beginning of this season, but many Championship clubs already have Category 1 setups. This is all without going into the obvious limitations of the SToK Cae Ras and its low capacity (currently 12,600), even when the new Kop Stand is finished in a year’s time.

The finances of the Championship are on a higher plane, too. Last season’s average wage bill in the second tier was £37.2million. Even if we strip out the five clubs in receipt of parachute payments (for clubs recently relegated from the Premier League) in 2023-24, the average still sits at £28.2m, reflecting the significant cost of even just competing for the Championship play-offs. On a squad cost basis, again removing those parachute clubs, the average last season was £19.2m. Wrexham have started spending more on fees, but they’re now joining a league where clubs have much more expensively assembled squads. They also have a number of well-paid older players they’ll need to move on.

Having said all that, Wrexham arrive in the second tier with both momentum and opportunity. Ipswich have been relegated back to the Championship for next season, but their jump from League One promotion to the Premier League through 2023-24 showed what well-funded clubs from the lower leagues can do.

With both Birmingham City and Wrexham on their way up in possession of strong backing and, certainly in Wrexham’s case, impressive revenues, the chances of the promoted sides competing at the top end are heightened. Wrexham’s income outstripped 11 Championship clubs when they were two leagues below them. Now, with higher broadcast income, there’s a strong chance they’ll be the highest-earning non-parachute club in the Championship next season.

A fourth successive promotion would be an astonishing achievement by any measure. It isn’t probable, but it’s far from impossible.

(Top photo: Kya Banasko/Getty Images; design: Eamonn Dalton/The Athletic)